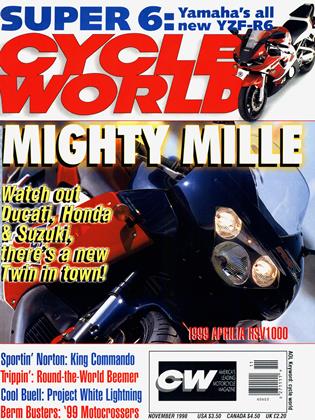

Italian Style

Shape, color, noise and speed

EVEN NON-MOTORCYCLISTS ARE DRAWN TO TUE powerful shape and color of Italian machines such as the Ducati 916, the MV Agusta F4 and now Aprilia's RSV Mille. Their shapes are organic rather than geometric or merely mechanical, and they have evident purpose.

The power of Italian design to command our attention does not arise out of nothing. The machines of other nations share the same basic features-wheels, engines and chassis-but few achieve the visual impact of machines from Italy. In most industries, styling is something super ficial, added after the engineering is done, and may be bought from design houses. In Italy, the engineers are themselves stylists. Certainly there have been ugly Italian motorcycles, but the beautiful ones more than make up for them.

KEVIN CAMERON

The best of Italian design seeks a visually successful way to integrate and arrange the elements of a useful object. It is based on reality, and not on denying or concealing it. The goal is to create a thing that is beautiful in its use and not just in the abstract.

Other things besides motorcycles are beautiful in Italy. The ordinary details of life are thoughtfully and gracefully designed. A taste for beautiful things is genetic in this country, as is the honor accorded to those who create them. The Italians are surrounded by classical Roman buildings and can drive on the 2000-year-old Via Appia. Everywhere are the art and architecture of the Renaissance. A tradition of design stretches back forever, extending vigorously through the turbulent and confusing 20th century to the present day.

In 1900, human optimism was limitless. The Age of Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution had explained the motions of the planets, driven railway tunnels through the Alps and erected iron bridges across w ide rivers.

Nothing was impossible-especially when radio, the automobile and the airplane promised speed to shrink distance to a mere point. Progressive artists weren’t satisfied with elaborations of past styles; they wanted to express all this. The arts, they asserted, had slept since the Renaissance, left behind by humanity’s new powers. It was time for revolution.

In 1909, the flamboyant Italian poet Marinetti issued the manifesto of Futurism: “We affirm...a new beauty; the beauty of speed,” he wrote.

Stating that “museums are cemeteries,” he announced that “objects in motion multiply and distort themselves.” Movement itself became the subject. The Futurists urged that cities be blown up and given a fresh start.

Their movement didn’t last, but it was a symptom of something more solid—a long-running Italian insistence that technology and the changes it forces find human, organic expression. The alternative was a life split in two: on one side, technology marching ahead, changing our lives; on the other, the arts, which express w hat we feel about life. This separation was possible and even fashionable in other nations. Not in Italy, where races were long held over public roads. These were great public spectacles, as thousands of villagers lined the roadsides for hours to see terrifying racing cars thunder by, flaming meteors from the future. In Italy the arts are a response to being alive now, not a fixed expression, a fine art prescribed by an academy.

Intrinsic pleasure-beauty-is possible in all of man’s works, and the Italians insist on it. Beginning with that unwilling and unlikely material, concrete,

Pier Luigi Nervi made organic shapes that looked light enough to fly. He said of himself, “I am just an engineer,” but his work has an appealing “rightness”—it is certainly beautiful. Such engineer-designers believe that life and the practical, the organic and technology, can’t be separated. The late John Britten would agree. Trained in the arts but working as an engineer, he regarded organic forms as the gift of a billion years of evolutionary R&D.

That alone makes it foolish to put the arts and technology in separate boxes. There is, he said, only one aesthetic.

Modern life too often imposes the reverse. The artist, defending the intuitive, insists on the unworkable, while the engineer, trained to distrust beauty, insists on the ugly. We are delighted when they combine as they do in Nervi’s work and in the Ducati 916.

It’s impossible to think of Italy without also thinking of the Renaissance, of the discovery of perspective, of the art and engineering of Leonardo da Vinci. Why Italy? Sticking out into the Mediterranean Sea, Italy was a natural focus of trade and exchange as Europe was lifted out of the Middle Ages by the growth of trade and towns. Every city-state, every artisan's shop, developed its own distinguishing styles, which became a useful language of recognition. Novelty therefore became more valuable than convention. Practical workmen were therefore free to observe nature as it was, and use and depict it as they saw fit. This was the basis of a new art.

Italian industrial design celebrates function. Nervi’s structures are beautiful because they reveal the forces that sustain them. Aircraft become beautiful when they assume the shape of the airflow around them, in this view, beauty is not something added-it comes w ith good design. The reduction of an object to its functional essentials reveals its interior principle. Wings blended into fuselages, engine nacelles and propeller spinners.

SI ATA created a streamlined auto whose fenders blended into its body like haunches and shoulders, and this theme continued w ith postwar autos like Piero Dusio’s Cisitalia and the Maserati A6GCS. Bertone created for Citroen the fish-like DS auto. All had “envelope coach work” that gave the automobile a single shape. Italian designers love to discover new materials. When carbonfiber and carbon-kevlar fabrics became structural materials in racing cars and motorcycles, Italian designers embraced them and featured them in their designs-unpainted and unadorned. A generation earlier. Carcano had done the same w ith unpainted, un-gel-coated fiberglass on his Guzzi racebikes.

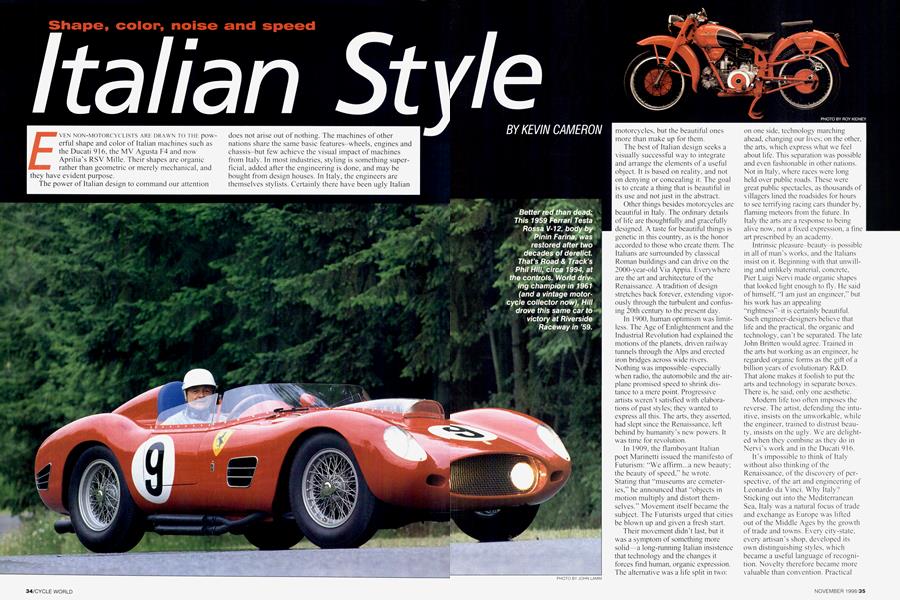

No name has more power in automotive design than Ferrari, w hose Grand Prix racecars quickly evolved in the 1950s from ordinary functionality to the great animal beauty of the last Supersqualos of late 1956. The motorcycle, long lacking a “body,” has been harder to integrate. Separate parts w ere joined only by the lines of exhaust pipes or frame members, or by shape congruency. Fuel tanks more easily took organic shape-think of the sensuous shape of the cool blue-and-silver Ducati Diana 250 tank, or the round watermelon ripeness of years of Moto Guzzi tanks.

Color is a message in itself. Red is the color of blood and life-no other color carries this meaning. There are green Ferraris and yellow Ducatis, but the gene for red in Italian vehicles is dominant. The Mediterranean love affair with color began before Grecian Homer described the “wine-dark sea.” Color is a necessity in a land of light and contrast. Sightless and stony today, the statuary of ancient Greece was originally painted in vivid color. Traditionalists are offended by the latest restoration of Michelangelo's Sistine paintings-they are too bright and cheerful to be properly “classical”-that is. dreary. Find the same color brightness in 1500 B.C. Minoan frescoes, find the same brick-reds and sunyellows in Pompeian paintings. The sun and the colors it powers are strong here, much brighter than the little brass lamps that illuminate age-darkened classical paintings in museums. Even the food is brilliantly colored-peppers, tomatoes, eggplant. Color isn't a choice, it’s a necessity.

In the late 1980s and the ’90s, practical men at Ducati’s race department faced and solved technical problems. They mastered the huge noise of the 851 engine with a multiple-path exhaust system and two large silencers. Those silencers, which otherwise resemble RFD mailboxes or comic wheelbarrow handles, migrated to the only protected and visually right place-under the rider’s seat. Racing, wdth its constant rebuilding and servicing, forces an evolution toward sense and convenience. Components find their best places through a forced, constant reconsideration of everything. This distinguishes the 851/916 from the usual objects of industrial design, like toasters or computer monitors, which are engineered in one place, then styled in another. Like the Ferraris and Maseratis of an earlier time, the motorcycle has been shaped both by intention and by use. It actually has the qualities its form so strongly suggests. Its neat compactness looks right because it has proven to be so.

This is everything for w'hich Italian design has worked.

The shaping of the seats, fuel tanks and fairings on the Ducati 916 and MV Agusta F4. for example, are not arbitrary; they make a place shaped to receive a human rider. A step along the way to this was the fully enclosed Ducati Paso, which is to the 916 as the Ferrari 166 was to the Testa Rossa. The sensuous shapes of the great front-engined Ferraris of the late 1950s may never be equaled, now that the automobile has become a social nuisance rather than a romantic technological adventure.

Italian racing motorcycle engines of the 1950s and '60s are beautiful because their shape suggests what is inside. Two prominent camboxes defined the head; the wheelcase for the spur gears of the camdrive extended downward from it. Generous finning covered head and cylinders. Jutting downdraft carburetors occupied the intake side, and sweeping exhausts curved down, back and up to terminate in one, tw o or four (often finely curved) black megaphones. On one side or the other was the dry clutch, spinning visibly as the engine ran. Underneath lay a long, deep-finned sump-designed to act as an oil cooler. In action this was a stirring spectacle, as impressive to motorcyclists as steam locomotives once were to little boys. One of the most beautiful of racing engines was the 250 Morini. It didn’t need styling-its elegantly revealed function defined style as does the shape of a racehorse.

There are other opinions. In the postwar era, there was a strange, tacit international agreement among certain designers (at BSA, NSU, Motobi and Rumi, to name a few) that engine cases, cylinders and heads should resemble eggs or other arbitrary shapes. This was functionally okay as long as the performance of the engine was so low that it didn’t matter where or how deep the cooling fins were. The horizontal-cylinder Motobi is a leading example. The needs of cooling contradict the egg look; the greatest fin depth is needed on the head and at the top of the cylinder. Wherever power and lightness were important, function determined how engines looked. This created an aesthetic of power that persists to this day. Crankcase and camdrive castings are the minimum required for oil-tightness, so they are naturally shaped like their contents-gears and crankshaft. The sump grew deeper and longer to hold more oil, and developed fins to cool it.

The postwar European motorcycle boom ended in 1957-58, leaving little money for racing or new models. The industry slept until a new prosperity awakened it in the 1970s. In this quiet period, MV Agusta continued to race, defining a whole-bike look soon reproduced in the 1960s racers from Japan. This featured a far-rearward seating position, behind a long, slim “breadloaf’ fuel tank. The slab-sided fairing was less for aerodynamics than to carry the numbers. Engines were mounted against the rear tire, making swingarms short. This look was dictated by the narrow, hard tires of the '60s, making it necessary to put the weight of the rider and engine rearward to prevent off-corner wheelspin. This remained the sporting look until wider and softer tires changed the shape of racing motorcycles at the end of the 1970s.

Increasing tire grip forced weight to move forward, to keep enough load on the front tire for steering. Fuel tanks have become shorter longitudinally, taller and wider, to allow the rider to sit forward. Finding room for fuel has forced the designer to mold the tank closely to the rider’s anatomy. Engines have likewise moved as far forward as possible, making swingarms longer and eliminating the prominent I950s/’60s gap between front wheel and engine.

In the recent period, tiny Bimota has been a major stylistic influence. They have tried to do for motorcycles what was done for cars in the 1940s and ’50s-to join many functional elements into a single coherent shape. Bimota fixed upon the inherent attractiveness of recent-era factory-racer construction, in which many parts are CNC-milled from aluminum or magnesium billet. Bimota integrated this into truly beautiful machines. Visually prominent functional items like brake calipers, fork legs and disc carriers were left strictly alone; like engines, they already succeed because of their obvious visible fitness. The result updates the I950s/’60s race look to the level of current technique, industrial art at its best.

The idea that engines should be styled never dies-Ducati, for example, allowed the hard-edged influence of Giugiaro to affect its later Twins. As with the human body, the basic muscular, functional form is obscured if styling is something added (like fat), and there is an attendant gain in weight and loss of performance. Just when I think the motorcycle is defining itself nicely, arbitrary styling reappears. Philippe Starck’s rounded-off, toy-like design for the Aprilia 6.5 is an example. The egg-man lives.

The idea of a style based on function is appealing, but the underlying look of the sports motorcycle dates to a political act in 1958. Before that year, full streamlining was developing rapidly on racing machines (some of which were outstandingly ugly, by the way). The FIM put an end to it, mandating a partially streamlined vehicle whose rider and wheels must be visible from both sides, with no streamlining forward of a vertical plane through the front axle (today, 100mm ahead of it). The linkage between racing and sales means production sportbikes today dare not stray far from this 40year-old theme-anything else would “look funny.” The drag coefficients of today’s swoopy-looking motorcycles are therefore no better than those of trucks. Can this change? Can there be an entirely new, functionally superior motorcycle? Is there a designer who can make something completely different, that doesn’t upset us, that looks right?

Maybe in a small studio, somewhere in the north of Italy... □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontUjm Redux?

November 1998 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsBuying A Shadow

November 1998 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCOut of Bounds

November 1998 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1998 -

Roundup

RoundupHarley To Buy Ktm?

November 1998 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupCagiva/ducati Divorce

November 1998 By Brian Catterson