THE NATURAL

Life and times of the Motorcycle Prince

JON F. THOMPSON

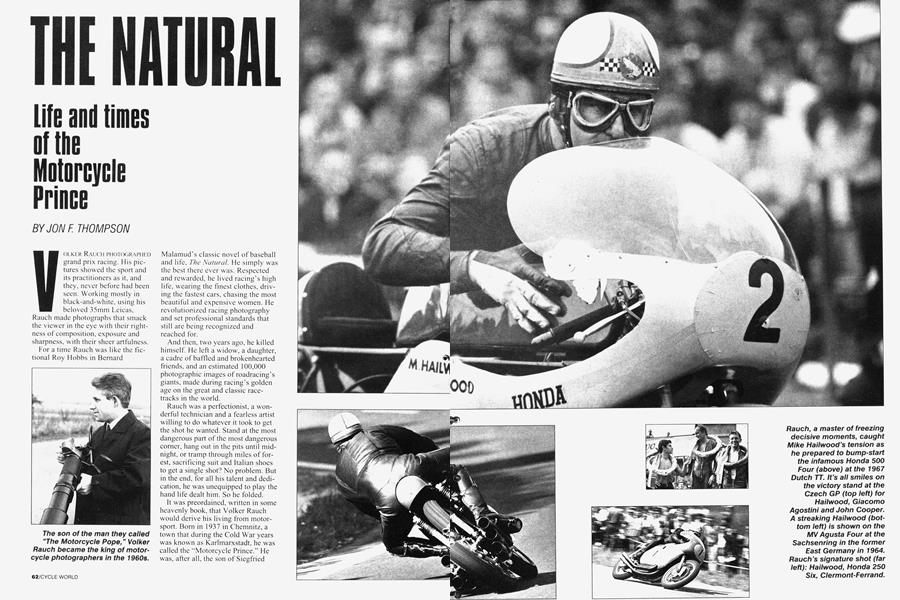

VOLKER RAUCH PHOTOGRAPHED grand prix racing. His pictures showed the sport and its practitioners as it, and they, never before had been seen. Working mostly in black-and-white, using his beloved 35mm Leicas,

Rauch made photographs that smack the viewer in the eye with their rightness of composition, exposure and sharpness, with their sheer artfulness.

For a time Rauch was like the fictional Roy Hobbs in Bernard Malamud’s classic novel of baseball and life, The Natural. He simply was the best there ever was. Respected and rewarded, he lived racing’s high life, wearing the finest clothes, driving the fastest cars, chasing the most beautiful and expensive women. He revolutionized racing photography and set professional standards that still are being recognized and reached for.

And then, two years ago, he killed himself. He left a widow, a daughter, a cadre of baffled and brokenhearted friends, and an estimated 100,000 photographic images of roadracing’s giants, made during racing’s golden age on the great and classic racetracks in the world.

Rauch was a perfectionist, a wonderful technician and a fearless artist willing to do whatever it took to get the shot he wanted. Stand at the most dangerous part of the most dangerous corner, hang out in the pits until midnight, or tramp through miles of forest, sacrificing suit and Italian shoes to get a single shot? No problem. But in the end, for all his talent and dedication, he was unequipped to play the hand life dealt him. So he folded.

It was preordained, written in some heavenly book, that Volker Rauch would derive his living from motorsport. Born in 1937 in Chemnitz, a town that during the Cold War years was known as Karlmarxstadt, he was called the “Motorcycle Prince.” He was, after all, the son of Siegfried Rauch, a leading expert on two-stroke engines and the man they called the “Motorcycle Pope.”

But if there w as premix pumping through Volker’s veins, there also was photographic developer and fixer. And leavening those components w as the journalist’s inexplicable desire to witness something and tell the world about it.

Using a battered old Pentax, he began taking racing photos as a teenager at small tracks around the former East Germany. When Siegfried obtained permission to travel into West Germany for the 1955 running of the German Grand Prix at Hockenheim, he obtained permission to take Volker with him. Once in West Germany, the pair simply decided to not return to the dreary, gray Communist life. And if it was remarkable that East German officials allowed the Rauchs to travel to West Germany in the first place, there was something even more remarkable: Following the Rauchs’ defection. East German officials allowed the rest of the Rauchs to move to West Germany as well. The family settled in Nürnberg, and that's where Volker stayed.

“This was very strange and unbelievable,” says Hildegard Rauch, Volker’s widow, now remarried and living near Munich. “Siegfried was a genius in his branch (of work), and nobody could understand that they didn’t force him to come back. They tried to use him as a spy, I think, but he didn't have any dark sides to his biography, so they couldn’t (blackmail) him.”

What happened next was the critical element in Volker's rise to photographic greatness. He obtained w hat w as at the time one of the world’s leading forums for his work.

His father became editor-in-chief of Das Motorrad, then, as now, Germany’s leading motorcycle magazine.

Hildegard remembers, “And then Siegfried brought up Das Motorrad to a circulation of nearly 300,000 every 14 days. This only could take place because Volker was taking pictures and reporting on the grands prix and other sport. It was like other people play piano or dance. He had this special talent. And he was very confident. He laughed and said, ‘I know I am the best.'”

Volker’s genius w>as so evident that it caught the attention of Leica officials. They sponsored shows of his work. They enlisted him as a field tester, and they loaded him down with their latest equipment.

Volker Rauch was now secure in his career and set to do some of his best work. Magazine editors from all over the world came knocking at his door. One of the seekers was Joe Parkhurst, Cycle World's founding editor and publisher.

“He was a superb photographer, he went to all the races, and he had a very sophisticated point of view,” recalls Parkhurst. He adds, “He was a celebrity in Europe. Nobody was doing his quality of work. I needed someone like Volker who really knew what was going on to make our title. Cycle World, w'ork out. He was truly invaluable to us. He was a real artist, and he had that devoted singlemindedness that creative people have. His photo of Hailwood on the Six-that famous rear three-quarter that we published and made into a poster-that’s a sample of his determination. He'd found a place on the course, it was the French GP at Clermont-Ferrand, where he could see what Hailwood was doing with that bike. He framed it and he got it razorsharp. Volker always got that allimportant point-of-view, the right place on the track, the proper framing. There are always a few places where something’s going to happen and where the light would be just right, and Volker knew where they were.”

And yet Rauch’s genius went beyond that, Parkhurst recalls: “We’d stand side-by-side and shoot the same thing. Later I’d look at both our shots and wonder, gee. were we really in the same place?”

Parkhurst also knew I lildegard Rauch, whose parents ran the lab in Nürnberg where Volker processed his film. “She was very pretty and provocative and I found her attractive,” he now recalls, smiling. And he adds, “Hildegard was a very sweet and sincere woman, and a good companion for Volker. I think Volker liked the influence that good women have on marriages, when the man allows it. They seemed to have a lot of compatibility. They thought a great deal alike, and they seemed to have a lot of fun together.”

Eventually, Rauch was selling his work not only to Cycle World and Das Motorrad, but also to lots of other publishing and corporate clients. The money began flowing in. Good times, good food, fine clothes and fast times became part of Rauch’s life, and these elements all coexisted with Rauch’s taste for fun.

Paul Butler, now chief executive of the International Racing Team Association (IRTA), was motorcycle competition manager for Dunlop during the 1960s and ’70s. He recalls, “Volker was of relatively slight stature, and he put up with a lot of banter about this. One of the jokes was, whenever he showed up in new clothing he’d be complimented about his jacket and then asked if it was made in men’s sizes. Volker was one of the few non-Brits covering GP racing at that time and he had to put up with a lot of teasing about his nationality. A lot of this sort of banter went on in airplanes, and a lot of non-racing passengers became confused at what looked like World War III breaking out. But he gave as good as he got, and he was always such excellent company that nothing was ever held against him. We didn’t think of him as anything but the world’s best photographer, and a good friend and companion. It is sad that we lost him.”

No one can say for certain what impulses pushed Rauch to his final outrageous act. A few clues can be pieced together, but how much of a complete picture they form may be forever unknown.

Foremost, though, is this: Hildegard remembers, “He was a man who loved the luxury. He loved to live the good life, to buy expensive things.”

That’s a side of Rauch’s character that Parkhurst remembers very well. He says, “He did love the good life. He loved beautiful women, and he partook of them as much as he could. He always had the fastest, newest BMW he could afford. He’d haul ass around town, just driving the balls off the thing. He’d eat at the finest restaurants and drink the finest wines, as long as they were German. And of course, German beer. He knew how to have fun. I’ll never forget, once he took me on a tour of the cathouses of Nürnberg. 1 don’t know if Hildegard knew about this. But he was very generous. 1 liked him a lot and looked forward to being with him.”

So, apparently, did the racers. Recalls Tony Mills, once a tire engineer for Dunlop, “He was quite well liked, and was a very good friend of Mike Hailwood. The factory teams allowed him into their backyards, and he frequently came up with stories other people hadn’t gotten.”

13ut 1er adds, “He was so successful with the teams and riders because he understood their business so well. Tie knew what motivated them and turned them on. We lived largely in the paddocks in those days, and he was one of the ones hanging around after the day’s work was done. As for his standards, well, he liked the best, and that was a commendable thing. The cars, the clothes, the watches, it w as part of his image, and I suspect that especially in his later years, it put quite a lot of pressure on his lifestyle.”

There were other pressure points, as well. Rauch’s stock in trade was blackand-white, which is, some would argue, the film of the artist. But the world turned to color film. In 1980 his lather left Das Motorrad, and Rauch found himself unable to work with the new editor, so he and Hildegard formed their own business-a sort of motorcycle racing news bureau, w ith Volker taking the photos and Hildegard writing the reports. Other photographers were catching up to him in terms of commitment and artistic ability, and other companies-notably Canon and Nikon-were catching up to Leica in terms of the quality of their photographic equipment.

Recalls Butler, “It was a much tougher world for him, as far as his trade was concerned. Life got a lot more competitive for all of us. It was clear from his demeanor that he had things on his mind. And he was having trouble with his photography. He’d got the shakes pretty bad, and he was having trouble taking pictures. In hindsight. I'd say he was showing signs of strain. But we never thought anything like that would happen. It’s unexplainable, really.”

What happened was simple. Volker Rauch no longer could afford to live in the way he’d become used to living.

Hildegard remembers, “Volker gave out more money than he earned. One day he had so many debts he could not pay them. We had a very intense argument about this when I found out. I told him I could not stand this, I must have some security. I told him ‘I have worked with you all my life. This has been my Hie. But now I'm going away from you.’”

So Hildegard left and Volker went to St. Moritz, that most classic of oldmoney Swiss ski resorts. Says Hildegard, “He was there six w'eeks, living in a hotel in hopes of making suicide with a paraglider. He tried several times to hire a glider, but he had six weeks of bad weather. So he jumped out a window.”

He died upon impact with hard Swiss soil.

Hildegard says, “I think they (Volker’s friends) blame me for Volker’s death, because everybody knows I parted, that I went away. But (Volker’s suicide) is not my fault. I know it inside. But the others don’t.” And then she adds, wistfully, “He was a good man, without bad thinking. He was a good guy and I never doubted that he loved me. He just lost sometimes the feeling for reality.”

Now, two years after the world’s greatest racing photographer leapt to his death, Hildegard Rauch has made for herself a new reality. But she hasn’t forgotten the old one.

She says of being separated from the racing world she came to love so much, “It hurt my heart.”

What remains with that hurt, packed away in Hildegard’s storage facilities, are more than 100,000 of Volker’s images. Many are ordinary—even the greats like Volker Rauch, after all, don’t manage to insert genius into every single piece of work. But many more of those images are immortal, showing the giants of racing’s golden age doing what they did best:

Agostini, Phil Reed, Kenny Roberts, Randy Mamola, and, most of all,

Mike Hailwood. What also remains is the tremendous influence Volker Rauch had on racing photography. Thanks to the professionalism he brought to the craft, today’s best racing photos arc art. If they’re not, they don’t get published.

And if, today, we see a great racing photo and marvel at the level of craftsmanship it took to produce it, we can be grateful that a compact German man with a very large talent raised the level of the craft, changing it as surely as sunlight changes photographic film. For that’s just what Volker Rauch did. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

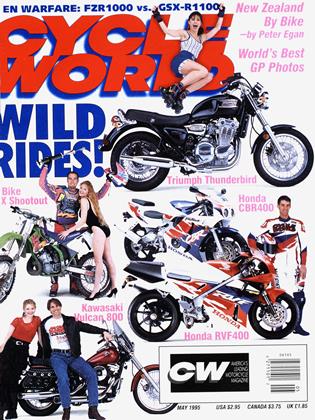

Up Front

Up FrontLove At First Ride

May 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsGlowing Inspirational Restoration Messages

May 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThe Mpg Papers

May 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's Storming Standard

May 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupTriumph's Getting Tubular, Going Raging

May 1995 By Robert Hough