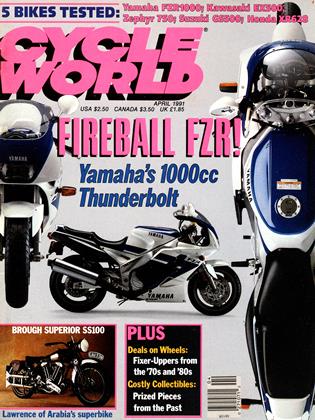

SIMPLY SUPERIOR

A superbike in 1938, a $70,000 classic today

DAVID EDWARDS

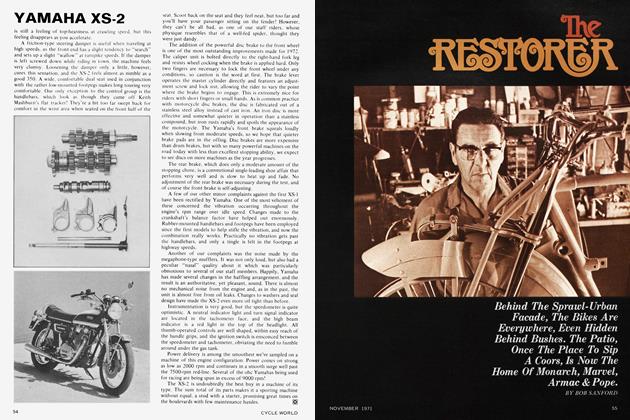

I KNOW WHAT KILLED COLONEL THOMAS EDWARD Lawrence. You remember enigmatic T.E. Lawrence, the famed desert raider who led the Bedouins to spectacular victory against the Turks in 1917, the title subject of the epic, Oscar-winning 1962 motion picture Lawrence of Arabia, the long-time motorcyclist who died in 1935 after crashing his beloved Brough Superior on an English country road.

The exact cause of the accident remains veiled in mystery to this day, with everything from suicide to rider error to some elaborate conspiracy blamed for the death of the man Sir Winston Churchill called “one of the greatest beings of our time.”

Well, I’ve just come back from riding a Brough Superior, and if Lawrence’s was anything like the SS 100 model I was astride, the great man was killed because he didn’t have any g.d. brakes!

I arrived at this realization abruptly, a few spirited turns into a crooked backroad, with a rear drum overheated to the point of uselessness and a front brake juddering as it, too, gave up the ghost. From the centerstand shavings I’d left in the previous corner, I knew the Brough’s limited cornering clearance wouldn’t allow me to scrub off speed by pitching the bike hard over, and while I was in no danger of an untimely demise, the view over the SS’s bulbous, nickel-plated fuel tank was definitely beginning to get interesting.

Safely, if not surely, through the corner, I pulled into the next turnout to allow the hubs—hot enough to raise welts—a few minutes of cool-down. I was reminded of the comment attributed to English auto maker Herbert Austin, who responded to criticisms about his early cars’ atrocious stopping properties by saying, simply, “Good brakes encourage bad driving.”

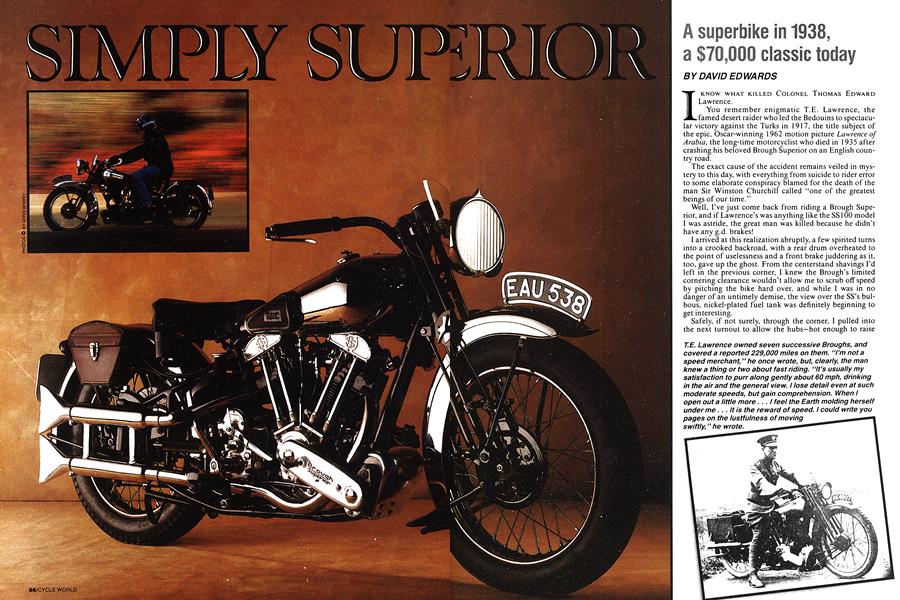

As the binders cooled, I stood back and let my eyes meander over the shiny Brough. (For the record, the pronunciation is not “Bro” or “Brog” or “Brow.” Say “Bruff,” as in rhymes with “tough.”) There was a lot to take in, as Brough Superiors were very much pieced-together affairs, depending on an assortment of suppliers. This particular SS 100, a 1 938 model, used an engine built by the AMC company, the lOOOcc V-Twin virtually identical to those installed in some AJSs and Matchlesses. The separate gearbox is by Sturmey-Archer, a four-speed, footshift unit. The ignition system, curiously mounted in front of the frame’s downtube, came from Lucas. The frame, plunger-suspended at the rear, was mated to a Castle fork (advertising motto, “The Speedman’s Ideal”), an exact copy of the Harley-Davidson leading-link fork. Those horrid excuses for brakes were furnished by Enfield.

Despite this hodge-podge approach, the Brough managed to be a machine of sublime beauty. In particular, notice the grace of the exhaust system, sweeping from the cylinders and climaxing in dual, cast-aluminum fishtail tips. Classic or modern, this may be the most handsome motorcycle ever built, proof positive that a bike need be adorned with little else other than chrome, black paint and gold pinstripes.

Usually on display at the San Diego Automotive Museum, this SSI00 had been graciously offered to me by its owners. Art and Bob Bishop, father and son. who are very active in the Southern California classic-bike scene. My first attempt to ride the Brough ended with clutch trouble. That fixed, two weeks later, my second effort was interrupted after but a few miles by an overflow problem with the carburetor.

Undaunted, Bob delved into the Amal’s innards. “Well, I can tell you one thing: This is probably the only SS 100 in the world right now with a warm engine,” he said, patting the burnished metal of the old bike’s crankcase. It's an ironic fact that not many Brough Superiors—perhaps the ultimate roadster of the 1930s—get ridden on the road these days, as they’ve become just too valuable. The Bishops, who purchased the SS 100 at an estate sale in England for what Art allows was “a very good price,” estimate the replacement cost of their bike is now $70,000.

“As time goes by, we’ll take it a little easier,” said the elder Bishop. “You really don't want to wreck something this rare.”

Built in Nottingham. England, from 1919 to 1940 by company owner George Brough, the brand was advertised as “The Rolls-Royce of Motorcycles.” Manufactured to exacting standards, no two of the high-priced sporting machines were alike, as customers chose from an array of options and specifications. This led to an affinity between man and machine, and many owners nicknamed their Broughs. Lawrence christened his bikes “George I” through “George VII.” Other well-known monikers included “Spit and Polish.” “Leaping Lena,” “Moby Dick” and the “Karbro Express.” Brough called one of his personal mounts “Old Bill.”

Each bike was completely assembled before painting and plating, double-checked, then broken down and reassembled. A total of 3000 Superiors left the Haydn Road works before World War II put an end to the marque, fewer than 400 of that number being SSI00 models.

Each SSI00 was certified as capable of 100 miles per hour when it left the factory, an astounding figure 50-plus years ago. High performance, in fact, was a driving force behind the company, as typified by the Brough’s many race glories. George Brough himself was an avid sportsman, amassing an impressive total of more than 200 trophies and awards, though “Old Bill” twice suffered tire blow-outs and spit Brough to the ground in excess of 100 mph. A supercharged model even held the world’s speed record at 169.7 mph for a time, although its rider, Englishman Eric Fernihough, was killed on the bike in 1938 trying to up the mark to 180.

After resuming my ride on the Bishops’ SSI00. I indulged in a smaller-scale speed run of my very own. The Smiths Chronometrie speedo registered 80 mph before discretion—and the thought of scattering the 53-year-old powerplant—slowed me down. At 60 mph. however, the Superior felt as solid and stately as the Houses of Parliament, with a restrained but muscular melody flowing from the twin fishtails. Vibration at that speed was minimal. It's easy to see how T.E. Lawrence knocked off repeated 500to-700-mile days with his Broughs.

In his pithy history. The Rolls-Royce of Motorcycles, English writer Ronald H. Clark writes ebulliently about an AMC-engined SS 100 much like the one I rode, noting, “It looks so right that it would be difficult to fault the position of any item ... Its lines will never become dated.” Clark goes on to say that the sight of a Brough Superior “never fails to inspire me and gladden my eye.”

After a glorious morning aboard one. I second the motion. Had I to nominate one motorcycle to go into a time capsule for future generations to unearth, George Brough’s passion-built SSI00 would be my choice.

Bad brakes and all.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontBusiness As Usual

April 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargePas-De-Deux On Pine Avenue

April 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsStaying Hungry

April 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1991 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Italian-Japanese-British-Swiss-Kiwi Connection

April 1991 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Great Guzzi Buy-Out of 1991

April 1991 By Jon F. Thompson