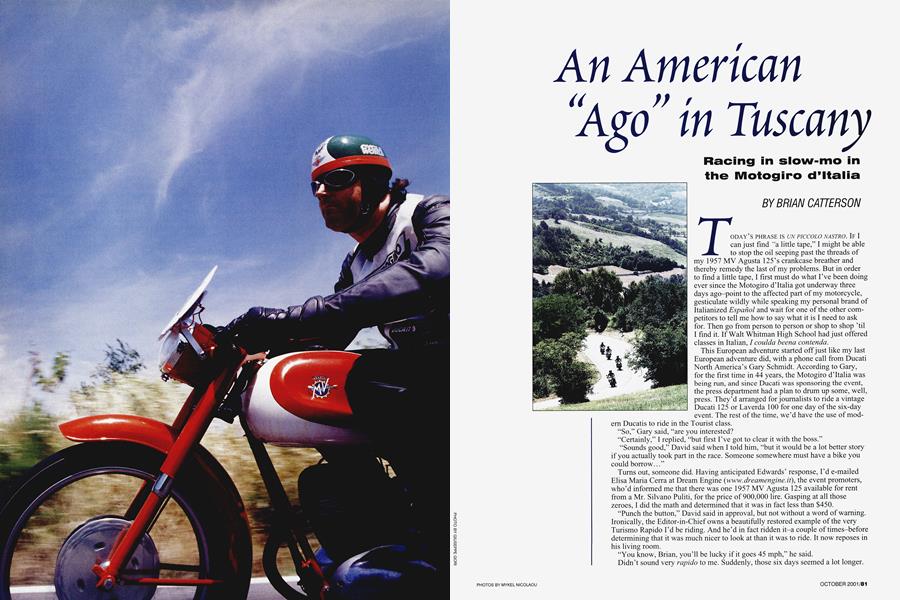

An American "Ago" in Tuscany

Racing in slow-mo in the Motogiro d’ltalia

BRIAN CATTERSON

TODAY’S PHRASE IS UN PICCOLO NASTRO. IF I can just find “a little tape,” I might be able to stop the oil seeping past the threads of my 1957 MV Agusta 125’s crankcase breather and thereby remedy the last of my problems. But in order to find a little tape, I first must do what I’ve been doing ever since the Motogiro d’ltalia got underway three days ago-point to the affected part of my motorcycle, gesticulate wildly while speaking my personal brand of Italianized Español and wait for one of the other competitors to tell me how to say what it is I need to ask for. Then go from person to person or shop to shop ’til I find it. If Walt Whitman High School had just offered classes in Italian, I coulda beena contenda.

This European adventure started off just like my last European adventure did, with a phone call from Ducati North America’s Gary Schmidt. According to Gary, for the first time in 44 years, the Motogiro d’ltalia was being run, and since Ducati was sponsoring the event, the press department had a plan to drum up some, well, press. They’d arranged for journalists to ride a vintage Ducati 125 or Laverda 100 for one day of the six-day event. The rest of the time, we’d have the use of modem Ducatis to ride in the Tourist class.

“So,” Gary said, “are you interested?

“Certainly,” I replied, “but first I’ve got to clear it with the boss.”

“Sounds good,” David said when I told him, “but it would be a lot better story if you actually took part in the race. Someone somewhere must have a bike you could borrow...”

Turns out, someone did. Having anticipated Edwards’ response, I’d e-mailed Elisa Maria Cerra at Dream Engine (www.dreamengine.it), the event promoters, who’d informed me that there was one 1957 MV Agusta 125 available for rent from a Mr. Silvano Puliti, for the price of 900,000 lire. Gasping at all those zeroes, I did the math and determined that it was in fact less than $450.

“Punch the button,” David said in approval, but not without a word of warning. Ironically, the Editor-in-Chief owns a beautifully restored example of the very Turismo Rapido I’d be riding. And he’d in fact ridden it-a couple of times-before determining that it was much nicer to look at than it was to ride. It now reposes in his living room.

“You know, Brian, you’ll be lucky if it goes 45 mph,” he said.

Didn’t sound very rapido to me. Suddenly, those six days seemed a lot longer.

Originally held as a bicycle-style stage race, where the objective was to get from Town A to Town B as quickly as possible each day, the Motogiro was revised for its revival, so that it’s now a regularity run. Think ISDE, only on pavement. But the mechanical requirements remain faithful to the original event: Eligible bikes must have been manufactured prior to 1957, the last year the race was run, and could displace no more than 175cc, with a sub-class for 125s in which I’d be competing. Total distance for this year’s Giro, which means “lap” in Italian, was 832 miles, or about half as long as the original race.

For weeks prior to my departure, I made co-workers jealous by reading snippets from the event itinerary. Day Two contained my favorite passage: “The Motogiro Village is located near the stands of the yachting event ‘Blu Rimini,’ where a discussion will take place involving figures from the motorcycling community and the yachting world.” Can’t get enough of those yachting events, myself. The other days made mention of visits to private automobile and motorcycle collections, medieval hamlets, a waterfall created by the Romans and a gala awards dinner at a castle. Even if the riding was miserable, the parties would be fabulous, and it was in Italy, so you knew the food would be good. Say, where did I put my passport?

The race was scheduled to start at the Ducati factory in Bologna at 1 p.m. on Tuesday, June 5th, so the organizers arranged for all us renters to meet there on Monday afternoon. My little MV looked to be in pretty good shape, and after trading money and paperwork, Mr. Puliti bade me to take it for a test drive. I did, and was pleasantly surprised to find that it worked as good as it looked. With something like 7 horsepower on tap, acceleration was about on par with a Honda XR100, but the engine ran well, shifted smoothly and all the controls worked-including the right-side, downfor-up, heel-and-toe shifter, which despite my fears ultimately proved to be second nature.

As I prepared to stop, however, I realized that I’d neglected to use that “other” foot control, the left-side rear brake pedal.

So I stepped on it, and heard a horrible snap, clank, wup-wupwup! Looking down, I was horrified to discover that the brake rod had snapped and wrapped itself around the rear axle!

Puliti speaks very little English, but I could tell from his reaction that this was a Big Problem. You don’t just nip down to the comer shop for old MV parts, even in Italy. But we needn’t have worried, because for the first of many times this week, I was rescued by Riño Carrachi, who the organizers had hired to drive the chase tmck and assist in just such mechanical endeavors.

Realizing that I was American, Carrachi introduced himself by saying, “I was Doug Polen’s mechanic.” Which he was. But as any Ducatista worth his sea salt knows, Carrachi is also the C in NCR, as in the firm that built those lusty bevel-drive V-Twin racers all those years ago. And which last year sponsored American Ben Bostrom in the World Superbike Championship. Anyhow, with the considerable resources of the Ducati factory at his disposal (they make motorcycles there, you know), Carrachi managed to straighten and re-weld the brake rod by the next morning.

Milling about the parc ferme before the start, I watched a television crew interview Leopoldo Tartarini, boss of Italjet, one-time factory Ducati racer and winner of the 1953 Motogiro on a Benelli. Globe-trotting Euro-scribe Alan Cathcart was asking the questions in English, so I eavesdropped shamelessly as Tartarini recalled his experiences in the old Motogiro.

“The police did a good job controlling the roads in the north,” he said, “but in the south it was impossible, with tractors and ‘beef in the road.” By beef, I assume he meant cattle, though from his description of one of the accidents, it might have been more grisly. “In 1955, near Rome, we had six riders dead in one day. Six!”

Cathcart, who researched Motogiro history for his book Ducati Motorcycles, dismissed Tartarini’s tale as hyperbole, saying that while there were indeed many accidents, there are no records of fatalities in 1955. To the contrary, he claimed the only deaths occurred in the Giro’s original iteration, during the period 1923-26. Not that it mattered,

because it was spectator deaths in the car-racing equivalent, the Mille Miglia, that ultimately forced the Italian government to ban open-road racing.

While Tartarini didn’t compete in this year’s Motogiro, two former event winners did. Remo Venturi, the 1957 victor, rode an MV 150 Rapido Sport-the only other MV in the event-while 1956 winner Giuliano Maoggi shared the journalists’ Laverda 100.

Soon the riders’ meeting got underway, with Direttore di Gara Paolo Rossi explaining the rules in Italian, after which the flamboyant Max Stohr translated them into English for the one British and four American competitors on hand. Unfortunately, when Max had finished speaking, I still had no idea how the scorekeeping worked. And when I cornered him, he admitted that he didn’t get it either.

“They handed me something to read, and it didn’t even make sense in Italian,” he said.

“There’s no way I could explain it in English!”

Add to this a confusing scorecard with various acronyms denoting the various types of timekeeping sections, a magazine-sized road book that we were somehow supposed to read while riding and tiny red-andwhite route arrows taped to the odd road sign, and I just knew I was going to get lost.

I did, too, a couple of miles from the start. But just as I was about to hang a U-tum, I spied the race director’s car coming the other way, with a bunch of bikes in tow. I was number 11, which means I started on the sixth minute, and it seemed the 10 riders in front of me had all made a wrong turn. Jeez, what would the next 830 miles be like?!

Not that bad, it turned out, because after this initial glitch, the route was actually pretty easy to follow. And the pace wasn’t that quick, so if you suspected you were lost, you could just wait by the side of the road for the riders on the next minute to come by-or not-and still arrive with time to spare.

In theory, I could have just stuck with the other rider on my minute, but number 12 Mauro Soldani’s Mondial 125 Sport expired, which meant I had to start alone for the rest of the week.

When I did start, that is, because my troubles were piling up faster than 125s at a wet Grand Prix. At the very first checkpoint, the kickstarter snapped off. All the chrome in the world can’t make 44-yearold potmetal any stronger. And while I had no problem bumpstarting the little Single at the second check, it refused to fire at the third, prompting my first ride in the chase truck. There would be others.

Unfortunately, my little MV suffered terminal points meltdown, which Carrachi said couldn’t be repaired until he could get new parts in Rimini two days hence. So on Day Two, Wednesday, the organizers gave me a brand-new Ducati 900SS to ride with the Tourists, who despite being mostly on modem machinery actually moved slower than the vintage racers. Which was fine by some, notably the ever-smiling John Shaw, who brought his 1929 Panther 500 over from Scotland, and his friends Neil and Ann Cowan, who brought their 1960 BSA Gold Flash 650. Not to mention the affable giant Ugo Bottom, whose 1954 Güera Saturno 500 was too big for Giro mies, but who rode like he was racing anyway.

The snail’s pace was making me miserable, however, and my mood grew worse when it began to rain-fortunately for the only time during the week. So I was relieved to leam the following morning that Carrachi had managed to replace the MV’s points and kickstarter, and I’d be able to start.

Misfortune soon stmck again, however, and I didn’t even get out of town before the MV started to sputter and cough and generally refuse to accept anything over part-throttle.

The bike’s neat little toolbox proved empty, so the only thing to do was sit by the side of the road and wait for the tmck.

The driver and I made a feeble attempt to diagnose the problem at the first check, after which further repairs were mied out by the fact that American Vicky Smith borrowed my bike’s sparkplug cap to keep her Motobi 125 running. The organizers gave me a Monster 750 to ride this time.

After looping into the hills near Sansepolcro to the west, we spent a second night in Rimini. As I was dressing for dinner, Kristin Scheiter of Dream Engine called to ask if I could come downstairs. Carrachi had diagnosed the MV’s problem as a too-low float level, and wanted me to take the bike for a long ride to ensure that it would keep running. If it didn’t, they were going to put it in the truck permanently, whereupon Puliti would give me my money back.

I rode the MV the length and breadth of Rimini, and the little engine was... well, if not singing, at least humming. So on Friday morning, Day Four, I was back in the race. By this time I was ranked dead-last in the standings, but in the spirit of participatory journalism resolved to do my best for the remaining three days. Only problem was, the MV’s speedometer and odometer didn’t work, and my timekeeping equipment consisted solely of my wristwatch!

Still, by taking cues from the riders on the minutes ahead of me, I began to understand the scorekeeping, and actually started to zero checks. In fact, I was only assessed penalty points today when I lost time at a self-serve gas station (don’t ask) and spent too long re-fueling my weary body at lunch. Love that antipasto!

This was the longest day of the race, the distance from Rimini through Ancona to Temi encompassing 188 miles. That’s a long way to go on a 125 even on flat ground, but we climbed up through mountains, above timberline to Castelluccio, a walled city in a setting so idyllic it seemed as if it was plucked from a fairytale. Riding high on the mountaintops, we looked down at the valley below to see giant grids of wildflowers in every color of the rainbow. And to hear the locals tell it, we’d missed the peak of the bloom by a couple of weeks. I couldn’t imagine it looking any lovelier.

We had a lot of time to admire the scenery, too, so slow were our little machines going uphill. The Italians used to call tiddlers “donkey bikes” because of the sound the engines made as they were held wide-open and repeatedly shifted from first to second and back. Eeeee-yooore! Eeeee-yooore! At times, I was tempted to walk.

Going downhill was a different story, however. Weighingin at a tick over 200 pounds, my little MV flicked in and railed comers like a racebike. The suspension was surprisingly well-sorted, and once I’d learned to tmst the repaired rear brake rod, the binders actually hauled the bike down from speed quite effectively. Tucked-in for all I was worth, close to 70 mph was possible on long descents.

As evidence of that, I was the first rider to arrive at the checkpoint in Noreia, which is where I found myself looking for un piccolo nastro, the shouldered rim of my rear

wheel having filled with flung-off oil. I found it in a dmg store in the town square, paying 2000 lire-about a dollar-for the remnants of a roll of brown electrical tape. But it did the trick, and from that point forward, the MV was bulletproof. Well, aside from the hom falling off, that is...

By this time, my fellow competitors were warming up to the funnylooking American in the Davida Agostini-replica helmet, and a few revealed that they spoke rather good English. Most of the riders were older gentlemen, age 50-plus, but two of them, Simone Piersanti and Luca Quintili, were younger than me, and we became fast friends. Simone and his Motobi 125 were one of the quicker combinations in the competition, regularly smoking past me on the straights, while Luca and his twostroke Mi-Val-the “other” MV, .sort of an Italian copy of a DKW-saved me from making a wrong turn on more than one occasion.

It was while we were in Norcia that one of the Italians I’d passed going downhill christened me “Kenny Roberts.”

I looked at him, pointed to my helmet, and said, “No, today I am Giacomo Agostini.” To which he replied, “Yes, if they cut you off at the knees, you would be.” Everyone laughed, and from that point forward they all called me

“Ago Grande A

Throughout the event, each municipality we visited greeted us as though the Motogiro was the biggest thing to happen there in years. And maybe it was. Every time we arrived at a checkpoint in some town square, the locals poured out en masse, laying on a colossal buffet and dispatching the prettiest girls in the village to serve refreshments. Gas-station attendants lined the curbs in their matching red jumpsuits and waved handkerchiefs as we flashed past, and a few villages pulled out all the stops and had their local folk groups perform. Collescipoli’s was Kaleidoscopic!

But it was on the final day that I got the strongest sense of what it must have been like to compete in the original Motogiro. Motoring through a right-hand sweeper in a town called Dicomano-which as far as I can tell means “talk with your hands”-I spied a little old man dressed in his Sunday best. As I drew near, he took a step toward the curb, raised his hands to form an “A” above his head and visibly trembled as he hollered at the top of his lungs, “Aaa-gooo-steee-neee! ”

Senility might be underrated, I thought to myself as I gave him a little wave. If I brightened some senior citizen’s day by making him think he saw “Ago” race one last time, well, I think even Giacomo himself would forgive me the impersonation.

The final leg of our journey returned us to Bologna via the Futa Pass, where I came across two riders on modem MV Agusta F4 750s going the other way. They both waved, and I recognized the one in the red jacket as none other than the F4’s designer, Massimo Tamburini. Three days earlier, some of the Tourists had reported running into him in the hills west of San Marino, and now here he was again.

I spent a few minutes riding back and forth across a scenic bridge for photographer Giuseppe Gori’s camera, and when I took off again, who should ride by but Remo Venturi on the other MV! When he stopped for gas, I pulled up alongside and suggested that perhaps the two MVs could cross the finish line together. Which we did.

That night there was the gala awards dinner at the Panzano Castle in Modena, which housed what must be the world’s largest collection of vintage Fiats, no small number of Güeras and a prototype I recognized as the one-and-only turbocharged Moto Morini auctioned off last year at Sotheby’s. Everyone put on their best threads, and the organizers handed out fabulous trophies made from engine parts. The big winner was Alfio Sorgata, who on his 1956 Morini 175 managed to drop just 1 minute and 59 seconds over the course of the six days. For his efforts, he received a one-off Ducati Monster 600 painted up as a Gran Sport 100, the bike on which Ducati first tasted success in the Motogiro.

Topping the 125cc class in fifth place overall was the 1956 Morini 100 of Silvano Fabbri, ironically one of the riders I’d been cueing off of at the checkpoints. Good call. And while I wound up a dismal 49th out of the 52 competitors, more than 5 hours behind the leader, I took solace in the fact that I finished sixth on the final day. If my little MV had worked this well at the onset, I really could have been a contender!

Watching the fireworks after dinner, I chatted with Richard Weedn, a Santa Barbara resident who deals in exotic bikes and cars. Richard was the highest-finishing American in the event, riding his Bianchi 175 two-stroke to 37th place, and he’d clearly been bitten by the bug. “I’ve been talking with the organizers, and they like the idea of doing a Motogiro di California,” he said.

I like it, too. If nothing else, I already speak the language.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue