Setting the Standards

RACE WATCH

600 SUPERSPORT: World-class racing, world-class bikes

KEVIN CAMERON

HERE’S THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO Honda's Assistant VP of Operations, Ray Blank: “The 600s are the new standard. People are making a mistake if they think ‘standard’ means high bars, twin shocks and no streamlining. What standard really means is, the most versatile motorcycle, purchased in the largest numbers, for the widest variety of reasons. And that’s what 600s are.”

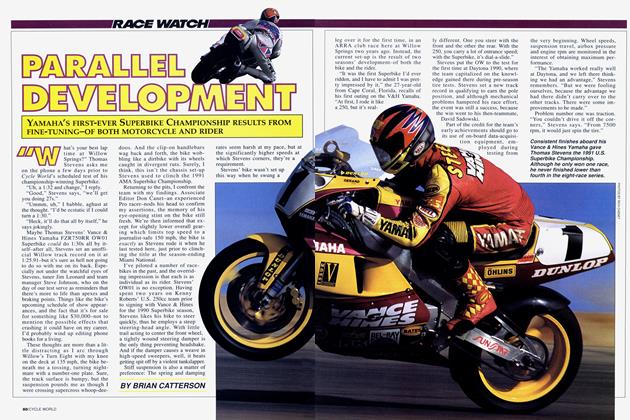

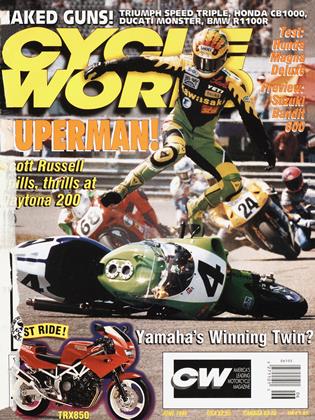

Blank was replying to questions most people were asking at Daytona: Why are the factory teams putting as much effort into winning 600 Supersport as they are in Superbike? Why were top World Superbike riders Doug Polen and Scott Russell risked in this production class?

The answer is that 600s are what the makers sell, and racing helps to build the essential mythology that sells them. Most Daytona pundits feel that the real reason Honda hired Miguel Duhamel back from Harley-Davidson (at a rumored prince’s ransom) was to do what he does best: win 600 races. And win he did, despite stunningly fast practice times by Scott Russell, who would not finish the event.

In describing 600 qualities, Blank went on to say, “...the 600 is perfectly centered in a marketing plum. It’s not over-teched, and you get more bang for your buck.”

There are reasons for this. Since 750s arc the basis for Superbike, they get all the aluminum and fancy features that go with a racer-replica. That means expense. Being big, they are also heavy. Design of 600s is differently driven. The 750 offers maximum performance at any price, but 600 design seeks performance at the lowest price. Therefore 600s have had steel frames and simpler, easier-toproduce engines. Where Yamaha’s YZF750 has five valves, the Yamaha 600 has four. Where Honda’s RC45 has fuel injection and four cams, its 600 F3 has carburetors and two cams.

Yet intense competition has driven the performance of 600s so hard that they now closely rival the 750s. In Daytona Supersport practice, Duhamel’s Honda 600 was seen to pull past Fred Merkel’s 750 Supersport Suzuki. While neither of these machines is completely stock, it’s clear that Blank is right-600s have more hang for the buck. Mike Fiale, on another factory Honda, actually topped early 750 Supersport practice times.

There’s another point to be made here. Production motorcycles have become pretty tubby and riders have had to accept this. Or have they? The 600s are cheaper than their fancier big brothers-and they are closer to human scale, closer to a size that obeys the rider, not just the machine’s own momentum. Like Yamaha’s long-popular RDs, part of the 600s’ appeal, therefore, is their lighter weight and easier handling. Many times Honda team riders have been quoted in the press as saying things like, “Just make my Superbike handle like the 600 and I’ll be happy.” Miguel Duhamel’s favorite machine was for a long time the 1991 CBR600F2.

Many people now feel that 750s have become overspecialized and too far from the reality of the street. While a Daytona or Suzuka-bound 750 in full titanium-and-carbon-fiber regalia is fascinating, it is nothing like a street motorcycle in performance or price. Superbikes are in danger of becoming four-stroke grand prix machines.

Here, for 600s, is the “NASCAR effect” that Blank spoke of: The track vehicle is recognizably and closely similar to the street vehicle, bringing spectator and racing closer together. And in 600 supersport as the class now exists, the only non-standard parts permitted by rule are the exhaust system, brake pads, carburetor metering parts, front and rear springs, and the rear suspension unit. Everything else-pistons, cases, head, chassis, wheels, con-rods, anything you care to name-must be stock (tires must conform to DOT standards, hut are constructed with racing rubber compounds).

This makes the level of performance now attained by 600s all the more remarkable. Honda’s U.S. racing manager, Gary Mathers, says, “The 600 (in supersport trim) is where our raeebike (RC30) was (in power per displacement) two years ago, and that’s incredible.”

Honda’s original CBR600 of 1987 was a remarkably well-balanced machine, and each of its subsequent competitors has improved upon that standard. Without the power saturation of the 750s, 600 design must rely more on other qualities. Like racing 125s and 250s, a 600 displays higher corner speed than do bigger bikes. Being as balanced and refined as they are in handling, 600s encourage top riders to slide both wheels. As I watched Russell toss his Kawasaki ZX-6 through the infield during practice, I thought to myself, “That motorcycle is just his dancing shoes. It’s not in charge-he is. He can make it do anything he wants.” In practice, 1 watched Russell’s ZX-6 break away in the East Horseshoe, where it used the cooler right side of its tires. He just let it smoothly dissipate its excess energy, without a bobble or sudden movement. That takes confidence-and confidence comes from predictable handling and traction.

How stock is stock? We can’t know. The AMA’s post-race teardown is, understandably, not public. We must assume that the machines arc as stock as AMA wants them to he. However, we also know that at least some of the top engines come in boxes from Japan, where they are built by the same people who control the production process, who define the non-published dimensional limits for parts. How much parts variation is there? It's expensive to make parts right-on, so there’s a fashion now for relaxed dimensioning. A good fit is achieved by the time-honored process of selective assembly. Private builders scour through as many parts as they can lay their hands on, searching for heads with the best-flowing ports, for rods that are a little on the long side, pistons maybe a bit taller, cams ground slightly on the generous side. The bigger the pile of parts you have available, the more likely that you can assemble something nice-something with a little extra compression, a few degrees more valve duration, a rev box with a slightly higher limit. The factories have the biggest parts piles of all.

Or. if you are not a trusting soul, you can imagine that dimensional limits are knowingly stretched, or that casting cores sometimes shift more by intention than by accident. Steering geometry can be brought closer to optimum by “a little accident” that happens to bend either the fork tubes or the steering head. Even without all this, the stock machines deliver wonderful performance, and the thoroughly massaged works-prepped 600s are truly dazzling.

Is it hard to keep 600s in tires? Not difficult, said Dunlop’s Jim Allen. Despite being nearly as fast as 750 supersport bikes now (and in some cases faster), the 600s are lighter, which makes tire life easier. Daytona rubber on the 600 DOT tire does the job.

The 600 race failed to produce the anticipated battle between Russell and the army of HRC Hondas led by Mr. 600 himself, Miguel Duhamel. Russell’s stunning pole laptime of 1:56.28 would have put him 24th on the Superbike grid, and he and Duhamel were the only 600 riders in the 1:56s. The next quickest rider, John Kocinski on an Erion/HRC Honda, qualified at 1:58.17. Big difference. Sadly, Russell’s Kawasaki slowed on lap one, and then stopped, with undiagnosed problems. Shortly after, there was a red flag. But Russell was out. Instantly after the restart, Duhamel pulled a two-second lead that was never challenged. After the race, he would comment that the tires remained prime for only three laps, so he knew he would have to knock out the opposition right at the start. He did. Behind him, a tight peloton formed, in which close-drafting kept riders together but places changed ceaselessly. As in bicycle racing, to fall back from the group was to fall back forever. Only in the collective draft could the speed be maintained. At the end, it was three Hondas, a Kawasaki, and another Honda-Duhamel, flawless up front, with Kocinski, Hale, Steve Crevicr, and the Austrian rider Christian Zwedorn making up the top five.

You ask, “What next for 600 supersports?” Pure economics makes it essential for the factories to commit major resources to winning class honors. The racing is closer than anything else now in view. In the past, the ladder to Pro status was the 250, but today it is the 600, thoroughly supported by the grass-roots of racing in all regional associations. Both the European Championship and the GP support class are now 600-based. which puts the class into consideration as a model for any future, major class. Superbike displacement has been cut before—from I025cc to 750cc back in 1982-and it might be cut again.

Scott Russell himself said during race week, “Who knows? Maybe the 600s will be the premier class sometime down the road.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontDoin' the Wave

June 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsDucks Unlimited

June 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCAlloy Connection

June 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupBandits Coming Soon To Your Neighborhood

June 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Surprise Single

June 1995 By Robert Hough