FOREVER YOUNG

KEVIN CAMERON

GARY NIXON NEVER RETIRED, AND HE'S NOT FADING AWAY

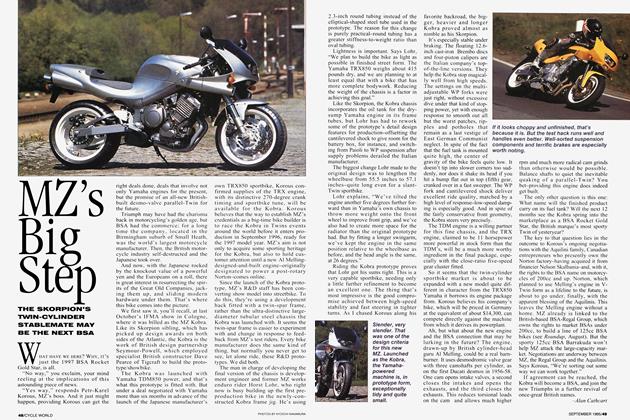

ITURNED THE CORNER AT THE END OF THE GARAGE AND there was Gary Nixon, in a lawnchair as always, surrounded by bikes and activity. Nixon is 51 years old and looks entirely himself-no thicker or thinner than in his factory racer days, his hair and deeply creased face as distinctive as ever. He rose to greet me.

Behind Nixon were the many classic racebikes of Team Obsolete, the creation of lawyer and all-around controversial large person Robert Iannucci. There’s a 500cc Manx Norton, two Matchless G50s, an AJS 7R, a BSA Rocket 3, all on fresh tires, many built from recently made parts supplied from the world’s amazing classic-racing infrastructure. Need a Manx cambox complete? A firm in England will supply it in the original green-finished magnesium, at just under $4000. Iannucci himself is a man who inspires strong feelings. Loyalists propose that he has single-handedly put classic racing on the U.S. motorsports map. Others paint him as a self-centered empire-builder. Both groups know he is highly intelligent and energetic, infuriating perhaps, but good company all the same. I asked Nixon how things were going. “I wish Erv was here,” he said through almost-closed teeth, his lips hardly moving. “Erv” is Erv Kanemoto, Nixon’s tuner for most of the 1970s.

This is to be a weekend of vintage racing for Gary Nixon, Team Obsolete and Robert Iannucci here at New Hampshire International Speedway. In the years before this track replaced the old 10-turn Loudon circuit, Nixon won nationals here on four different brands-Triumph (1967, 1970), Yamaha (1973, 1978), Kawasaki (1973) and Suzuki (1974).

Indeed, this is the weekend of the AMA national as well as the American Historic Racing Motorcycle Association (AHRMA) national; in the pits are lined up the tractor-trailer rigs of the major factory teams, and the shriek of inlineFours fills the air.

There are other familiar faces here. Talking with Nixon and his college-age daughters is David Aldana, who will ride the Team Obsolete BSA. Aldana won his first roadrace national, at Talladega in 1970, at the age of 19 on just such a factory Triple. Busy with details on the 7R is permanent racer and globe-trotter David Roper, who now has an incredible number of hours on single-cylinder machines. Roper is a very talented rider in his own right, not just among vintage riders. He simply enjoys racing-of whatever sort. While Iannucci might like to expunge twostrokes from his version of history, Roper has a Kawasaki AIR that he rides for pleasure. The two men agree to disagree for their mutual benefit and amusement.

And maybe Iannucci isn’t as historically doctrinaire as he is billed. On the workbench I see a tube of Yamabond case sealer. A hard-liner would surely use only Hylomar.

Why is Nixon here? Has he been drawn back by the promise of castor-oil fumes, vibration and the opportunity to relive a halcyon past? Will we hear him fondly recount tales of races won on carefully crafted old-world machines whose like we’ll never see again? No. Nixon is here because he is being paid to be here. That’s how racing works among professionals. Nixon is professional to the core.

Racing hasn’t been all positive cash-flow for Gary Nixon. Unlike today’s roadrace stars, he had no manager, cutting deals and investing wisely in condos and tax-free bonds. When Nixon began racing, wealth meant having enough money to keep the bike running and get to the next race. As it is, he says he has enough money “to about last me, if I’m careful.” Gary Nixon Enterprises, a racing-supplies business he ran for years, has now been supplanted by a radio-controlled-model store. Nixon gets by.

“I think I still got some Mikuni slides and needle jets-all the things that cost too much for anyone to buy-somewheres,” he remarks, grinning suddenly, revealing his large white teeth.

Practice goes poorly, and Nixon is preoccupied by it. Racing is like that. The number-one Matchless, the one descended from the work of legendary practical engineer Albert Gunter, won’t start. No compression. Nixon gets stiffly off, just as I recall his doing from countless Kawasaki H2Rs, and returns to slump in the lawnchair. Somehow, the camdrive on the big Single has slipped. Iannucci is disgusted, issuing commands to his retainers. In time, the machine is put right, but with much head-shaking. It’s hard to get a machine built as a racebike should be built without the solid foundation of a permanent ridertuner relationship.

That’s what Nixon had with the equally legendary Erv Kanemoto, with whom he had a 50/50 partnership, win or lose, from 1973 to ship, or 1978. Together they built an incredible string of wins, nearly including the 1976 World Formula 750 title. That one was politicked out from under them by peculating race officials in Venezuela.

The G50 is ready again. It starts this time, and Nixon rides out to practice. Shortly, he’s back. The engine has seized. There are days like this. At Atlanta in 1973, Nixon went through engine after engine-one nearly cut itself in half-on the factory Kawasaki H2R. Kanemoto, using an upturned gas drum as a workbench, tried to keep up. Then they came back to win three nationals in a row.

This time it’s the G50’s scavenge oil pump, which has somehow got a chunk of aluminum in its teeth. The engine comes apart again and Nixon is given a Team Obsolete customer bike, a 1992 model. The G50 was built from 1958 to 1962, but so popular are the bikes for today’s vintage-racing scene that entire new bikes can now be ordered, built from modern reproduction and substitute parts. The price is about $45,000, or what you might pay for a nicely restored original machine.

The failures at Loudon are a break in Team Obsolete’s usually high equipment reliability. Roper, on Iannucci’s Singles, has won countless races at prestigious invitational vintage meetings all over the world. But there are days at the track when nothing goes right.

Nixon comes back in from practice, growling, half amused, half concerned: “I got a 12-lap race to ride and my wrist is giving up after eight!” He sat in the lawnchair, examining the wrist and planning out loud how to deal with it. Nixon builds sentences like a hyperactive bricklayer working on three walls. He spits out a few words on one subject, switches to another, returns to drop another couple of explanatory adjectives on the first sentence, then starts another. There may be long pauses, but all the subjects remain open. Later, he stalks off to find the medical service, and returns with a wrist brace.

“I was having to...” He forms his left hand into a hook, showing how he pulled the clutch with his arm instead of his fingers. Such physical disabilities preoccupy him; he holds up the arm, looks ruefully at it, and grins, saying, “I gotta do a few exercises.” At Daytona in 1976, when a hard practice left him breathless, he had said, “I gotta get in shape,” and started jogging down pit lane. Then he’d stopped, wheezing, and called for his cigarettes. Exercise did not make Gary Nixon a national winner; strength of character and determination did that.

Whenever describing a tough situation, Nixon makes a characteristic face, pulling his mouth out wide with his cheek muscles in a kind of wince, with a sharp intake of breath through the teeth. Both he and Erv Kanemoto make this face. Which is the original? Probably, like everything else in their 1970s racing program, it was 50/50. Today, he makes this face when I ask him if he’s enjoying this kind of racing, whether he’ll do more of it in future.

Nixon motioned towards the Matchless, which besides its engine maladies, had managed to leak a fair amount of its vital fluids. “Rode that one, the ‘hot’ one (he says this with an upward flick of the eyebrows) and stuff come out the side. Stuff come out the bottom. 1 don’t know where it’s gonna come out next. I don’t think very many people want to pay money to come see me wobble around in last place.” Nixon fans remember this brand of painful honesty: “Gary, how come you didn’t win that last one, man?” someone would ask. “Them other guys rode faster’n me,” he would answer.

IXON MISSED THE BIG MONEY. WHEN HE BEGAN RACING, WEALTH MEANT HAVING ENOUGH MONEY TO KEEP THE BIKE RUNNING AND GET TO THE NEXT RACE.

Nixon’s two daughters push him around in gentle, familial ways, grabbing his last french fries, bantering, making off with the van to get supplies. He’s a lucky man to have such company, and he knows it.

Meanwhile, it’s time for Thursday’s AHRMA vintagebike program. Races are running, and we all walked out along pit road to watch. A race countdown is at one minute when Aldana said, “Excuse me, I gotta see this.” I stand aside as he looks with interest at the starter’s technique with l-minute board and flag. “Okay, he gives it the slow turn. I know when I’m goin’!” Aldana remarked. Dirttrackers pay close attention to starts.

Aldana’s race is next up, and he is far back on the grid. When the flag drops, two men are away a close l-2; local star Todd Henning from row one, and Aldana carving through from nowhere. It would be this way all weekend: Nixon and Aldana, the veteran dirt-trackers, consistently got rocket starts.

Aldana has his share of the weekend’s bad luck, though. The five-speed gearbox in his Rocket 3 breaks a shift fork. As a Team Obsolete mechanic pulls the beefy internals out into a tray, Aldana starts telling BSA stories. He gets halfway into a second funny one when he stops, saying simply, “Aaagh, BSAs!”

That dismissive gesture defines a distance between vintage machines and the men who rode them. The machines are mute, and anyone can appoint himself their spokesman. Whether for the simple pleasure of ownership, or for financial speculation, the message is nostalgia. On the other hand, the heroes who rode these bikes know too much. Real life is real life whenever it was lived. For every intense moment in Turn Three or at the checkered flag, there was a balancing negative-for instance, to see the hot kid of the week get the smiles and good stuff from factory bosses, while an honored veteran gets hooked-over sprockets and a tired engine. Racing is a lot like life that way.

Gary Nixon never gave up racing. Every time his racing career appeared to be over-whether from injury, factory unfashionability or personal matters-he would emerge as strong as ever, still winning races. When people would ask about his latest comeback, he’d reply, “What comeback? I was never away.”

Any attempt to talk to this man about the nuts and bolts of racing is met with bland disclaimers: “I don’t know...never thought about it much.” In 1976, at the original Loudon racetrack, he astonished everyone along pit lane by braking so powerfully for Tum 10 that his back wheel hovered 3 inches off the pavement all the way in, every lap, smoothly and predictably. Today, this is normal for riders in a great hurry; in 1976, no one had ever done it before.

“I never knew that was even happening...’til someone showed me a photograph,” was all Nixon had to say about it.

Nixon was once invited to teach a racing school. “What would I tell ‘em?” he asked. “Watch the starter, try to get a good start, then when the race kinda settles in, bike’s runnin’ halfway decent, start lappin’ guys, and if everything goes right, you win the race.”

Nothing to it. If you watched his riding closely, you’d never see him take the same line twice. “Them other guys, ridin’ that ‘Hailwood’ line (again the special emphasis, the slightly mocking lift of eyebrows), you could get their attention pretty good if you come up the inside, lookin’ like you’re not gonna make it.” That was the essence of the “inside stuff,” the Nixon maneuver that pushed classicists off their wide line, then left them behind.

By 1977, Nixon and Kanemoto had left the Kawasaki camp and were re-equipped with the next-generation 750-the four-cylinder Yamaha TZ. Results escaped them with this bike. Each man went through a torment of self-examination, sure he alone was to blame. The bike was blindingly fast, but there were always problems-detonation, a bad day, a swelled O-ring. To keep the operation going, Kanemoto prepared bikes for younger riders; at first Randy Mamola, then for a young, fast Louisianian named Freddie Spencer. Nixon’s bike was always ready for him every race, but after a while, the Nixon/Kanemoto partnership went onto a mutually agreed hold.

Fifteen years later, Nixon, frowning, stood in the Loudon garage and looked out. “I wish Erv was here,” he said again. It’s a cruel fact of racing that tuners’ careers continue after riders must turn to other things. The relationship of rider and tuner can be very close, with the mere presence of the tuner coming to stand for reliability, security, good handling, good times.

With that kind of support, it’s easier to trust that the front tire will take the hard flick-in, lap after lap. For the tuner, a rider like Nixon, who genuinely gives all he can, is his only professional means of self-expression. When that relationship ends, it leaves a big emptiness on both sides. Nixon and Kanemoto are still close. Spencer and Kanemoto still spend time on the telephone. By saying, “I wish Erv was here,” Nixon was saying, “I wish everything was all right. I wish I was having a better time.”

Motorcycle-racing enthusiasts who saw the contests of the late 1960s and 1970s remember starting grids full of

strong characters like Nixon and Aldana-three-dimensional people with strong and evident likes and dislikes. Some say they find today’s riders somehow lacking in these dimensions. This sounds like sour-grapes nonsense, like oldtimers saying, “They don’t make ’em like they used to.” Of course, today’s riders all have personalities; it’s just that under today’s conditions, they can’t afford to play them at full volume.

EVERY TIME HIS RACING CAREER APPEARED TO BE OVER, NIXON WOULD EMERGE AS STRONG AS EVER, STILL WINNING RACES.

Today’s top riders are paid big money, and they know that this money paid makes them representatives of The Company. They are ambassadors of good clean fun and family values. To qualify for big money, they must not only perform well in races, but they must perform elsewhere in corporate-approved fashion. This is simply today’s Yuppie contract, translated into racing terms. Give up your own personality in these listed respects, and assume instead our prosthetic personality-and we’ll give you the money.

Gary Nixon missed the big money, but he had, and still has, his liberty. His exercise of freedom and independence-standing up to officials, speaking honestly and directly, and continuing to win international races long after factory team managers had dismissed him as history-these are the reasons we love him. We’d all like to be able to afford that kind of freedom.

Saturday at 12:45 was the hour scheduled for the grandly named Two-Wheel Greats Showdown, run as an appetizer to the AMA program, in which it was “hoped” out loud that the riders invited would create at least the appearance of a contest.

In the end, no one was pleased. The first displeasure is that vintage racing is not well-accepted by the AMA. The AMA is streamlining itself for television, while vintage racing hails itself as “the fastest-growing branch of motorsport.” Both AMA and AHRMA need more space in the program, but there is neither room nor official tolerance for both. Anyone who saw the vast vintage pits at Daytona knows that vintage activities can no longer fit into one day. At Loudon, what formerly were several Sunday vintage events have been shrunk into five laps on Saturday. The final discontent was that while some of the two-wheeled greats produced the hoped-for contest, others streaked out ahead as racers will.

Never mind. It was great to see Gary Nixon at a national, neither reduced nor magnified by time’s passage. After the racing, a plan was proposed to put Nixon back on the 750 Kawasaki he had ridden in late 1976. The machine now belongs to a collector who would love to have the great man ride it again. Would Nixon be willing to consider it?

Yes, he would. On a professional basis, of course. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontLetter To Willie G.

November 1992 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Bicycle Connection

November 1992 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCUnseen Drama

November 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1992 -

Roundup

RoundupFirst Look: Kawasaki 1993

November 1992 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupWorld's Fastest Refrigerator

November 1992