FLAT-OUT FEVER

RACE WATCH

Two champions from different sides of the tracks add up to 35O.8 mph

ALLAN GIRDLER

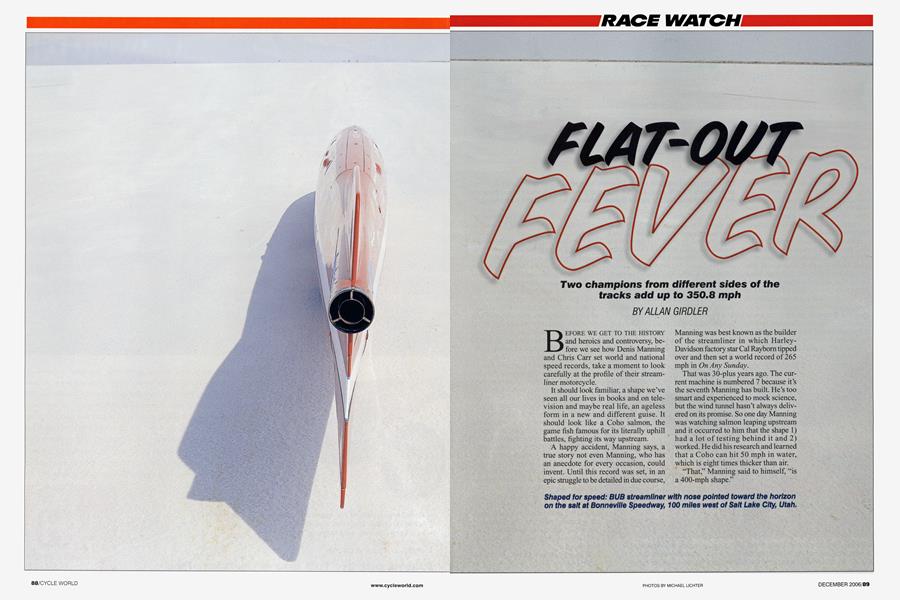

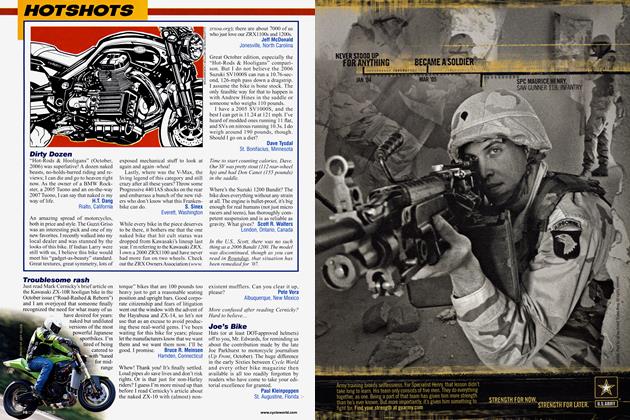

BEFORE WE GET TO THE HISTORY and heroics and controversy, before we see how Denis Manning and Chris Carr set world and national speed records, take a moment to look careftilly at the profile of their streamliner motorcycle.

It should look familiar, a shape we’ve seen all our lives in books and on television and maybe real life, an ageless form in a new and different guise. It should look like a Coho salmon, the game fish famous for its literally uphill battles, fighting its way upstream.

A happy accident, Manning says, a true story not even Manning, who has an anecdote for every occasion, could invent. Until this record was set, in an epic struggle to be detailed in due course, Manning was best known as the builder of the streamliner in which HarleyDavidson factory star Cal Raybom tipped over and then set a world record of 265 mph in On Any Sunday.

That was 30-plus years ago. The current machine is numbered 7 because it’s the seventh Manning has built. He’s too smart and experienced to mock science, but the wind tunnel hasn’t always delivered on its promise. So one day Manning was watching salmon leaping upstream and it occurred to him that the shape 1) had a lot of testing behind it and 2) worked. He did his research and learned that a Coho can hit 50 mph in water, which is eight times thicker than air.

“That,” Manning said to himself, “is a 400-mph shape.”

Thus, when he began work on this motorcycle, he used the Coho profile. Science and technology entered the equation with the body/frame, a true monocoque. Sure, we’ve seen that claim before, usually when someone makes a motorcycle frame of sheet metal.

A true monocoque is an egg, with the shell providing all the structural strength, as it does here. The body shell is a sandwich, layers of carbon-fiber, kevlar, honeycomb aluminum and fiberglass, bonded together and three times thicker (and stronger in torsion) than a Formula One car. There’s a front subframe to carry the front suspension and wheel, and the engine and drivetrain mount to an aluminum plate, while the tailsection, housing the parachute and the exhaust, mounts to the monocoque’s rear bulkhead.

Next really radical feature here is the engine. Check the record books, and all the land-speed record holders have used an engine already on the shelf. Glenn Curtiss made his one-way 137-mph run on a bike powered by a V-Eight he built for aircraft use. NSU, BMW, Harley, Yamaha, Triumph, Indian and Kawasaki used modified production engines for their factory efforts. Ab Jenkins, Sir Donald Campbell, Mickey Thompson and the Summers Brothers ran with car, truck or aircraft powerplants. Even Don Vesco, who holds the current LSR on four wheels, ran with a turbine engine from a helicopter.

Manning’s engine comes from his shop. Once he had the optimum shape for the ’liner-height, width, length, frontal area and so forth-he had to put the rider and the power and the suspension inside that shape. He decided the best way to have an engine that fit was to build his own, a first in LSR history.

By another happy chance, Manning delivered a paper to the Society of Automotive Engineers, and not long afterward an engineer named Joe Harralson showed up at Manning’s headquarters, BUB Enterprises in Grass Valley, California.

He brought with him a design and his ideas, and Manning signed Harralson up, on the spot. The result is a V-Four, included angle 90 degrees, with conventional 90-degree crankshaft throws and firing order. Bore and stroke are 4.125 x 3.42 inches, which works out to usefully smaller than the FIM limit of 183 cubic inches. There are four valves per cylinder, double overhead camshafts, a turbocharger and water-cooling. The turbo, of course, means the pop-off valve can be wrenched down until the engine produces as much power as required. For reliability’s sake, produced power is set in the mid or high 400s at the working peak of 8500 rpm.

The #7 ’liner clearly is a complicated and expensive project. As just one aspect, virtually every part-and there must be more than 15,000 parts-was made only for this motorcycle. Crank and camshafts, pistons and valves, castings for heads and crankcase, on and on through a multi-page parts list, Manning and his team have made just about everything in small lots.

Manning’s original rider for #7 was Rocky Robinson, a skilled racer and licensed Pro and a man of whom Manning always speaks well. But there was some3 contention, and Robinson signed on, as we’ll see with emphasis, with rival team Ack Attack.

Manning put out the word, went as far as the Internet, that he was reviewing résumés from anyone who’d like a shot at the world motorcycle speed record. Chris Carr got the word.

He surely doesn’t need much introduction here, but for the record, Carr has been AMA Grand National Champion seven times and is likely to add to that total. He comes from a racing family, started when he was 6 years old, was known as the Prince of Peoria because he won that national TT there 15 times.

It’s no surprise, then, that Carr watched On Any Sunday when the other kids were reading “The Three Little Pigs” or some such. He especially remembered Rayborn and the Harley ’liner. He and tuner/partner Kenny Tolbert have for several years wondered what sort of bike they could run at Bonneville, but with the proviso that it would be after they’d done their Grand National racing.

Neither did it escape Carr’s notice that while some folks remember wins at Daytona and others recall Springfield, to hold the world speed record puts the rider into another class; everyone with a touch of gearhead knows about Rayborn and Vesco and peers. So he called Manning, and then Carr and Tolbert and the entire Carr family went to see the ’liner and the shop and they came away impressed.

Plus, Carr is an aware and intelligent man, has a good head for business. He’s got major sponsors, Ford for instance, in flat-track and is the best-paid rider in the GN class; he can afford to pay himself more than the Harley and Suzuki teams pay their guys because he wins more than the factories do. Not only that, about 60 seconds after Carr joined Manning’s project, Ford’s new slogan, “Bold Move,” appeared on Manning’s motorcycle and Carr’s fireproof suit. It was, as they say in the movies, the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

Manning has no problem accepting good luck but he doesn’t leave much to chance, so the team took the bike to the salt flats for testing in June, two months before the official meet. This was the tough part, Manning said, because Carr would need to learn how to control the ’liner at low speeds, coasting, in fact, before using the engine.

The first tow, skids down and not much speed, went well. Carr could lean and steer, despite being wedged into the harness, and it was so instinctive, such a trained reflex, that he wasn’t entirely sure if he pushed left to turn left, as one does on a standard motorcycle, or not.

“I just steer,” he said, although later research showed that, with a steering head and a telescopic fork, the ’liner acts like a bike, 1 inch of travel and 10 degrees of steering lock not withstanding. Even so, “If I said I could compare this to anything else, I’d be lying,” Carr noted. “This isn’t like anything else.”

They picked up the tow speed, Carr picked up the skids and then at 60 or so, a wind gust tipped the ’liner to one side. Two months later, the crew still talks about it. The bike snaked to the left and then to the right and headed toward a course marker, but somehow Carr got it under control and came to a stop, upright and unconcerned. How he caught a 45-degree slide with 10 degrees of steering lock and no body English, none of those watching could imagine.

With no harm done, they made another towed run and this time Carr miscalculated the skid release and the bike fell on its side, with damage only to the paint. Straight-faced, Carr said, “I’ve got the crash out of the way and the save out of the way,” which proved to be so.

So they fired up the engine, which is more complicated than it sounds, and Carr took off under power. Take-off was smooth, ditto the upshifts, and the clocks said 150 mph barely off idle. There were issues. The front tire seemed too square, making the steering abrupt, so a car LSR guy was brought in and he rasped off the edges.

Pause here for a major problem, which strikes in force later.

Tires: All the major brands have dropped out of the LSR business. Too much risk, they said, too much liability. Bull. In the 70 years motorcycles have been racing on the salt flats, there have been no deaths. None. Nor any serious injuries. Plenty of riders have fallen off, down or over and skidded to a safe stop. In contrast, riders have been killed and hurt in MotoGP, more so with the earlier 500cc two-strokes, yet at every race the paddock is packed with semis hauling hundreds of tires.

Why the difference? Surely because a win by a tire maker in MotoGP or Superbikes translates into sales, while no sportbike owner will make his tire choice based on Bonneville. What the streamliner crowd has done is first, stockpile every available Bonneville-rated tire they can find, and second, use racing-car tires or sportbike tires or anything with a speed rating that fits or comes close.

Meanwhile, the second major problem from the first test session was a notchy throttle. Carr could not find the delicate touch he’s honed on half-miles and roadracing and any place traction is an issue. The big V-Four would hesitate and then open wide. Something was fighting back.

Linkage, ratios and clearances were checked and found okay, so the conclusion was air power, reacting to the huge single throttle body fitted in the middle of the four cylinders. That was a shop project, so the first practice was closed.

Next try, a month later, the throttles were fine, the salt was dry and Carr ripped off a 300-mph run-in 2.6 of the course’s 11 miles, while deviating a couple of inches off the centerline, on two wheels, at that speed. Manning was dancing with joy. “I’ve dreamed of 300 for years.” And because there were no major issues and the engine wasn’t quite on song and there was no point in risking the equipment, they packed up early and went back to the shop.

“You realize, of course, that this means war!” The quote from the iconic role model, Daffy Duck, introduces another LSR first. Until this year’s bike-only meet, every motorcycle LSR record (and most of the four-wheelers, too) has been set under solo conditions; that is Indian, Harley, NSU, Triumph, BMW, Honda, Yamaha and Kawasaki have scheduled private time, tuned and practiced and prepped in isolation, and run for the record. This year, there were five-yes, five-eligible motorcycle streamliners entered and in the paddock when the meeting opened.

Two, one with Vincent power and one with a Harley V-Twin, did so poorly we’ll leave out names and times. In the running were Manning and Carr with #7, the TOP 1 Ack Attack with two turbo’d Suzuki Fours and the EZ-Hook with a single Kawasaki Four, also turbo’d. This was a civil war, thank goodness, but it was war nonetheless.

The Ack Attack and EZ-Hook are more conventional than the #7, as in tube frames covered with tunnel-tested kevlar, but they both are as carefully constructed and maintained. Ack Attack is the property of Mike Akatiff. Like Manning, Akatiff is an old racing hand. When Manning was running at the drags, Akatiff was building BSA flattrackers for GN star Jim Rice. Manning has his industrial empire, Akatiff heads Ack Technologies.

The strongest emotional issue in this contest involves the rules. Let’s say that Chip holds the world record for the 100-meter dash. His record was set at an international track meet, using certified clocks, which is how records must be set. But one lazy aftemoon Chip and Dale run a friendly foot race in the park, from the lake to the fountain...and Dale wins. Chip still holds the record, but he may not be the fleetest of foot.

Why this little fairy tale? Because Sam Wheeler, owner/rider of the EZ-Hook streamliner, the third contender at this meet, has an odd distinction several times over. At the 2004 BUB meet, Wheeler set fast time with 332 mph, but high winds prevented a return run, so he didn’t hold the record even though he was the fastest motorcyclist ever.

Ack Attack did 338 mph at Bonneville, also not a world record because it was an SCTA meet, so the AMA and FIM weren’t there. And Wheeler had an exit speed of 342 mph-the SCTA has a second timing trap at the end of the measured mile-so he was again the fastestever rider without the record, still held at this point by Dave Campos in the Easyriders ’liner at 322 mph.

The first battle of this war, so to speak, began on the first day of the BUB ’06 meet. Robinson and Ack Attack turned 344.673 mph up the course, 340.922 mph down, and claimed a world record of 342.797 mph, after which they passed the AMA and FIM inspections.

Weather and details kept Manning’s #7 from running until two days later. The plan was to test. “It’s geared for 325,” Manning told Carr as the crew fired the engine. “If it feels good, go to 8500 rpm and hold it.”

It felt good. Carr’s up-course run was 354.832 mph.

“I didn’t know it was a record run,” Carr said happily, “the data said 325.” (The crew later learned they’d miscalibrated the speedometer, thanks to a different front tire.)

The BUB crew turned the ’liner around and 20 minutes later made a return run, 346.937 mph, averaging 350.884 mph, a world and national record, and they, too, passed the inspection. Manning was as pleased as could be but not yet satisfied: “Let’s take this thing back to the pits and put on some more [higher] gearing.”

But wait. When all the fuss had died down, the Ack Attack team had discovered they’d broken part of the drivetrain. The rear wheel has a sprocket on each side, one for the front engine and one for the rear, with a jackshaft and intermediate sprockets to keep the engines in synch, and one of the bearing carriers had broken.

At the #7 debriefing, they made a list: The rear chute had broken its line, the engine never ran smoothly, and worst, the rear tire had chunked some of its tread. Carr wasn’t too concerned. “It’s not the first tire I’ve ever chunked.”

“Yeah,” said one of the crew, “but it’s the first at 350.”

Reflecting on the actual runs, Carr said the return was tougher. There was a side wind and “I was turning left the whole run.” In terms of speed, no comparison: “I’m used to speed on the mile, 130 on a bare bike, in the draft and out of the draft. Here, out of the blast, I can hear the engine but it’s quiet.”

At 360 mph, you’re doing one mile in 10 seconds. Carr has to get the bike under power, shift and read the instruments, see where he’s headed and what the engine’s doing, then roll out, pop the chutes at the right time, hit the brake and drop the skids, again at the right time, all in less than 2 minutes. In brief, Carr said, “I’m too busy to feel the speed.”

The celebrations were mixed with comic opera. Over in the Ack Attack camp, the crew was working on the broken carrier, a CAD-CAM part, but they were a long way from a machine shop and all they had was the equivalent of JB Weld from the truck stop. Robinson said, “We had the record for two days. All we want is to get it back.”

Akatiff chipped in, “Our rider bought dinner after we set the record.. .the steaks lasted longer than the record did.” He came over to the #7 camp and congratulated Manning, adding, “You sure surprised us.”

Manning didn’t reply just then, but he did say later he’d expected more respect than that, seeing as he’d held the record before and Akatiff hadn’t. The crew, feeling much the same, took 6 inches of red duct tape, wrote “Chris ‘Sandbagger’ Carr” on the tape and put it on the side of the cockpit.

And at the EZ-Hook tent, Wheeler was making a decision. His ’liner was designed and built to use a “tireless”-is there a better term?-front wheel. Light metal wheels have been used by the LSR cars since the tire problem developed, but such wheels have never felt right on bikes, Wheeler said, something about motorcycles leaning while cars don’t. He had a wheel and tire he got from Manning, and he was going to try it in the belief that it would be good for at least two runs.

Meanwhile, Manning had another rear tire-two, in fact, racing-only 20 x 4.5 x 15 Goodyear Eagles-but he had only one rear wheel. Kenny Tolbert found this hard to believe. He’s got stacks of spare rear wheels for the flat-track bikes, and he said as much, then someone on the team said it was a question of budget, at which most people in the crowd shook their heads or snorted behind their hands.

Some of the Manning crew headed for the nearest truck stop that had a tire changer, while others checked out details, fixed the chute rope and swapped for a new rear sprocket, one tooth down and giving 365 mph at 8500 rpm. When the wheel and new tire arrived, there was a problem. Tubes in racing are ancient history; but the new tubeless tire had been stored on one sidewall, and the resultant distortion was causing a huge gap between tire and wheel.

How to seal the tire against the wheel? Sounds foolish now, but here was a paddock filled with people who solve problems all day long, centuries of racing know-how...and, swear to God, nobody knew how to do it.

While this was going on, Wheeler took the EZ-Hook to the starting line. The Manning and Ack Attack crews stopped what they were doing, faced the course and went silent.

The EZ-Hook flashed past.

The clocks said 355.303 mph for the measured mile.

The chute came out, but then the bike tipped over and slid to a stop on its side. The news flash said the front tire had blown, but later inspection showed the tire had been shedding rubber most of the run and then the valve had broken, despite the aircraft cap, and the tire had deflated. That was it for this year. Once again, Wheeler had gone faster than the record he’s yet to hold.

After an all-nighter, the #7 guys had the tire seated. Looking like seconds at an old-fashioned duel, Manning and Akatiff agreed to meet on the field of battle, at dawn.

Now, the debate: Everyone present who didn’t have a dime or skin invested in the contest agreed Carr should make an allout pass, just to settle the % issue, to be the fastest and hold the record. Carr and Manning, the true investors in the enterprise, didn’t agree. They’d come for the record, they’d taken the record and they would defend the record.. .if they had to.

So, on the morning of the last day of the meet, Robinson climbed into the Tiner, Akatiff ditto into the push truck. The first try was aborted because the push mechanism fouled and put the bike into full right lock. The second try ended before the traps, with a gust of wind shoving the Tiner off course. The third try ended with engines astray, as the curbside fix failed. Akatiff said that’s it for this year, and Manning put the #7 back in the trailer.

Game over.

There’s another viewpoint. Carr’s family was there, mom and dad, wife Pam, sons Cale and Cameron. Cameron is a little guy. While the grown-ups did whatever they do, he excavated salt, chortling, “I’m digging for gold.” Cale is 9, vitally interested in dad and his job. Cale let it be known that he wouldn’t mind riding along in the Tiner. After the second run, he was asked, “What do you think of your dad’s work?” “Awesome,” he said. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue