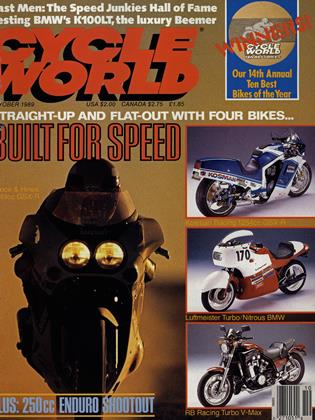

BUILT FOR SPEED

FOUR CASES OF SEVERE VELOCITY OVERDOSE

JON F. THOMPSON

PSSST! WANNA GO FAST-REALLY FAST? THEN SHAKE hands with four motorcycles built for speed. Conventional wisdom’s good, gray logic, which demands “Don’t fiddle with it," will take you only so far when you’re looking for speed, because without fiddling, you can't know what’s possible. Fiddling on an epic scale produced this rude quartet, motorcycles as raucous and uncompromising as green hair, the bad boys of the motorcycle world. They are the product of the wisdom which informs us that “Speed costs money,” then slyly asks,“How fast do you want to go?” These bikes all answer that question with a question of their own, one which completely ignores the realities of life on the streets. They ask, “How fast you got?”

Formulating an answer can be problematic if it’s streetbikes you’re talking about, because most will, right off the showroom floor, float the valves of any state trooper’s radar gun. But there’s more than one place to twist a throttle and recognition of that fact keeps aboil this intriguing question: How fast can a streetbike be made to go?

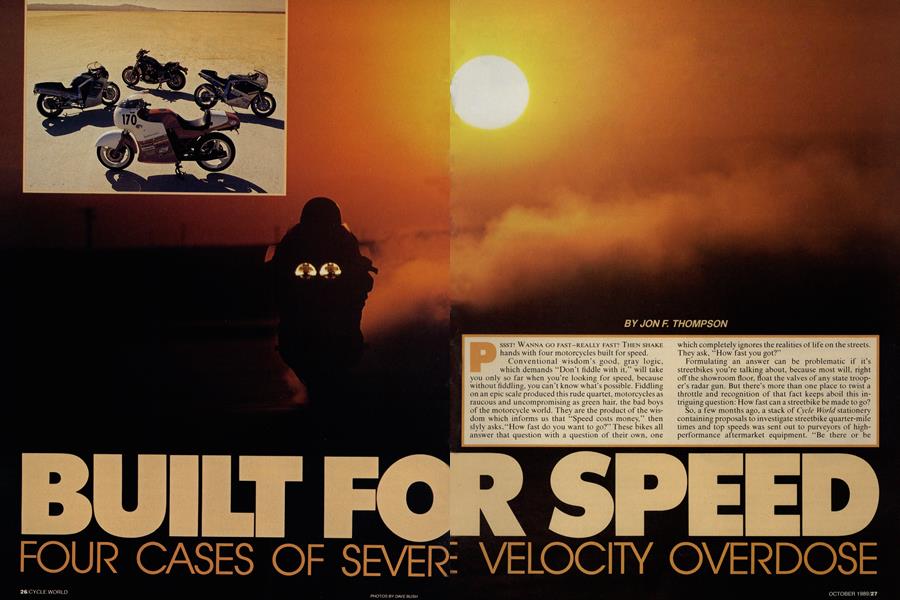

So, a few months ago, a stack of Cycle World stationery containing proposals to investigate streetbike quarter-mile times and top speeds was sent out to purveyors of highperformance aftermarket equipment. “Be there or be square,” basically was our challenge. Rule Number One was that all entries must be street-legal and must run on pump gas and DOT tires. Rule Number Two was that no mechanical changes, save carb-jet swapping, would be permitted between the dragstrip and top-speed runs. Rule Number Three was that there were no other rules. The four motorcycles you see here were delivered into CW's hands by Kosman Racing, Luftmeister Inc., RB Racing and Vance & Hines Racing.

Is there a place for streetbikes as unconventional as this foursome, bikes that will bump up against 175 miles per hour and rip off 9-second quarter-mile passes? Hey, why not? Unconventionality is the handmaiden of motorcycle riding—and a comely handmaiden she is, too. What these machines promise is that most basic of performance tradeoffs: The exchange of speed for money. So, wanna go fast—really fast? Step right up. So do we.

In order to do so, we organized a kind of motorcycling triathalon which would, we judged, equip our testing process with the necessary element of safety and good sense. First, we sedately flogged this quartet on a luncheon ride over the Ortega Highway, a favorite piece of twisty highway, to establish street viability.

Most streetable, but least sorted, was the RB Racing turbocharged, intercooled V-Max. Built at the last minute after RB's original entry, a customer-owned turbo-Harley, was pulled, the Max was strong, smooth and comfortable but never really ran properly. Least streetable but most sorted were the two Suzukis. The rear-suspensionless Kosman Racing GSX-R won the Cycle World Arbitrary and Capricious Style Points Award because of its felonious looks and because, those looks and its awesome performance notwithstanding, it was fully street-legal.

Beautifully sorted and blindingly fast, the Vance & Hines Suzuki GSX-R came perilously close to disqualification. Lack of mirrors, turnsignals and a license-plate holder, not to mention an actual license plate and registration paperwork, made this bike more than a little illegal for road use. Horrified, we bitched, so Vance & Hines stuck some (non-operative) rear turnsignals on and we hung some mirrors on the bike's fairing. And then we held our breath every time we saw a policeman.

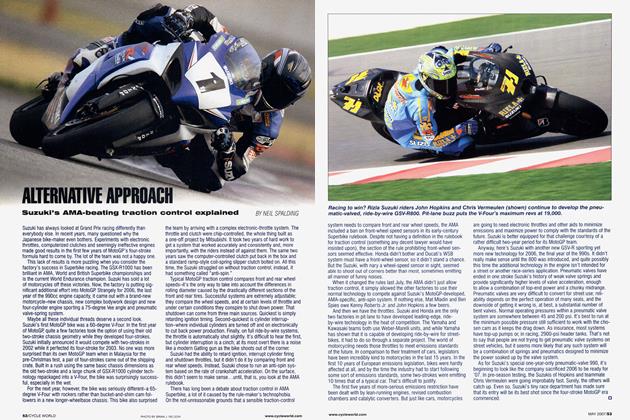

And finally, there was the Luftmeister BMW. a faired, turbocharged, nitrous-oxide-injected monster which makes an estimated 250 horsepower oriented towards finding 200 miles per hour at the Bonneville Salt Flats. Quiet, fun to ride, completely street-legal. Award style points for aggressive looks.

The guiding philosophy of this first leg of the project was to survive without mechanical or legal trauma until Day Two, dragstrip day, when throttles would get seriously yanked open. And despite some wayward glances from the local constabulary during our street ride, not one of these fearsome four was pulled over for closer inspection.

In preparation for Day Two, we telephoned drag-racing legend Jay Gleason and whispered, “Nine-second motorcycles” into his ear. He signed on immediately, so we hauled the bikes to Carlsbad Raceway, near San Diego. In spite of his warnings that the heat of the day was robbing us of horsepower, Gleason’s quickest time, 9.70 seconds at 147.78 miles per hour, was set at about noon on his last of 1 1 runs on the Kosman GSX-R. This machine also provided Gleason with his minimum daily requirement of terror: A throttle-slide screw in the bike’s number-three carburetor came adrift during a pass, jamming the throttles wide open. “Anybody got any clean underwear?” a shaken Gleason asked afterwards.

For all the dragstrip specialization of the Kosman Racing bike, neither the Vance & Hines GSX-R nor the> Luftmeister BMW, each oriented towards very different kinds of performance, was too far off the pace. The V&H bike entertained anyone who rode it with wheelies of the moon-shot kind, courtesy of its short wheelbase and good traction from its Dunlop K591 tires. Nevertheless, it recorded the second-quickest time, with a 9.91-second, 147.54-mph pass. For reference, the quickest and fastest stock streetbike Cycle World has ever tested is this year’s Yamaha FZR100Ö, which knocked off a 10.39 at 134.52 miles an hour.

Next up was the Bonneville Beemer, which Gleason pushed through the traps in 10.12 seconds at 149.50 miles per hour. And on a final go-for-broke run, his thumb mashing the nitrous button through both third and fourth gears, Gleason flogged the BMW to a slightly slower 10.22-second ET but clocked a lusty 152.80 miles per hour while doing so.

On this final run Gleason said he climbed out of the BMW’s throttle early because the bike’s prodigious turboand nitrous-fed power was flexing the chassis and swingarm enough to point it off the right side of the track. Better him than us.

The turbo V-Max? In spite of the best efforts of RB Racing’s Bob Behn, who rejetted the bike’s complicated carburetion system six times during the course of the day and who tried the bike both with and without its V-boost induction system, it managed no better than a 10.91-second, 125.17-mph run, popping and banging the whole way. We should note that our stock 1988 test V-Max turned a 10.88-second, 125.00-mph quarter-mile pass when we evaluated the machine in last August’s issue.

After a day at the strip came our triathalon’s final leg, the one which had “175 miles per hour’’ written all over it. For this, we obtained permission from the Bureau of Land Management to use El Mirage Dry Lake, a high-speed shrine in the Mojave Desert near Victorville, California. Associate Editor Doug Toland would ride.

A word about the dry lake and the speeds it yielded: El Mirage is a white, flat pan of fine, packed silt which seems made for the purpose which brought us there. But there’s an oddly contradictory caveat to be associated with running at El Mirage. It is that here, speeds are slower than they would be on pavement. That’s because the lake surface is softer than asphalt and provides poorer traction. And when speeds rise, so does aerodynamic resistance. Some of the horsepower which on pavement would work to overcome that resistance instead gets spent in wheelspin on the lake bed’s soft surface, even under optimal conditions.

And conditions weren’t optimal for our dry-lake day. El Mirage is studded with clumps of puckerbushes and ravaged by ruts. Though regulation speed traps, laid out and manned for us by veteran Southern California Timing Association and Bonneville Speed Week timer Gary Cagle, require but 1 32 feet, the requirements of running at the speeds we envisaged dictated finding a perfectly flat, straight stretch no less than 1.5 miles long. The course we finally settled on reflected this difficulty. It was straight and flat and long, but it contained a compromise in the form of a soft section just ahead of the speed trap. This section yielded wheelspin on each of the bikes, wasting power which on a paved surface would have been translated into speed.

The official top-speed record on El Mirage on this particular day was owned by the Vance & Hines GSX-R, which cranked off an awesome 173.176-mph pass on Toland's first run.

With such a strong performance from the Suzuki, 190 miles an hour from the BMW seemed in the air; we could smell it. But as the heat quickly rose on this desert lake bed, we also could sense the horsepower draining from the atmosphere just as water runs down a bathtub drain. And though the BMW did manage one unofficial 186.683mph pass during a tuning run with its owner/builder up, and though it had made a 191-mph pass here during a recent SCTA meet, its best official run with Toland at the controls was 1 71.265 miles per hour.

Toland dug deep to find more speed, but the bike’s breathtaking power just spun the rear wheel, causing the beast, on one try-hard run, to fishtail so violently in the soft section just before the timing lights that photographer Dave Bush, stationed adjacent to the lights, saw first one side of its fairing and then the other. Was there more speed to be found in the BMW? Perhaps. But before we could find it, the bike’s high-steroid engine ate a piston.

Next up came the Kosman Racing GSX-R and there were no surprises here. This machine, constructed to achieve its maximum speed in 1320 feet, easily reached its rev limit in top gear long before the timing lights and flashed through them at 158.20 miles per hour. But this came only after a frightening incident requiring some hurried work on the bike. On the bike’s first pass, at more than 1 50 miles an hour, the left side of its fairing pulled loose from its mounts, and the resulting aerodynamic imbalance threw the bike sideways as though it had been hit by muzzle blast, scaring the daylights out of Toland. The bike was repaired with parts scavenged from other equipment and went on to make its 158.20-mph run and then, unfortunately, blow a head gasket. The lesson is that even on the most-meticulously prepared bikes, things happen, and the faster you go, the faster they happen.

Finally came the turn of the RB Racing Turbo-Max, the jetting of which RB’s Bob Behn still was struggling with. No progress there, and no luck, either: The bike’s megamotor holed a piston in the hot, dry-lake-bed atmosphere before it got up to speed, giving RB last place in the top-speed runs as well as in the dragstrip competition, and earning OFs unofficial Hard Luck Trophy.

So, now we know how quick and how fast streetbikes can be made to go, and the lessons to be learned seem obvious. First, no matter how complete your preparations are, on some days you just won’t reach your performance targets. Second, that ageless equation, stated “Speed costs,” remains in force. Every single mile per hour in excess of what a machine is capable of in stock form is very expensive indeed, in terms of dollars and in terms of compromised reliability.

But this knowledge has never stopped the truly hungry. The kind of performance displayed by these special motorcycles may be academic in that it is affordable only to a few and is within the capabilities of even fewer. But for those willing to make the preparations, set their goals and spend their bucks, it’s enough to know that if you really must have more speed, all you have to do is decide how much you’re willing to spend.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

October 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

October 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

October 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1989 -

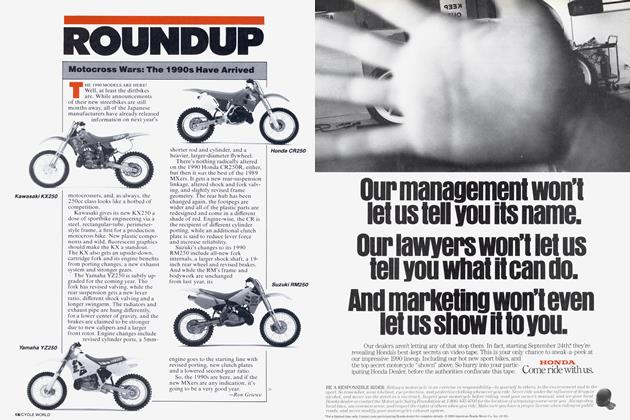

Roundup

RoundupMotocross Wars: the 1990s Have Arrived

October 1989 By Ron Griewe -

Roundup

RoundupThe Harley-Davidson Success Story

October 1989 By Jon F. Thompson