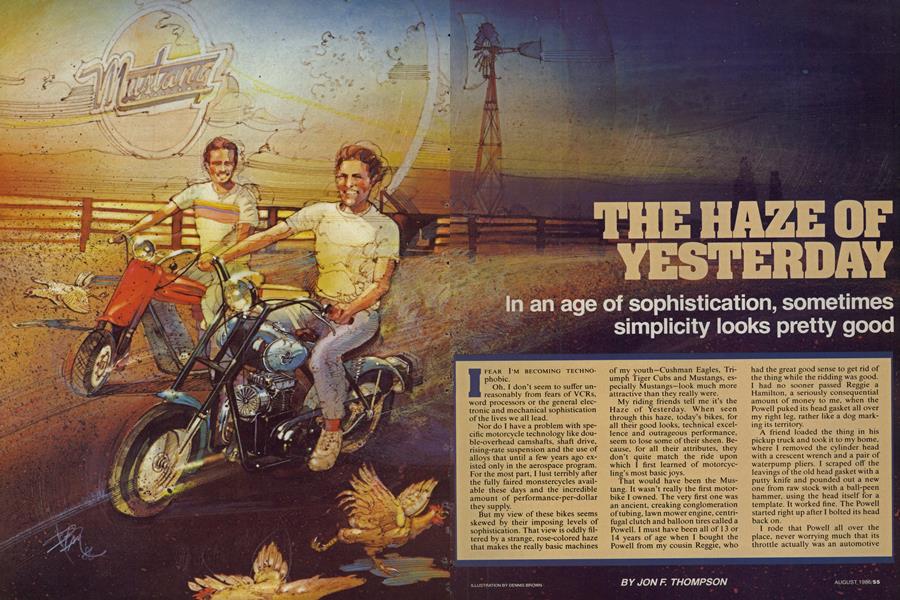

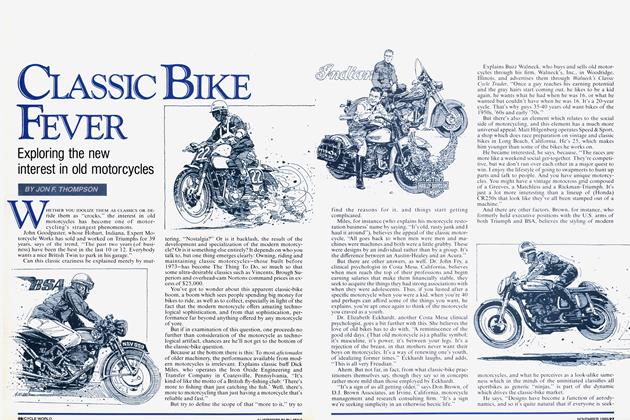

THE HAZE OF YESTERDAY

In an, age of sophistication, sometimes simplicity looks pretty good

JON F. THOMPSON

I FEAR I'M BECOMING TECHNOphobic. Oh, I don't seem to suffer unreasonably from fears of VCRs, word processors or the general electronic and mechanical sophistication of the lives we all lead.

Nor do I have a problem with specific motorcycle technology like double-overhead camshafts, shaft drive, rising-rate suspension and the use of alloys that until a few years ago existed only in the aerospace program. For the most part, I lust terribly after the fully faired monstercycles available these days and the incredible amount of performance-per-dollar they supply. ____

But my view of these bikes seems skewed by their imposing levels of sophistication. That view is oddly filtered by a strange, rose-colored haze that makes the really basic machines

of my youth—Cushman Eagles, Triumph Tiger Cubs and Mustangs, especially Mustangs—look much more attractive than they really were.

My riding friends tell me it’s the Haze of Yesterday. When seen through this haze, today’s bikes, for all their good looks, technical excellence and outrageous performance, seem to lose some of their sheen. Because, for all their attributes, they don’t quite match the ride upon which I first learned of motorcycling’s most basic joys.

That would have been the Mustang. It wasn’t really the first motorbike I owned. The very first one was an ancient, creaking conglomeration of tubing, lawn mower engine, centrifugal clutch and balloon tires called a Powell. I must have been all of 13 or 14 years of age when I bought the Powell from my cousin Reggie, who

had the great good sense to get the thing while the ridding was good.

I had no sooner passed Reggie a Hamilton, a seriously consequential amount of money to me, when the Powell puked its head gasket all over my right leg, rather like a dog marking its territory.

A friend loaded the thing in his pickup truck and took it to my home, where I removed the cylinder head with a crescent wrench and a pair of waterpump pliers. I scraped off the leavings of the old head gasket with a putty knife and pounded out a new one from raw stock with a ball-peen hammer, using the head itself for a template. It worked fine. The Powell started right up after I bolted its head back on.

I rode that Powell all over the place, never worrying much that its throttle actually was an automotive

"I was shipped off to school... the Mustang was banished to a barn, eventually to become a victim of time."

choke knob mounted on a psuedodash and that when you wanted to stop, you dragged your feet. Unless you wanted to stop really fast, in which case you fell over.

The Powell served me handsomely for a while, and in my own way I was proud of it. But there were others in the desert agricultural community where I lived that had picked up on the newest Hot Tip: The Cushman Eagle, which, in its day, was about as slick a scooter as you could find. The trouble was, it was a scooter, no pretense about it. My satisfaction demanded more than that. I read all the motorcycle magazines. I dreamed of an AJS, at least, perhaps even a Norton, never mind that my allowance, derived from doing chores around the ranch, could barely keep the Powell alive and that my parents’ good sense precluded the kind of performance an AJS, say, would have delivered.

Then one day the Mustang arrived.

I had never seen anything like it. It was beautiful. A 1 948 Model 2, it was a real, honest-to-goodness almostmotorcycle in five-eighths scale. Powder-blue and white, it was, with solid disc wheels, a sliding front fork, a hard tail, a three-speed transmission and funny little square-shouldered tires straight off a Nash Metropolitan.

It had a real engine, too, a screaming little 3 1 5cc one-lunger fueled by an Amal carburetor. I had digested enough motorcycle magazines to know that Amal carburetors fueled the engines of some of the best roadracing bikes in the world. If the Amal was good enough for them, it was good enough for me, even if it did leak just a little and contained more whistles, bells and springs than I’d ever seen in the Ford tractor and Chevy pickup carburetors I was used to fiddling with.

The engine was a side-valve design, and it was said that the piston and valves were from a flathead Ford V-Eight. It also was said that if you wanted a bit more horsepower, you hogged out a little metal and slid the piston and valves from a Lincoln VEight into the tiny block. I never learned if that was true. But I took great comfort from the knowledge that if more performance proved necessary, an easy hop-up was right around the corner.

The Mustang appeared because my father figured The Time Was Right. He’d cut his teeth—and select other parts of his body—on a Harley 45, even rode one over a cliff once and landed in a treetop with just moderately severe consequences. I guess he figured that motorcycling had worked out well enough for him, with a minimum of time spent in the local emergency room and all, so a bike probably would work out fairly well for me. My mother, protective as mothers are supposed to be, was rather less certain about this.

There was no doubt in my mind, however. Wasn’t then, isn’t now. That Mustang went to its grave more than 25 years ago, and in intervening years I’ve owned, ridden, cared for and abused more equipment than you can shake a torque wrench at, but only a few pieces have delivered the satisfaction I derived from that bike.

I’m not really certain why, except perhaps that the Mustang was absolutely pure: There wasn’t anything on it that didn’t make it go faster, with the possible exception of one concession to form—a rear fender that had been stylishly bobbed. But that kept the mud spray and general farmanimal leave-behind from being flung up onto my back by the hand-cut knobby rear tire as I sped past the feed lot, swallowing the oc-

casional fly lucky enough to make it past the barrier of my teeth. So the fender stayed on.

The Mustang came to me at least thirdor fourth-hand. It had not been treated kindly. Its lighting system had been taken out of commission, and somehow, the flywheel, which was externally mounted on the righthand side of the crankshaft, had an odd look to it. That’s because it wasn’t the correct flywheel. I never learned—indeed, never asked—how the original piece turned up missing in action. But by the time the Mustang became mine, in place of the original was a flywheel from, of all things, a Cushman Eagle, with its cooling fins machined off. It had been rekeyed so that the ignition timing was right for the Mustang’s engine.

And it was right. That wonderful little engine never needed more than three kicks to start it. When it bolted into life, it ticked over with a fine, reassuring, single-cylinder thump, vibrating the rest of the bike wonderfully, mercilessly, with each combustion stroke, and delivering wonderful amounts of horsepower from ultralow rpm all the way up to what seemed then like infinity.

Aboard the Mustang, I was much faster than the plebes on their Eagles. Never once did I mention that my mount owed its spark to the Cushman factory and a clever machinist.

The only serious problem with the bike was that its British-built Burman transmission never worked quite right. Those who knew about such things told me its shifting dogs were worn. And they pulled off a transmission sidecover to prove it. I knew little of such technicalities and cared even less. I just wanted the thing to shift, which it did about half the time. The other half it was stuck in second

gear—a better gear to be stuck in than either first or third, to be sure.

So I thanked the Lord for small favors and gassed it; with a little slipping of the clutch the Mustang was still quite ridable. And if I played my cards right and kept trying, once in a while I could find first and third gears. When that happened, all truly was right with the world.

But nothing is forever, and my bliss on that little two-wheeled jewel had but a few months to live. One day, while flogging around the turkey pens not far from where the Powell had eaten its head gasket, disaster struck. I was traveling as rapidly as I knew how, with the engine wound out in second gear, in which, as usual, the transmission was stuck. The Mustang’s crankshaft was a hardy piece but it had not been built for such prolonged rpm, certainly not with an out-of-balance, oddball flywheel clamped onto one of its ends. So it took the most direct route towards the elimination of such abuse: It broke, right at the right-hand seal; and the crankshaft tip, flywheel still attached, went sproing, off into the weeds, narrowly avoiding the amputation of my right foot on the way.

From then on the Mustang remained silent—a turn of events for which my mother was quite grateful.

I knew deep in my pubescent heart that the next logical step was to bypass the engine rebuild. I knew that what was called for was a brand-new Mustang. There was a dealership right up the road in town, wedged in between the tractor and farm-implement stores, and there on the floor sat a shiny new Thoroughbred with chromed-spoke wheels, a four-speed transmission and rear suspension that really worked. It was jet black, with a wide chrome strip running down the middle of its tank. I hope

that whoever finally bought that bike took better care of it than I would have. It deserved better than that.

I deserved what I got: shipped off to school, my days of wahooing around the ranch at an end. The crankless Mustang was banished to a barn, eventually to become a victim of time.

Now, more years later than I care to count, the age of the Japanese multi-everything supercycle is upon us. Oh, these bikes are practical, all right, even if the accompanying tuneup bills, replacement-part prices, speeding tickets and insurance premiums are sometimes distressing.

I guess that, maybe, on a gray, wet day like today, I don’t need practicality. I need better than that. I need a rose-tinted, blue-and-white almostmotorcycle, the name of which most motorcyclists wouldn’t even recog-

nize. Because, you see, when you’re dealing with such a machine, you can ride from here to Buffalo and backshould you wish to do such a mad thing—and never get wet, never get cold, never fall down, never get a speeding ticket and never once have a breakdown.

Tomorrow? That’ll be tomorrow, a whole new deal. Perhaps it’ll be sunny and warm. And perhaps I’ll need quite desperately to light up the 1100 that lives in my garage and howl off to terrorize the first canyon I can find. But for now, the Haze of Yesterday is in place, and that little blueand-white Mustang looks about as good as anything I’ve seen.

And for now, the reassuring thump of that single Ford flathead V-Eight piston is one of the most alluring sensations I could hope for.

Just for now, while the Haze lasts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue