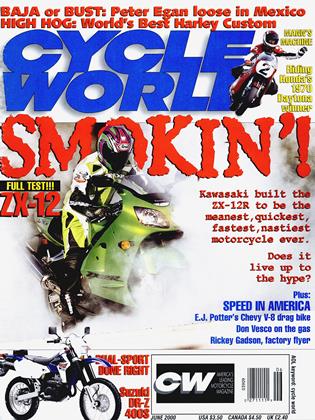

Daytona Drama

RACE WATCH

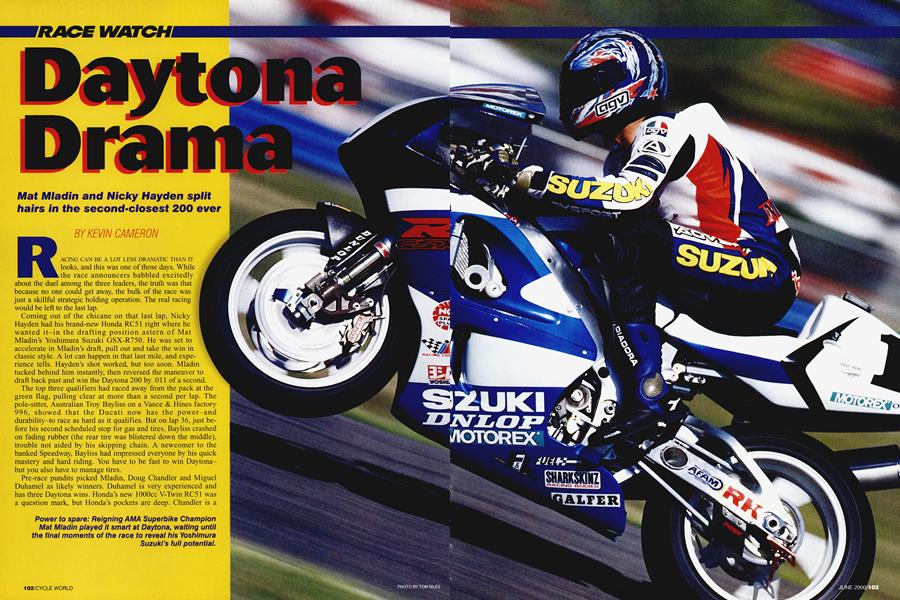

Mat Miadin and Nicky Hayden split hairs in the second-closest 200 ever

KEVIN CAMERON

RACING CAN BE A LOT LESS DRAMATIC THAN IT looks, and this was one of those days. While the race announcers babbled excitedly about the duel among the three leaders, the truth was that because no one could get away, the bulk of the race was just a skillful strategic holding operation. The real racing would be left to the last lap.

Coming out of the chicane on that last lap, Nicky Hayden had his brand-new Honda RC5l right where he wanted it-in the drafting position astern of Mat Mladin’s Yoshimura Suzuki GSX-R750. He was set to accelerate in Mladin’s draft, pull out and take the win in classic style. A lot can happen in that last mile, and experience tells. Hayden’s shot worked, but too soon. Mladin tucked behind him instantly, then reversed the maneuver to draft back past and win the Daytona 200 by .011 of a second.

The top three qualifiers had raced away from the pack at the green flag, pulling clear at more than a second per lap. The pole-sitter, Australian Troy Bayliss on a Vance & Hines factory 996, showed that the Ducati now has the power-and durability-to race as hard as it qualifies. But on lap 36, just before his second scheduled stop for gas and tires, Bayliss crashed on fading rubber (the rear tire was blistered down the middle), trouble not aided by his skipping chain. A newcomer to the banked Speedway, Bayliss had impressed everyone by his quick mastery and hard riding. You have to be fast to win Daytonabut you also have to manage tires.

Pre-race pundits picked Mladin, Doug Chandler and Miguel Duhamel as likely winners. Duhamel is very experienced and has three Daytona wins. Honda’s new lOOOcc V-Twin RC51 was a question mark, but Honda’s pockets are deep. Chandler is a supreme craftsman-an asset at the Speedway. Reigning champion Miadin is known for his methodical approach, and his Suzuki would be fast. Most discounted Ducati's chances despite

that make's history of pole positions. Ducatis, optimized for shorter World Superbike races, have always been Daytona-detuned at the ith hour to save them from mechanical or thermal failure. Not this time. I asked Jim Leonard. the very experienced Vance & Hines crew chief, how this came about. In the past, he said, it had been necessary to back down the compres sion slightly, and alter the ignition map-both in the interest of reducing combustion heat. In the neat, compact Ducati package, there was no room for more cooling without a drag inducing increase in frontal area. Why can the engines take it today? The

key, he explained, is greatly increased mechanical reliability, and that has come through tighter quality control.

The second V&H Ducati, ridden by Steve Rapp, finished sixth. Aaron Yates, back on a Suzuki after a lackluster year with Kawasaki, would qualify eighth and finish fifth.

The new Honda RC51 Twins were almost perfect in this, their first com-

petitive outing, having only minor problems such as broken exhaust springs. Otherwise, they never missed a beat and their handling was manageable, The riders liked them and there were zero unscheduled engine changes. Duhamel would start qualifying late. He was handicapped by a painful neck crick that required treatment and left him stiff and delicate. Despite this, he qualified fifth and finished fourth.

While Honda had a new motorcycle, Kawasaki had a new team. After many years of contracting roadracing to Rob Muzzy, Kawasaki has now taken it in-house under the direction of former Jet Ski race manager Michael Preston. The new team was assembled rapid-

ly and worked well with masses of new equipment. As Eric Bostrom’s mechanic AÍ Ludington observed, change brings opportunity.

“At Honda (where Ludington was Duhamel’s mechanic for years), it might take four months to get a new shock anchor point on a frame-drawings, meetings, priorities. But because Kawasaki has something to prove now, when we asked for a change, the Sawzalls came out right away, and in a few minutes the pivot was being welded into the new location.” Bostrom, who had a poor season in 1999, qualified ninth and finished eighth.

Kawasaki also had big new pit “war

wagons”-carryalls that transport everything the team needs from garage to pit wall. They also fight the clutter that naturally forms around a race team, keeping tools, parts and hoses organized. The bikes were a departure, covered with trick factory parts of obvious World Superbike origin, not intentionally stock-appearing as in the past. Chandler, the “master of smooth,” qualified sixth after being fastest in early practice. He then finished third after a late-race duel with Duhamel.

Kawasakis have been down on power both here and in World Superbike for some years, while Ducati and Honda have held the horsepower high ground. This past year, Kawasaki achieved stronger acceleration in World Superbike racing, and this obviously helped Chandler at Daytona. Radar trap speeds showed the factory Hondas, Suzukis and Ducatis on top

with speeds in the 177-179-mph range. Equally fast was Larry Pegram, who had organized his own privately backed program with Ducati. He then qualified on the front row. A slow pit stop and a fading chassis setup relegated him to a disappointing 10th in the race-still top privateer. This kind of small, well-managed team could be the future of racing if the factories one day decide to pull out.

The Kawasakis were 6-8 mph down from the top bikes, showing that the compromise between top speed and acceleration is no easier to make now than it has ever been. Engines need a high compression ratio to make torque for acceleration, but the higher the compression is set, the tighter, and therefore slower burning, the engine’s combustion chambers become. This, in turn, limits top-end power. If the

combustion chamber is opened up in the interest of rapid combustion and good top speed, acceleration suffers from the reduced compression ratio.

How do you get both? First, you make the combustion chamber as small in diameter and internally smooth as possible, to sustain the mixture turbulence that gives a fast burn. You may also try smaller valves and ports, to fill the engine with high er-velocity flow. Then, you instrument test heads with a forest of ionization gauges to map flame travel and speed. You also study in-chamber flow pat terns using a device called a laser anemometer. After many trials and much expense, you may find your

wa~ to a design that both accelerates and "top-ends" strongly. About that time, the product-planning committee decides the market needs a shorter stroke, larger-bore design that can rev higher and, theoretically, make more power. All this combustion research then has to be painstakingly done over again to make fact out of theory. Yamaha, with its signature five-

valve Genesis cylinder head, is also behind this particular 8 ball. Even with smallish valves, tightly clustered to form a relatively compact combustion space above each piston, five valves produce a wider, vertically thinner and therefore slower-burning chamber than do four valves. Yamahas won Daytona, but it’s tricky to make a five-valve chamber burn as efficiently as a four-valve. With its new YZF-R7 engine, Yamaha is down in the basement of its learning curve and has a lot of work to do.

This view of engine design makes us appreciate the advantage Ducati enjoys from its 15 years with the same basic engine; they know it really well now. It does not explain how Honda has stepped in with a brand-new design, ready to cross swords with the fastest. Honda people have revealed that this is the fourth generation of this design, and that there have been problems (surprise!). While some test engines have run with titanium rods, small-end seizures and piston-skirt scuffing reportedly forced the use of steel rods (substantially heavier than titanium) in the Daytona engines. The opposition fears there’s more to come from the RC 51.

Yamaha’s Jamie Hacking, injured during Friday’s 600 Supersport race, qualified 10th for the 200, but did not start. Tommy Hayden on the other YZF-R7 qualified just behind him and finished a creditable seventh. Although this bike’s 1999 debut in the U.S. was encouraging, the team admits it is still seeking a good overall chassis setup.

Suzuki’s garage was the least cluttered of all, and the Yosh team worked unhurriedly and neatly. The bikes, positioned in the center of large spaces, seemed like shrines in well-kept temples. The team had spent a day at Willow Springs doing nothing but pit-stop rehearsal, and had new wheelchanging systems that, in the words of

team mechanic Vic Fasola, were “really slick.” As before, their pre-race pit-stop practice was relaxed and confident. In the race, the pit duels with Honda and Vance & Hines were quick

and slotted Mladin back on the track with no position loss. If anything, Suzuki’s stops had a slight advantage. Pit stops are much the same for all teams. When a machine pits and the > jacks lift it, both axles are airwrenched and pulled back to their stops. Mechanics lift the wheels out as springs swing front brake calipers aside to clear rims and tires. New wheels with fresh rubber are dropped into place onto receivers that position them so the axles push straight in. All wheel spacers are captive. Front calipers have guides that slot brake discs between the pads without struggle. The air wrenches rattle and, as the fuel quick-fill is lifted from the tank, the jacks drop and the rider pulls away. New for this year were overhead gantries that kept air hoses out from underfoot. Neat.

The very slickness of what it now takes to win Daytona has worked to thin the entry list. With only 52 qualifiers, the AMA’s reasonable 112 percent qualifying rule was waived in the interest of finding the traditional 80 starters. The rule excludes those slower riders whose lap times are more than 112 percent of the pole time. With Bayliss’ pole time at 1:49.075, the 112 percent would come at 2:02.164. For comparison, consider that Kurtis Roberts, pole-sitter in the 600 Supersport race, qualified for that event in 1:54.147, on DOT rubber. That would have put him 14th on the Superbike grid. Understandably, in this climate of super-professionalism,

privateers see less point in wearing out their Supersport rides in the 200. You can’t have it all-glamorous factory teams and heart-warming do-ityourself success stories. Hard-working Pascal Picotte put his factory Harley-Davidson VR1000 in ninth place after another difficult Speed Week for the orange-and-black team. Fuel that had worked well a year ago now chopped top speed and detonated, leaving mechanics looking down the intake ports for big pieces, and scrambling to arrange supplies of an alternative fuel. Lots of engines were changed, and Scott Russell’s bike stopped in the race after a period of slow running and pit stops. Despite the team’s new swingarm and rear linkage, it looks like they are just holding the fort with the VR while preparing something better. Manager Steve Scheibe denies the existence of a new engine, but if you’re trying to hammer nails with your forehead, sheer persistence doesn’t help much. That glitzy relationship with Ford has to be good for something! I want to see it proved that people named Smith or Jones can design successful racebikes.

As I watched qualifying on Thursday, I could see that the quick times belonged to the teams that were the least busy. The more a team thrashed, the slower its riders seemed to be. The best-prepared teams had done their work at home, and it showed. It’s also interesting to compare the same teams in Superbike and 600 Supersport qualifying sessions. While 600 success sells bikes, Superbike is what really excites racing professionals, and you could see it. During Superbike

sessions, crews stared up-track, looking tense and completely focused. During 600, they were visibly more relaxed. There were many Japanese engineers and technicians in the factory garages, and the competitive atmosphere was thick.

Last year’s qualifying record set by Anthony Gobert on a Ducati still stands because Thursday this year was so hot. Leonard said that if a rider went too hard on his out-lap, he wouldn’t get a whole good qualifying lap before his rear tire “over-temperatured” and went off-which is just what happened to Mladin on his final effort. It was small disappointment to

him-he had put his hardest work into testing on race tires, and he won when it counted-in the race itself.

This year’s Daytona 200 signals a big change in personalities. The older stars such as Russell, Chandler and Duhamel are still potent, still respected, but it’s clear that the future belongs to the flood of youngsters with the capable Nicky Hayden currently at their head. Mladin, at the top of his game, stands between these groups.

The race on Sunday was almost anticlimactic, drawing a line under the long week of intense activity and effort, taking a simple sum of an infinitely complex and fascinating process. That’s racing. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Great Clinton Land Grab

June 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsOuter Daytona

June 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCWays And Means

June 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

June 2000 -

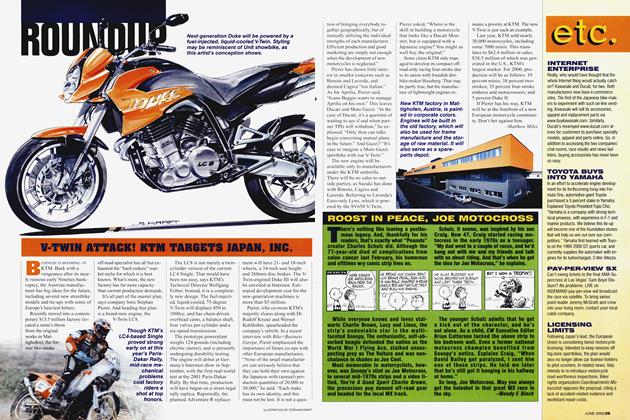

Roundup

RoundupV-Twin Attack! Ktm Targets Japan Inc.

June 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupRoost In Peace, Joe Motocross

June 2000 By Wendy F. Black