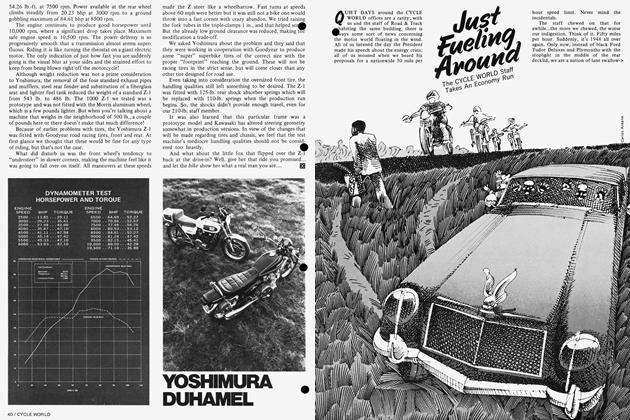

Yamaha TA-125 Road Racer

With One Of These Screamers And $1647, You Too Can Be a Boy Racer ...For At Least A Year

John Waaser

YEARS AGO, the Norton Manx was “King of the Isle,” and Matchbox was more than just a line of toy cars. Matchless, Norton’s poor stepbrother in the AMC combine, produced a road racer similar to the Manx, but a bit less sophisticated.

Known as the G-50, in typical Matchless letter-number fashion, the bike was furnished in a slightly lower state of tune than the Manx, and used a single, chain-driven overhead camshaft, rather than the Manx’s tower-shaft-driven double knocker setup.

The Matchless G-50 was preceded by the AJS 7R, from which the G-50 was developed. The 7R was produced in 1947 as a racer which would be easy and cheap for the average rider to maintain. With a displacement of only 350cc, it was slightly slower than either of the 500s; just right for the fainthearted road racer who couldn’t feature zipping down Bray Hill at a buck fifty or so. It also cost quite a bit less, and it proved to be less dear to maintain through a season of racing. Officially designated the 7R, it quickly earned an affectionate nickname—“The Boy Racer.”

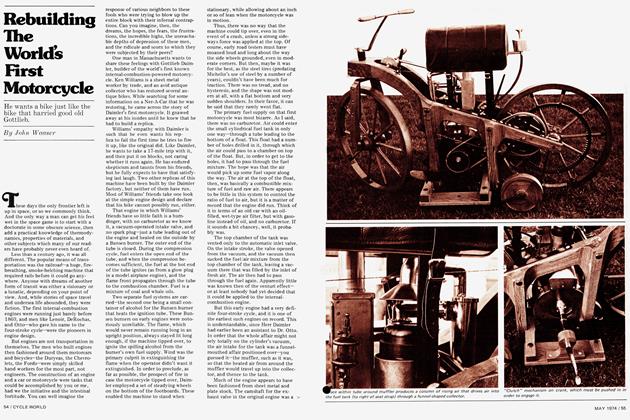

Yamaha in recent years has become the undisputed leader of the 250cc class in American road racing, and hasn’t done too badly in the open class, either, in spite of a large displacement handicap. And now, quietly, Yamaha has introduced a new Boy Racer-a bike which sells for less than a grand (to the dealer), can be raced most economically throughout the season, and which is fully capable of doing in even much larger competitive mounts. At the Pocono road race this year, for instance, young Dana Dandeneau hopped on his TA-125 in his first AMA road race and walked away from the pack. And that was a combined race of up to 200cc bikes.

Bob Fairbairn works for Boston Cycles; he confiscated one of the firg| examples of the breed to come into th™ area, and proceeded to race it in AAMRR (the eastern Alphabet Club) events.

Bob also is a road racing freak. So is his boss; so, it was arranged that Bob would have a day off to take the bike and this nervous novice up to Bryar Motorsport Park for a day of play on the machine.

We arrived at Bryar with half of Boston Cycles service department, the TA-125, a 350 waterpumper, a 350cc Kawasaki cafe racer Triple and a 750cc BMW. The 125 looked like a boy’s motorcycle in that company, and out on the track it was the only one of the four which wailed. I mean there was no doubt just which bike was headed your way, even with earplugs.

• After Bob warmed the 125 up, I was cased in protective leathers and loaned a Bell Star, in preference to my shieldless Magnum. The bike was ready, and I thought I was; after all, do I not have Tomaselli clip-ons on my street bike?

I snicked the boy racer in gear, and released the clutch. So far, so good. As I got moving, I picked up my foot, and attempted to place it on the peg. I couldn’t. Me, 5 ft. 4 in., and shortlegged at that, who fits so well on the 250 Yammie; no way would my leg come up into what Bob described as the “semi-fetal position” necessary to ride this little tiddler. I stopped and tried again, this time using my right foot to prop the bike up while stopped. It worked; a second later we were touring the course.

The pavement is deteriorating badly of late, and cars had laid a cover of oil and rubber on top, which didn’t help traction. I decided that discretion was the better part of valor, and took a half-dozen easy laps before coming in to see if the controls could be arranged to better fit my bod. I was having a great deal of difficulty getting my feet on top> of the shift and brake levers.

Riding a bike with a 13,000 rpm red line doesn’t upset me much; my street bike has a five-figure red line. But the narrow powerband, coupled with an uncommon willingness to exceed the red line, keeps you busy until you get used to the feel of the engine and know where to shift pulling into and out of each corner. What will really set you free, however, is riding a bike which will bog, and almost die, when you crank the throttle on at eight grand in second gear. Now that’s a completely foreign experience to most of us!

The shift pattern is Early Japanese Reversed—that is, one up, and four down, on the left. The reverse is due to the linkage.

The controls were adjusted to their limits already, and Bob says the only thing to do was get used to them. From

my experience with fitting clip-ons to my street bike, I know that the body can make these adjustments in time, but it was becoming more obvious that this bike was a “boy racer” in a much more literal sense than was the 7R.

Other than the controls, the bike felt delightful. Handling is quick; but the bike still felt stable at the speeds I was going (over 100 on the straights, very slowly in the turns), and the brakes were superb. The engine was smooth, and, as long as you kept it in the power band (10,500 to 12,500 rpm) it was most impressive for a 125.

From Loudon, it was out to lunch, then back to Boston Cycles for a minor teardown, and a look at what it costs to go racing. Yamaha brought about 400 of these modern-day boy racers into the states this year. It is obvious from the price that the bike must be derived essentially from stock components—and a quick look will confirm that the frame and engine appear to be stock lOOcc LS-2 street bike parts—the frame even

has the center stand lugs still on it.

Even things which are different are the same; the brakes, obviously, are not LS-2 items—but they do look familiar. They’re lifted straight off Yamaha^ 200cc road burner, with racing linings installed. Light in weight, and powerful enough for the machine’s weight and speed potential, they worked superbly on the track. The swinging arm is also from the 200cc machine, for a little more rigidity out back.

If you look really carefully, though, you can see a small difference in the frame. The top rear frame tubes on the LS-2 form the subframe only; they don’t run up to the steering head. Those on the road racer run up to the steering head for more rigidity. The engine’s bottom end is so close to stock LS-2 that it takes a parts manual to show the differences. One gear ratio is different, and a racing crank is used, with two more rollers, and racing rods which have bigger slits for oiling, silver bearing cages, and more side clearance. Even the cases are stock, and autolube is included.

The top end is strictly racing, with singie-rmg pistons, chrome-plated bores, trick porting, and racing carburetors. The ignition coils and “black box” are the same as on the 250cc and 350cc road racers, but the donor is a special double lead type, said to give off fewer stray sparks at the higher rpm this engine thrives on. The new 700cc Four will require a double lead donor, and Bob thinks the hot setup might be to use it on the medium-weight bikes, also. The ignition has proven quite reliable.

Other changes are the obvious ones— tank, seat, fairing, tachometer, rims and tires. The package is good for almost 50 mph in top speed over the LS-2, which will run about 73, flat out.

Use of so many stock parts creates some hassles, though. The engine design is not as modern as the larger bikes; the cases split vertically. You must have the proper tools for changing the crank, otherwise it will never go in straight. At the speeds this engine turns, out-ofround tolerances on the crank become important. Another stock part ill-suited to racing use is the wet clutch. Wet clutches tend to stick together at high rpm, and might just refuse to free immediately in the event of an impending seizure. When you hear that tell-tale tinkle from the engine, you hope your reactions are fast enough—and for sure you don’t want the clutch hanging up.

But it is amazing just how good a racing bike Yamaha has been able to develop using stock off-the-shelf parts. And nobody can deny the cost advantages of this system. With this machine, a youngster can get started in road racing for about the same money as a competitive motocrosser, and maintenhigher, either. Initial cost varies according to the dealer. If a rider is good enough, or the dealer anxious enough, you might get the bike at cost. If not, most dealers charge from $1200 to $1500 for the bike, without a fairing. The fairing is $105, dealer cost. Japanese racing tires are fondly referred to as rim protectors. They will have to be replaced for any serious racing, with Dunlops; dealer cost is about $40 there.

(Continued on page 98)

Continued from page 46

If you’re really starting from scratch, figure $200 or so for leathers, boots and helmet, and you may need a trailer, if you have no other way to transport the bike. At most, if you buy everything in the same place, it should cost you $2000, starting from ground zero. Dealer cost on even the air-cooled 250cc road racer alone is well above tl^^ figure, so the TA-125 offers chd^P racing indeed.

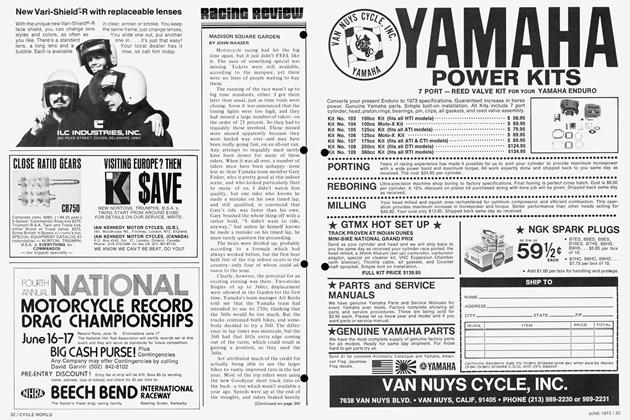

You’ll have to do a minor top end job between each race. This will involve two rings, at $4.15 each, wrist pin bearings (same as the street bike) at $2 each, two wrist pins at 65 cents, four clips at 10 cents each, two base gaskets at 15 cents, and two head gaskets at 35 cents each. You’ll also want to change the transmission oil between races; oil is cheap, so buy the best SAE 30 automotive oil you can. Every second race, figure on replacing the pistons, too, at $11 each. All these prices are retail.

If you should be unfortunate enough to score a barrel, it will zing you $60, but you have to be pretty ham-fisted to do that, says Bob. The crank is good for about eight races, and costs the dealer $47. On parts like this, the markup can be high—as much as double the cost pJ^ 10 percent. Clutch plates should replaced with the crank. If you have the facilities, you can rebuild the crank and save a few bucks there. Bob has run the season on one crank, with a rebuild, and will replace it over the winter.

Bob says the tires should last all year. You might want to replace them before that, since any good tire will harden as it gets used. At any rate, tire mileage will be very much better than with the big bikes. He says the 428H chain will go all year if it is well maintained. Sprockets are steel, and since you will carry two or three of each for gearing changes, they should go the year also. Rear sprockets are $11, retail, while countershaft sprockets are $4.50. Stock shock absorbers are not so great, and a new set on Bob’s bike lost their damping in three races. They retail for $80 a pair. A

A careful accounting of expenses the year for Bob came to $1647 and change, at net prices, excluding such things as spark plugs and oil used at the track and not recorded. Getting a sponsorship for an unknown rider may be

Éfficult, but many dealers are offering a mtingency award program. Last year Boston Cycles awarded contingency prizes to scrambles riders, and Mark Robillard, virtually unknown at the beginning of the year, collected about $1500, at $25 per heat win, $50 per overall win, and $500 for a class championship. Such a system awards a good, new rider right away, without saddling the dealer with a dud; Boston Cycles will be extending this program to certain classes of road racing in 1974. Many other dealers can be expected to institute similar programs, which, combined with the low initial cost of this machine, and the high resale value of a well-maintained bike, could well make racing a break-even venture.

As mentioned, you’ll want to remove the rim protectors from the new bike, and add a fairing. But as with any new ad racer, there are things you can do side which will help, also. Bob likes to undercut the driven gears for positive engagement inside the transmission. The rest, he says, is all careful assembly and liberal use of lock-wiring to make sure parts don’t fall off. Building reliability is important to the privateer, and while the fastest bikes have been slightly modified, he recommends leaving the bike stock for the first eight races or so.

Gearing, jetting, and ignition timing are really critical on this machine, and he suggests you learn to get these spot on before doing any modification. He reports some piston holing, even in stock form, especially if the machine is lugged down to eight or nine grand. There’s a lot of detonation, also, and the spark should never be advanced more than 2mm BTDC. Everything happens quickly with the little tiddlers;

flere isn’t much warning of a seizure, nd if you seize, or scrape a peg, there’s no warning at all of the impending damage to your backside. “One minute you’re driving along, the next minute your hands are empty,” was the way he put it.

The fast guys all remove the autolube system, and run a gas/oil mix in the tank. For one thing, the rear tire tends to scrape through the oil line leading from the oil tank (in the back of the seat) to the pump—and that is good for a certain seizure, if you don’t go down first from the oil on the tire. Bob also warns about some bogus information in the manual; for instance, the book says cylinder head bolt torque should be 16 ft.-lb., when any fool knows that the bolts used won’t stand more than 75 in.-lb. reliably.

The bike is a little sensitive to air gap tthe CDI donor. Anything below 012 in., the rotor will touch the donor. So Bob uses that as a gauge. the gap at 12 thou, and if they touch when the crank gets to whipping at high speed (it leaves a tell-tale mark on the rotor) you know you have one race left on that crank. Lightly sand the marks off the rotor so you can tell the next time it touches. While the tach is redlined at 13 grand, Bob says 14,000 rpm can be used if it’s a question of making it into or out of the corner ahead of somebody you’re dead even with. He doesn’t recommend it as a constant practice, however.

(Continued on page 102)

Continued from page 99

Modifying the engine slightly will net an increase of one to two horsepower. Modifications include cylinder head squish area shape, cutting and shaping the bottom of the pistons, altering the ports slightly, smoothing the ports for better flow, and cutting grooves in the pistons to hold oil for better lubric^^ tion. A few racers find the brand of oi^r is critical, also, as some of the synthetics will drop the rpm range considerably; Bob likes Castrol “R.” If all this sounds like a lot of work for a few extra horses, it is. But Bob is running a 3.00-18 KR96 rear tire; something the stock engine just will not pull. He thinks that gives him an advantage, too.

The swinging arm rubber bushings should be replaced for maximum stability. Frank Camillieri is tooling up to make a swinging arm out of 1 x IV2 in. rectangular tubing. It will have metal bushings, and will be set up to accept Koni or Girling shocks at the rear, which the stock swinging arm will not. In view of the shock problems encountered, this swinging arm should be a good investment, at about $100. Bob also is thinking about shortening the tank to move the seat forward, to hej^^ the seating position a bit, as well as pr^^ more weight on the front end. He reports the front end feels light on occasion.

The motorcycle should be exactly the same for 1974 (we rode a 1973). Bob keeps dreaming about a six-speed, water-cooled, dry clutch version which he hopes they’ll introduce when the current production run is over. But then it wouldn’t be a Boy Racer anymore. |j§]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue