MAD MEL RIDES AGAIN

Firing up the World's Fastest '69 Honda, Vol. II

JON F. THOMPSON

THIS IS WHAT I'M SAYING: HERE IT IS, THE WORLD’S fastest 1969 Honda. It's back.”

That's what Mad Mel Mandel is saving, all right kind what he's also saying is that after a long recuperation from an accident that crushed both him and his motorcycle, he's back, too, as obsessed with speed as ever. But it’s got to be the right kind of speed. Mandel has no time for effete, limp-wristed, candy-assed, flick-around-corners, canyon-racer speed. His idea of speed is Good Old American Straight-Line Haul-Ass.

“My claim to fame is. if you threaten me, that's w here I turn it on. When I ride. I mind my own business. But if you threaten me,” he says, indicating his bike, “it switches from '69 Honda to "Kill.' If you come up next to me and want to race, now you're in my world. I've never lost. Nobody’s ever been in front of that license plate." And he adds, grinning. “I've felt like Dr. Frankenstein building

the monster.”

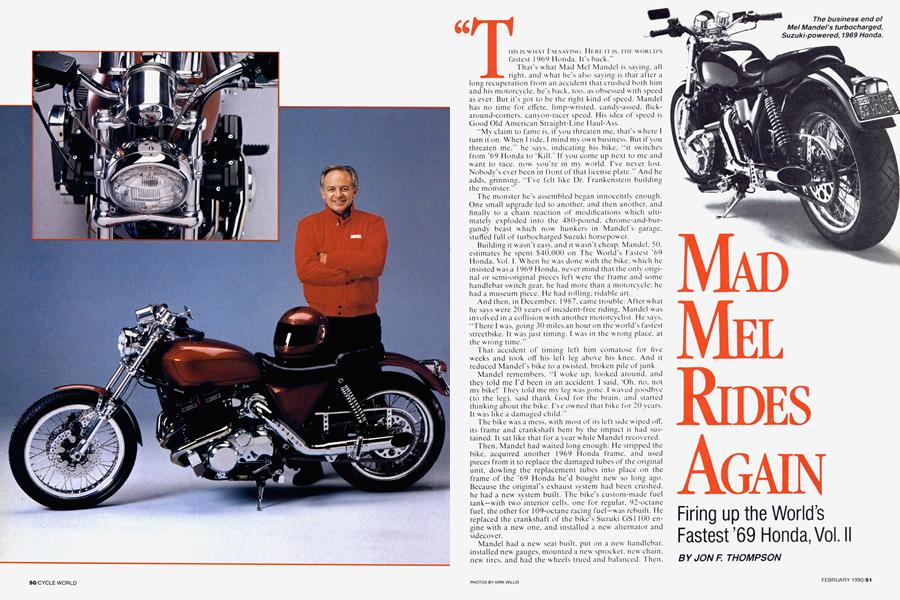

The monster he's assembled began innocently enough. One small upgrade led to another, and then another, and finally to a chain reaction of modifications which ultimately exploded into the 480-pound, chrome-and-burgundy beast which now hunkers in Mandel's garage, stuffed full of turbocharged Suzuki horsepower.

Building it wasn’t easy, and it wasn't cheap. Mandel. 50. estimates he spent $40.000 on The World's Fastest '69 Honda, Vol. I. When he was done w ith the bike, which he insisted was a l 969 I londa. never mind that the only original or semi-original pieces left were the frame and some handlebar sw itch gear, he had more than a motorcycle: he had a museum piece. He had rolling, ridable art.

And then, in December. 1987, came trouble. After what he says were 20 years of incident-free riding, Mandel was involved in a collision with another motorcyclist. He says, “There I was. going 30 miles an hour on the w orld’s fastest streetbike. It was just timing. I was in the wrong place, at the wrong time.”

That accident of timing left him comatose for five weeks and took off his left leg above his knee. And it reduced Mandel's bike to a twisted, broken pile of junk.

Mandel remembers, “I woke up. looked around, and they told me I'd been in an accident. I said. ‘Oh. no, not m\ bike!' They told me my leg was gone. I waved goodbye (to the leg), said thank God for the brain, and started thinking about the bike. I've ow ned that bike for 20 years. It was like a damaged child.”

The bike was a mess, w ith most of its left side wiped off. its frame and crankshaft bent by the impact it had sustained. It sat like that for a year while Mandel recovered.

Then, Mandel had waited long enough: He stripped the bike, acquired another 1969 Honda frame, and used pieces from it to replace the damaged tubes of the original unit, dowling the replacement tubes into place on the frame of the '69 Honda he'd bought new so long ago. Because the original’s exhaust system had been crushed, he had a new system built. The bike's custom-made fuel tank-with two interior cells, one for regular. 92-octane fuel, the other for 109-octane racing fuel—was rebuilt. He replaced the crankshaft of the bike's Suzuki GSI 100 engine with a new one, and installed a new alternator and sidecover.

Mandel had a new seat built, put on a new' handlebar, installed new' gauges, mounted a new sprocket, new chain, new' tires, and had the w heels trued and balanced. Then, he sent everything out to be either plated or painted, his objective being to restore the bike to exactly its condition before the accident.

About the engine: Mandei is more than a little vague about its contents, and his vagueness doesn't come from the usual street-racer’s coyness. He knows that its gears are all straight-cut, and that engine and transmission internals have been hard-chromed to reduce friction losses. But as for the details of the rest, he’s content to let Vance & Hines, which built the engine for him. worry about that. He does know that prior to the crash, it was making a claimed 265 horsepower and turning 10-second, 155-mph quarter-miles without a wheelie bar, supporting Mandel’s “world's fastest streetbike" claim. Even the four “Built for Speed" bullets in Cycle Worlds November. 1989, issue wouldn't match Mandel’s bike for speed at the dragstrip, though three did post better elapsed times.

And. while the bike was in pieces for its post-crash rebuild, Mandel, who says he likes what he calls “passing power,’’ had the motor stepped on. He estimates it now produces about 280 horsepower.

The result is The World’s Fastest ’69 Honda, Vol. II. a motorcycle of stunning beauty and impeccable detail work, with no rough edges anywhere, a motorcycle which rewards close inspection with the discovery of several clever touches.

For instance, because the turbo on Mandel's engine provides 22 pounds of boost, to avoid piston-holing detonation, it requires water injection, an arrangement that can be bulky and unlovely to look at. But this system is hidden, along with the engine's oil-overflow system and the airtank for the bike’s air shifter, in the custom-built Calfab swingarm. Another for-instance: To help him keep track of the bike’s sundry non-stock systems, Mandel has installed in its headlight shell, mounted atop a highly polished Ceriani fork, tiny lights which gleam like rubies when, for example, he switches to his racing fuel, or when, prior to a run. he manually boosts the oil pressure to the bike’s turbo unit, or when he activates the system that keeps his up-and-down air shifter—required now by the absence of a shifting foot —loaded with compressed air.

Mandel loves the interest the bike gets from curious chassis-sniffers. He says, very much the proud father as visitors explore the bike's surprises. “It’s a very trick piece, lemme tell you.’’

Mel Mandel, however, complete with artificial, carbonfiber-and-magnesium left leg. may be the most-trick piece of all. After an accident that nearly killed him and that destroyed a motorcycle into which he'd invested a fortune, he still wants to ride.

“It’s instant therapy." Mandel explains, “it's the mostbeautiful thing: all that power under you. Working on the bike has been the greatest therapy. It even helped bring my memory back. This bike has done so much for me. It’s a love affair, or some darned thing."

Now, though he’s back to work as a courier for NBC news crews in Los Angeles, Mandel is still trying to come to grips with the problems associated with riding sons left leg. He isn't completely comfortable on the bike, he says, at least in part because he’s having trouble keeping his artificial foot placed on the bike’s footpeg.

“If I can't work out the problems so I'm comfortable riding the bike. I'll sell it." threatens Mandel.

Well, maybe. Mandel has, it seems, become very adept at working out problems, whether they pertain to the twowheeled piece of art he rides, or to overcoming the physical problems he’s faced. But, who knows, maybe he will give up and sell his bike.

Seems a long shot, though, after all Mandel and this motorcycle have been through together. A better bet would be that he keeps on riding, and that his “ 1 969 Honda" never leaves his hands. B3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

February 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

February 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

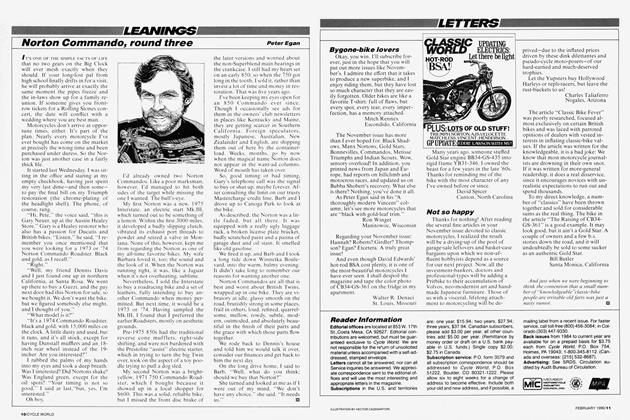

ColumnsLeanings

February 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupForza Italia! Milan Show Highlights

February 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

Roundup1990 Ducatis, Husqvarnas: Don't Call 'em Cagivas Anymore

February 1990