ROAD ATLANTA

JOHN WAASER

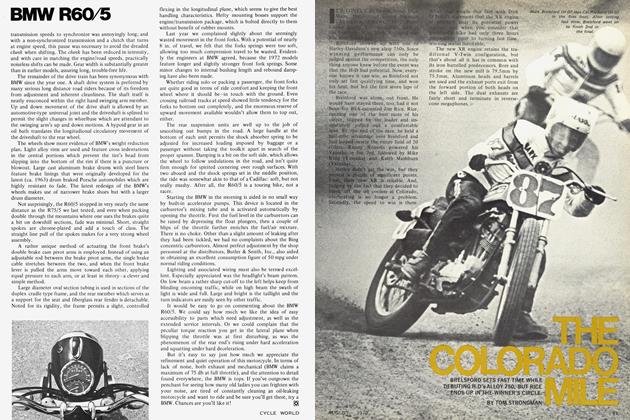

THE GREATEST ROADS in the world have to be the back roads of the Southeastern United States. Moonshine running roads. Roads like Route 25, which runs from southern Tennessee into North Carolina; up hill and down; fast, sweeping, blind turns followed by quick switchbacks; right turns, left turns; and all the while a steep cliff rising up one side, and a plummeting 50-ft. drop should you hang a wheel over the other side. Where merely driving into town for the weekly groceries is a sport, and every village has its own quarter-mile paved oval sitting in what may first appear to be a vacant field.

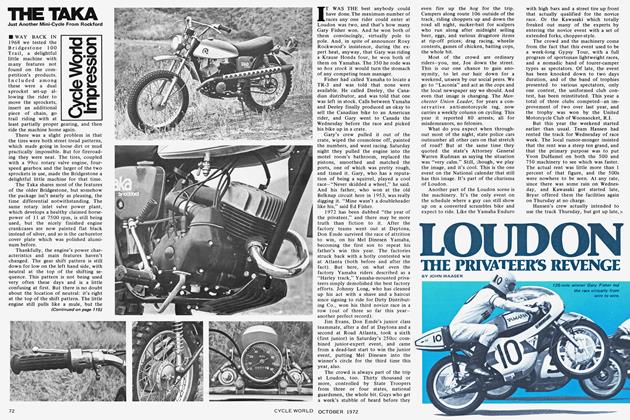

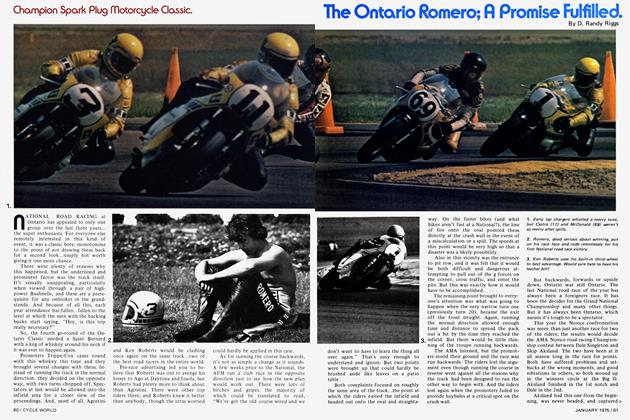

A race track nestled in these rolling hills has to be something special, and Road Atlanta is. For starters, it has some of the best facilities to be found anywhere. Clean, modern, concrete structures house the press tower, the concession stands, rest rooms and showers. The track surface itself was properly done, and is smooth even after two seasons of use. Road Atlanta is operated in a thoroughly professional manner, too. The only complaint anybody had was about the pit location. The pits were placed so that the spectators could see all the action, and the crews could get to them easily. The only flaw is that the pit entrance and exit are on one of the fastest portions of the course. In fact, the pit exit puts a rider right into the fast line for turn one. Other than that, everyone was unanimous in their praise of both track and management.

It seems certain that he who laid out this course got his early driving experience running ’shine through those southern Appalachian hills. A slow track, by current standards, where the bikes hit just a touch above 140 mph, some 30 mph down on the super bowls. And every inch a driver’s course, with a series of downhill esses leading into an uphill ess. The scariest is a high-speed right. For the cars it’s not off-camber, and for the fastest bikes it’s not either, as they run wide to set up for the following left. But the slower bikes come through there on a tight line; and from a distance, as you watch, almost peering over the rider’s shoulder, you expect to see his front wheel wash out and the bike tumble into oblivion.

With this kind of course you might expect that tires would play a major part in the racing-and you’d be right. Goodyear wasn’t offering any of their treadless Bonneville-cum-Daytona numbers here. They had new compounds, and a wider front rib for the riders to play with-a total of nine different tires in all. But while many riders agreed that Goodyear might have better compounds than Dunlop, most of the fastest riders were on Dunlops, whose triangular shape puts more rubber on the road when things start happening.

Most riders were going with the same tires they had at Daytona, but the Suzuki team was playing with a new wider triangle. And Dunlop had a factory engineer over from England to gauge the performance of the rubber, and report back to the mother country. Goodyear people thought Suzuki had gone about it backwards. They should choose their tires first, then design the chassis to go around them, said Goodyear, indicating that this is how Indy cars are built.

Cal Rayborn commented to a Goodyear official about the way they do things in England. It seems that in the past Cal had used two rims, with one tire size each, for all his racing. In England, they had handed him different size rims at every track, and even switched tire sizes on the rim, optimizing the combination for each course. And he admitted he could feel the difference. It was an eye-opener for America’s best road racer, and he gained knowledge that should make him nearly unbeatable when Harley Davidson gets its new machinery cooking.

When asked on Friday who was going to win, racer Steve McLaughlin replied, “Put money on Calvin.” The theory was that Cal was so “up” for the win following his impressive performance at the English match races that nobody could stop him. But Cal’s Hot Dog, the year-old Harley that had carried him to three major English victories, could. Cal likened his bike to riding a hand grenade with a 10-sec. fuse. It forged its way to the pits early in the race, and after a brief but valiant effort, returned there to sit with its magneto cover removed, and two mechanics discussing some dry, but darker than normal, plug readings.

Harley-Davidson was but one of three major entrants to have problems of another sort. When I got there on Friday, the Suzukis, the Beezumphs and Cal’s Harley had all failed to arrive at the track. Suzuki had even rented the track on Thursday for some tire testing, and when the machines failed to make it, they threw the track open for general practice. But by Saturday, all three teams had solved that little hurdle. Cal spent Friday standing around, watching, chatting, making worried phone calls to Daytona (where sat his Harley-all in pieces). He loaned his boots to Kenny Roberts, who had forgotten to bring any.

The schedule here is different from Daytona, too. Not that anybody got much sleep at Daytona, either, but there at least you had a whole week to sort things out. Here you practiced on Friday, and tore the machine down for inspection Friday night. If you blew, or had ignition problems, or whatever, Friday night was busy. Saturday was the 250 race-in the morning, at that-and you had to be ready for it-novices, juniors, and experts alike. Saturday was tense. Those whose bikes didn’t make it on Friday got a few limited practice laps early, then they held the novice and lightweight combined junior-expert events in the morning in order to allow the motocross to fill the afternoon. Pat Evans went off down the track on his own just prior to the novice race. Charlie Watson didn’t like that a bit, and started to give him one hell of a chewing out right there on the line in front of God and everybody. Bill Boyce didn’t like that all too much, and told Charlie to either let the kid ride, or kick him out. The Yamaha team member and fastest qualifier was allowed to ride, but Charlie’s patience had worn thin. As the 1-min. flag went up, Daytona novice winner Johnny Long’s bike was not running on the line. So Johnny pushed off in the direction of travel, and got it started, then blasted back for the line. Old Charlie had had enough. If looks could kill, Johnny would have been an instant stiff. Charlie angrily pulled him off to the side, and let him start at the back of his wave. At the rider’s meeting on Sunday riders were told that if they were pulled off the line at the 1-min. mark, they would have to start after the last wave. Evans didn’t think Long should have been allowed to start with the first wave. But Pat didn’t make a formal protest, and Long’s first wave start was allowed to stand. Off the line in front it was Evans and Mike Devlin. Mike looked faster on the clutch, but into the first turn Pat was ahead of Mike. Mike was wearing a new kind of road racing boot, with an unusually thick sole. But he’s so tall he can’t tuck in properly, and the sole wore out quickly enough anyway. (Kenny Roberts picked up a pair of the same kind of boots from Gary Nixon Enterprises, after he had to return Rayborn’s proper style racing boots.) Several laps after the start, Jessie Byars went down hard in the last turn, really tearing up the hay bales with his bod as he skittered across the course. Around the corner came Peter Baer, who hit Jessie’s spinning wheels and flipped, though less spectacularly than Jessie had. But Peter’s bike caught on fire, right on the outside edge of the track, dangerously close to where the fastest riders wanted to be. For a split second, track officials scurried around looking for the extinguisher, which was by the starter’s box, sort of hidden. They found it quickly, however, and ran to the scene, put the fire out, and carted the motorcycle off the track. Very professional, these SCCA boys. The ambulance crew’s handling of Jessie, however, was less professional. Luckily he was not seriously injured. >

ROAD ATLANTA

Meanwhile, up front, Johnny Long had moved quickly through the pack, up to second place. Eventually he got by Pat Evans, and built up a good lead, on an obviously quicker motor. Devlin was farther back in third. Whether Long could have won starting from the rear of the second wave is highly debatable. But this was the sort of officiating which seemed to be going on all weekend. First Evans was allowed on the grid when he could have been bounced, then Long was knocked off under similar, albeit more tense, circumstances, and allowed to start with his own wave when he should have started after the second wave.

The most exciting race of the weekend, really, was the combined juniorexpert lightweight affair. Mike Lane (who’s getting sick of being called Johnny by the AMA; he always puts Mike in parentheses on the entry blank, and they always ignore it) got the early lead. Mike could hardly have been called smooth out there. In fact, one wellknown rider had earlier said of Mike, “I hope he’s far out in front of me when he goes down.” Mike later explained that he’d changed his gearing, and could only pull fifth while drafting someone, so he had to give it his all in the corners. Nevertheless, through the esses he looked bloody awful.

Ron Pierce was right on his tail all the way, with Kel Carruthers maintaining a safe distance behind the two of them. Ron was riding beautifully, flicking his bike through the turns with the precision of a ballet dancer, riding perhaps his best race since he was disqualified for winning the 750cc junior race at Loudon on a 250. For a while I wondered if it was only the contrast with Lane’s riding which made Ron look so good, but Kel Carruthers also had noticed. ‘T can’t believe it’s the Ron Pierce I know,” said Kel. Toward the end of the race Ron got by Mike when Lane blew a shift, and then Kel quickly overhauled the two of them. On the last lap you could have covered the three of them with a bikini, but at the finish line it was Kel first, Ron second, and Mike third. Mrs. Carruthers was fond of noting that this wasn’t the first time this week that Kel had beaten Ron Pierce. It seems that on the way to the track they had passed a Winnebago motor home which then picked up speed and repassed them, the driver flashing a peace sign as he went by. “Who’s that?” Kel asked his wife. “It must be Ron Pierce,” she replied. With that, Kel “gassed it and left them.”

The ambulance crew came in for some more static in this event, too, as apparently Kenny Roberts felt they had taken up a little too much room on the track and slowed him down at one point. So while we’re talking about them, we might as well add that they seemed to take an unduly long time getting George Roche into the ambulance after he broke a swinging arm bolt in the expert event. Then they took about a full lap after he was in there before they got the ambulance moving. As I watched the affair, I thought, “Either he’s not hurt, or he’s dying, otherwise they’d rush it a bit.” And since he did not appear to be moving.... Expert winner Jody Nicholas had unkind words for them, also. Roche was quite all right, by the way, though his good friend Hurley Wilvert was also unnerved by the length of time he spent on the ground, and dropped out of the race to check on him.

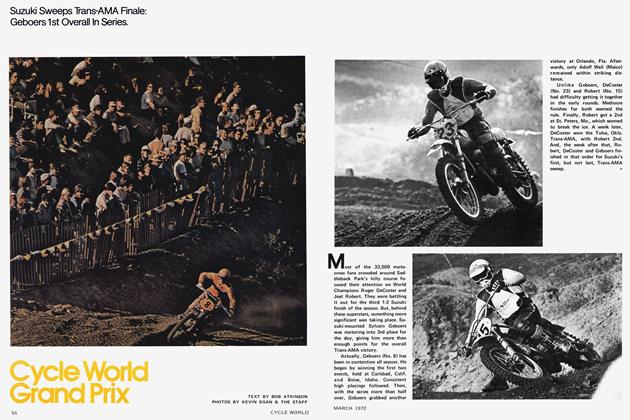

The motocross was held Saturday afternoon on what was really a pretty decent course. The rolling foothills of the Appalachian mountain chain provided some excellent natural terrain to play with, and the Husqvarna crew did a terrific job of laying out the course. Crowd control was good, with legitimate photographers allowed anywhere their hearts desired, unlike some other recent events. Spectators were allowed very close to the course, but not on it. Goodyear was giving away its new motocross tires to anybody who would use one, and wound up with some very impressive riders on the American tire, including (they say) Open class winner Barry Higgens. Barry was calling himself a Georgia native today, though he’s originally from New York, and New Englanders are fond of claiming him as their own. Spectators missed seeing Jimmy Weinert, who has the worst luck of any motocrosser going. He’d had a spectacular accident the week before, injuring at least one spectator even worse than himself from all reports.

One of the most interesting aspects of the motocross was the participation of a large contingent of New Englanders. New England scrambles and motocross races have been run without the benefit of AMA sanction for several years. Only two New Englanders did poorly here, however. One is a class champion back home (he couldn’t get motoring, and finally took a bad spill which had him on crutches the next day) and the other was Glenn Vincent, acknowledged to be among the best in the land, who broke a leg very badly in the third moto. He had accumulated enough points in the first two to raise him above the bottom of the standings, however. Reports indicate he may be out of action for some time. A standout performer was Dave Robinson, a firstyear expert in New England who bought a couple of new Huskies and went to Florida for the winter with instructions from his father to either get good or give up that silly sport. Always high in each moto, he led the last one for a long while before finally dropping off the pace. He finished 5th overall—and of the four riders ahead of him, three were Barry Higgens, Gary Semics, and Wyman Priddy. ’Nuff said.

Years ago, when Higgens was just starting out in the sport of scrambles, he rode out of Sal DeFeo’s Ghost Motorcycle Sales. Part of the job description included taking under his wing Sal’s son, a skinny little kid who got in everybody’s way, and wasn’t above falsifying his age to sign up at an important meet. Soon Sonny started to grow, and as he did so he became a very fast motorcycle rider, even leading Higgens on occasion. But he fell a lot, and when he got over that he just didn’t have the stamina to be around at the finish. Then he began to fill out, and became a figure to be reckoned with. C-Z sent him to Europe for a few events one summer, and he came back better than ever, but rarely did anything in AMA events, largely because he couldn’t get along with the officiating. Well, if you expected Gunnar Lindstrom to win the 250cc class on the course he helped to design, you reckoned without Sonny DeFeo. His old riding buddy Barry Higgens won the open class, and Sonny made it a day for his father as he beat the hot-shoes in the 250 class.

Don Vesco was busy changing tanks so that he would not have to use any elaborate fueling devices the next day. This last practice was universal, by the way, among the Yamaha riders, even though the quick-fill units could fill the entire tank in less time than you could add a gallon without them. Perhaps they felt that quicker lap times with only a gallon added would offset the extra speed of the quick-fill pit stop.

In fact, following Sunday’s race the Team Hansen mechanics were discussing the effects of a gas stop with Gary Nixon. As you use gas, the weight and center of gravity change subtly with each lap. But when you go back out after a pit stop, you’ve got another 45 lb. of gas, high up on the bike. You’ve changed acceleration, braking, handling, vibration characteristics, fuel pressure to the carbs, and a host of other variables, all at once, and it takes you a couple of laps to adjust.

If the lightweight combined was the most exciting race of the weekend, the heavyweight junior was the most interesting. Rain had threatened early in the day, and in fact cut one expert heat short, so that qualifying positions were taken from the third lap instead of the fifth, of both expert heats. But after a brief, hard shower, the sun came out and dried everything off quickly. Good thing, too, as that red Georgia clay is slippery when wet!

Pole position holder Howard Lynggard had exercized his option to specify the outside position in the front row. The first turn is way down at the end of the long front straight, and you want to be on the outside edge as you come into it. Not only does the man on the outside have the “right” line, he can shut off anyone on the inside of him quite handily, should it come to that, and the pole position holder doesn’t want those tricks played on HIM.

As the 1-min. board turned horizontal, Howard discovered his clutch had frozen, and he couldn’t get the bike in gear. With 10 seconds until the flag, he pulled off the track and waited for the whole field to start before they finally decided to shut off his motor, and push him off with no clutch. As the mechanics pushed, Howard banged the machine in gear; the bike caught on one, and was running clean by the second lap. His poor luck should have given sixth qualifier Evans an unbelievable chance at a hole shot. But Jim didn’t feed enough revs or something; he couldn’t let the clutch out fast enough, and got a mediocre start.

ROAD ATLANTA

Down the straight shot Jerry Greene, in a lead he was never to relinquish. Meanwhile, three riders were moving through the pack. Jimmy Chen was doing beautifully on his Honda. We could have seen a beautiful race between Chen and Evans, except that the Honda started to sour, it cleared up for a few laps, then went bad again. It seems that Jimmy had had shifting problems earlier in the week, which had since been cured. But they left the bike with four (count ’em) bent exhaust valves. A monumental ride carried him to 3rd, nevertheless.

Jimmy had another problem. He had started the week with stock Honda shocks, and they just weren’t up to it. Remember we said the surface of this course is smooth. But the natural changes in elevation along the way demand the most from your suspension. Koni rep Walt VonSchoenfeld feels very strongly that the AMA should approve rear shock absorbers in the same manner as they approve frames and front forks, and mentioned a new externally adjustable for both bump and rebound Koni, said to be available by Loudon.

Chen borrowed a set of Konis from a local rider, and wanted to take them off in Victory Lane, to the horror of AMA officials, who finally let him return them to their rightful owner during the post-race teardown. The Koni people also elected to give a set of shocks to Don Emde in the trackside pits during the junior race. As Don came down to accept the shocks, he found Mel Dinesen giving frantic hand signals to Jim Evans-they had no pit board for him. Emde took his own pit board, turned it upside down, and wrote information to flash to his young teammate, who was cutting through the pack with laps less than a second off the leading pace. Jim got into 2nd soon enough, but couldn’t whittle Greene’s lead.

What of Lynggard, the factory Yamaha rider? He was well into the pack by the fourth lap, and clear of the second wave by the fifth lap in one of the finest displays of riding this class will see for a long time. And his clutch didn’t free until about the twelfth lap; these early laps were run without the benefit of that useless appendage. Cutting laps as fast as Jerry Greene’s, Howard finished the race in 4th, and would doubtless have had 3rd in just a couple more laps. Greene, who won the race by over a 20-sec. margin, was hustled into Victory Lane. When his tuner, Irv Kanemoto, attempted to join him there, the officials wouldn’t let him in until all the bikes had arrived. Jerry was incensed. He had little patience with the photographers, finally bursting out with “Take a picture of my tuner, you guys.” Hours later, at a local restaurant, he still felt the same way; much of the credit for the win should go to Irv.

Jody Nicholas grew up in these same hills, and rode these same back roads, years ago. A road racing specialist, he has been a member of the Suzuki factory team. His strategy is to get near the front, and wait for the squirrels to break. All too often it has been Jody who has broken. In this year’s English match series, he finished second American to Cal Rayborn. He was ready for another big win after seven years of obscurity. Art Baumann had the pole for the big one. Like Howard Lynggard, Art had wanted the outside slot. But unlike Howard, he waited until the last minute to ask for it, and Charlie Watson turned him down cold. Charlie’s stand, of course, was not unreasonable. What was unreasonable was that while the riders knew of their right to specify the position they wanted, nobody had told them that they must do so before they lined up. Art figured it cost him some lap money.

The three Green Kawasakis squirted into the lead on the first lap. Paul Smart stayed real close to Duhamel for a time, but Gary Nixon started dropping back early. Well into the shuffle was Cliff Carr, on a private (Arlington Motor Sports) Kawasaki. Roger Reiman (remember last year’s dark horse 4th place finisher at Daytona?) on a Honda, was in the fray, too, but started smoking, letting Ron Pierce and Kel Carruthers through for the first Yamahas.

Kenny Roberts had somewhat detuned himself in some early Sunday practice when he forgot that his 350 had a six-speed gearbox. It seems that minimum production rules aren’t enough for the AMA, who have decreed that six-speed boxes are not production items. Those “obsolete” single-cylinder Maicos which won the 125cc class at Daytona, for instance, aren’t production (not any more than a TD-2 Yamaha, they’re not—or a KR Harley...). And such bikes as the Suzuki Hustler and Bridgestone GTR, well, they never existed either; at least not 200 of them in race trim. The LIM isn’t so narrowminded, and since AMA National Championship races are run under LIM rules, six-speed gearboxes are legal in the big event, but not in the others.

Having ridden his five-speed 250 all week, Kenny downshifted the bigger bike twice, got his tach reading about right for the corner, and too late found out he was a gear higher than he wanted to be, and was running way too fast. “I need a blank check...to fix my bike,” he told team manager Art Barda. Actually the bike wasn’t hurt all that badly, but there was no way they could get it going for the race. Since it all happened before qualifying, Kenny borrowed Kel Carruther’s spare machine—and proceeded to pass his benefactor in the heat. A guy could lose his ride that way.... During the race, Kenny concentrated on remembering how many speeds the bike had, and stayed back away, finally crossing the line in 9th, adding fifty-odd points to his National Championship points lead. Mike Lane and Cal Rayborn pitted early, to be joined by the likes of Ron Pierce and Art Baumann. When asked what the trouble was, Art replied “Crankshaft, I’m pretty sure,” but later changed his mind and said ignition. Strange are the ways of PR....

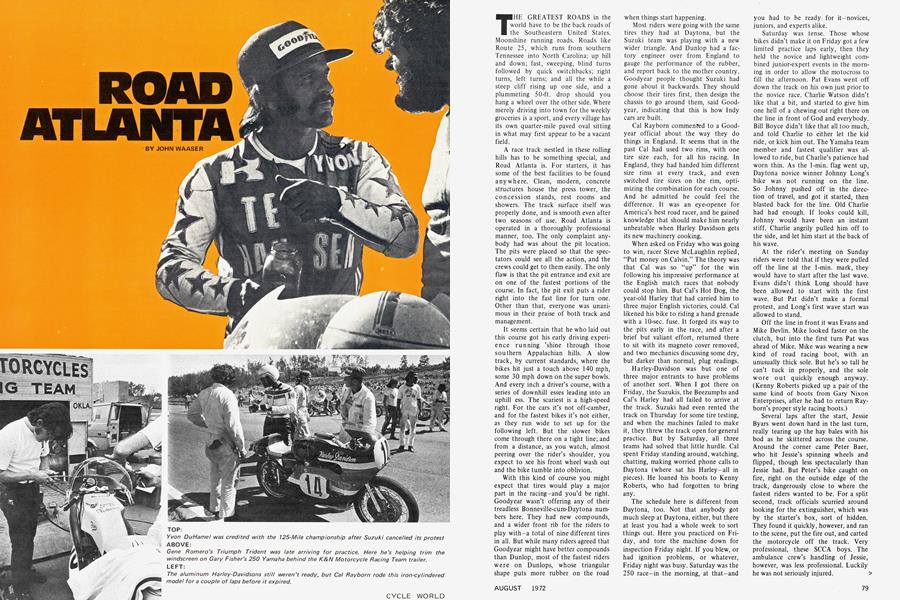

Mann and Romero had their threes running reliably, at least, after some early problems with transmission, oil leaks, and push rods that wouldn’t push. But when the opposition is going down the back straight at better than a hundred and forty, and when Kenny Roberts can pull you out of the uphill esses on a 350, reliability isn’t exactly the name of the game anymore. Gene seemed to have a bit more steam than Dick, and was able to pull away from the champ after a while. The fourstrokes also were able to go without a pit stop, so while there was a great dice between Romero, Mann, Roberts and Carruthers for awhile, Kenny and Kel both pitted for gas on the same lap (unplanned) about the time Gene found a quicker way, and the dice broke up. Kenny took way too long in the pits, and lost touch with Kel.

But for Jody, it was an uneventful trip from the fifth lap or so when he hit a hay bale after having been cut off, up through the finish line. The wind was a bit much, as the back straight includes a moderate rise, just beyond the crest of which is a slight turn. As you crest the rise, your front forks extend and the wind would like to send you flying. But it doesn’t, unless you forget it’s there.

The AMA officials were finally putting some teeth into the “production” aspect of the rules this week. They carted along a truckload of “stock” crankcase, cylinder and head castings to compare with those on the racing bikes. Keeping the factories honest can only help the sport in this, the “yeat of the privateer.” During pre-race tech inspection, Bill Boyce had informed Suzuki that their head castings were nonstandard. Suzuki appealed and was allowed to run the race under protest.

Rumors all week said that it was Bob Hansen who had protested the Suzukis initially, but Bob and other AMA officials deny that. In fact, the Kawasakis were looked at as closely as the Suzukis in the post race teardown. (One privateer who bought six Kawasaki cylinder heads from Team Hansen noted that they were so stock he could only salvage three of them. Spark plug holes weren’t even drilled parallel to the bore in four of them, he said.) But the AMA’s action, and the timing of it do lead to certain inevitable questions. Why not at Daytona? Why after the trip to England? Why just at a time when Kawasaki and Harley-Davidson have been taking such obvious pains to be “legal?” Bill Boyce certainly wasn’t answering questions. In fact, he refused to allow reporters and photographers near the teardown site, and got decidedly upset if anyone flashed a camera in that direction from a distance.

Bob Hansen said he was pleased that the AMA was finally ensuring the legality of race machinery themselves, instead of waiting for a competitor to protest a suspected machine. But, he noted, there was 48 hours from the discovery of the “illegal” heads to the race; a protest committee could have been formed to decide upon the matter before the race. By allowing Suzuki to run under protest, there was a possibility that Suzuki could win and advertise the win for a month before finally being disqualified. Bob also mentioned an increased risk—scoffed at by Suzuki rider Nicholas—of having three more competitors on the track: three more chances for an accident; forcing the competition to ride all the harder, and for what—a subsequent disqualification. Bob was displeased at that situation. And he was more displeased after the race, when Suzuki had won.

The AMA officials tore down the winning bikes, and declared the Suzukis of Grant and Nicholas illegal. To show you how picayune the thing is, the rules allow a competitor to heli-arc and remachine the combustion chamber. So the only things Suzuki could have changed by going to a non-standard casting would be the spark plug location or the water jacketing. From all reports the jacketing works fine on the stock head. And the spark plug location probably falls under the heading of something that can be heli-arced and remachined. But the AMA was adamant; the bikes were illegal.

Suzuki protested again. Ed Youngblood told me at the track that a protest committee would be formed to resolve the matter on Tuesday, some 48 hours later. Meanwhile, the track had released “official” results, to the total consternation of the AMA. A call to Youngblood at the AMA offices was met with a curt, “He isn’t the one to help you.” With that the operator put me on with another staffer, who revealed that the protest committee meeting had been put off until May 1st, thus bringing to full fruition the worst of Hansen’s fears.

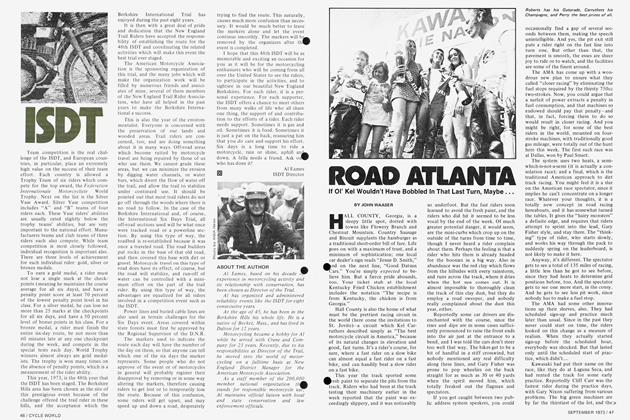

Jody Nicholas simply outrode everybody to come home 1st. That much is certain, and as he said, “It’s been a long wait.” Duhamel knew he was in 2nd, but didn’t know who was in 1st. In Victory Lane he turned to Jody and said in his best French Canadian accent, “I didn’t know who was in front, you son of a gun—if it was you, OK....” It was a popular victory.

Waiting in the eaves were not only the manufacturers of the contending machines (and Kawasaki’s huge contingency fund), but the accessory manufacturers. Jody was on Dunlops, Yvon was on Goodyears. The Suzuki had Japanese shocks, the Kawasaki had Konis. Bob Lenk, a lifetime friend of Jody’s, was piqued to learn that the Suzuki team had run out of Cycle News Stickies. Nicholas didn’t have one, Duhamel did. At a time when we have over $25,000 in contingency prizes at one race, the manufacturers have a right to expect clear-cut victories for advertising purposes. Without them, the contingency money will go elsewhere. Insisting on stock parts is a good thing. But saying, “We insist on stock parts, as long as you don’t protest our insistence,” is hardly worth the effort. The AMA had their chance to do something great for the sport, and they blew it. Bad.

Thus it was all too anticlimatic when only a few weeks later Suzuki called up the AMA and cancelled its appeal. Exeunt Nicholas and Grant from the result sheet.

Officially, they never existed. But the public knows better. [O]

RESULTS