VICTORYVISION

From the Midwest, a world-class touring machine

KEVIN CAMERON

CW EXCLUSIVE

WHEN YOU MAKE A DEAL, IF THE other party agrees too easily, you know you've overlooked

something. So it is with styling. If eveiyone loves it, the designer knows it’s too conventional and has nothing left for tomorrow.

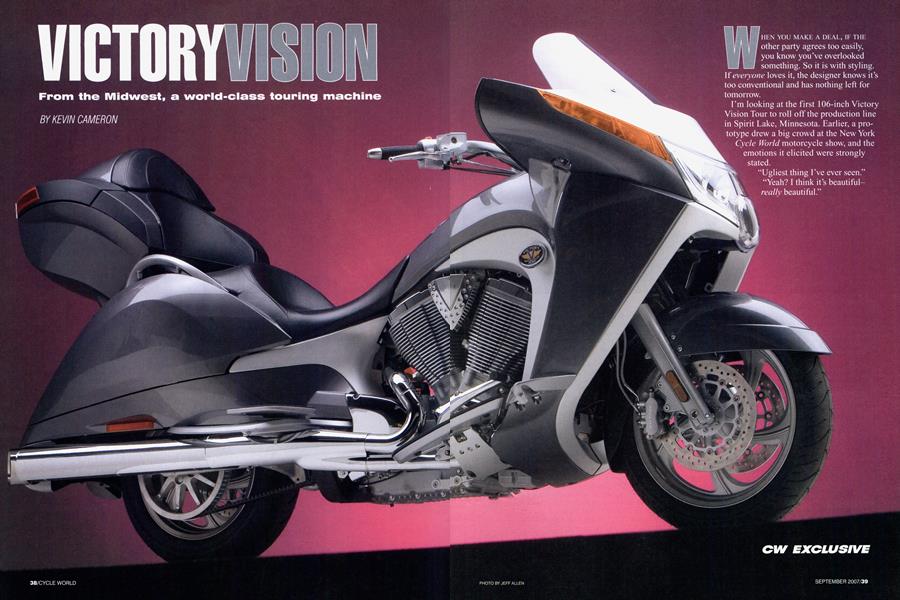

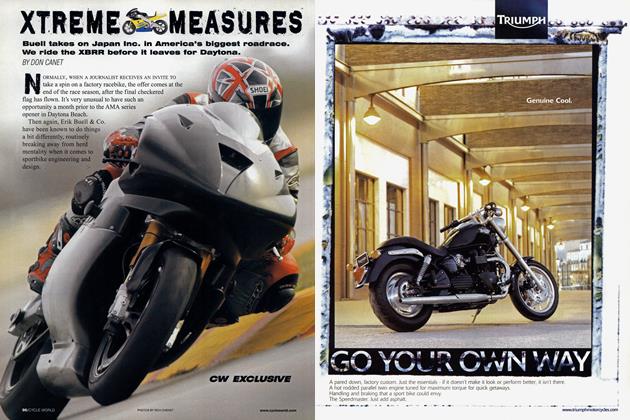

I’m looking at the first 106-inch Victory Vision Tour to roll off the production line in Spirit Lake, Minnesota. Earlier, a prototype drew a big crowd at the New York Cycle World motorcycle show, and the emotions it elicited were strongly stated.

“Ugliest thing I’ve ever seen.” “Yeah? I think it’s beautifulreally beautiful.”

Its flowing, streamlined shapes were straight out of a time when the words “modern” and “progress” could be taken seriously. I welcomed Victory’s gamble, for it opens many new avenues in American motorcycle style. And, in this era of off-shoring, it is made in the USA.

Six months later, I sat in a barbecue restaurant on a spring evening, surrounded by the corn and soybean agriculture of the American Midwest, talking with Greg Brew and Mike Song, two designers from Victory’s parent company, Polaris. They explained that Victory’s analysis divides the market into four basic attributes: Modern styling versus traditional; import versus American. One of those quadrants-that for American motorcycles with modern styling-was empty.

The Vision has been planned to fill that quadrant. The competition-Harley-Davidson and the emulators-has most thoroughly filled the traditional/American quadrant.

We finished our ribs but not our subject: product design and positioning. This would be a long and fascinating discussion of what is now called “ID,” or Industrial Design. How strange, I thought, to find a community of designers employed by hard-headed and stubborn Midwesterners. Two basic ways to sell a product are 1 ) the commodity approach, which is how pipe fittings-and near-identical sportbikes-are sold; and 2) by direct appeal to the buyer’s emotions, through styling, tradition and artfully presented legend.

“They say everything’s been done, every possible shape drawn,” Brew remarked. “But that leaves the question of coherence. What does the shape say to us?”

I thought about that. We all know the letters of the alphabet, yet we can still say things that have never been said before. Isn’t it so with style?

What does a product say to us, the non-specialists? Traditional Ameri-styled bikes aren’t really coherent messages. They are collections of individual elements such as tanks and fenders, each carefully shaped and colored. Can styling aspire to speak in complete sentences?

Visual associations are powerful. They don't ask permission to influence our thinking. When I search for an automotive analog of what Harley-Davidson has achieved I think of my uncle’s pale cream and green 1948 Buick convertible. That big car, with its uniquely purring Straight-Eight engine and dark red leather upholstery, was grand and yet comforting-telling us, “It’s good to be an American. It’s good to be here, gliding in the dignity and confidence of a secure age.” Don't we all wish. Yet industrial design can, through its power of association, give us islands of calm. My uncle’s Buick is gone, but similar powers remain, waiting to be invoked.

The Polaris design team worked with the ideas of “longand-low,” “streamlined” “graceful” and “beautiful.” For sportbikes, “modern” now means angular jet-fighter shapesthe violence of breaking the sound barrier. That is the opposite of comfortable. Therefore the Vision’s design presents the engine surrounded by grace, “a jewel in its setting,” for riders have insisted that the engine be the visual center of all. It is encircled by a sweeping, coherent curve that has been made a signature feature of all current Victory models.

ID has ambitions beyond pleasing shapes, which can be dismissed as “Christmas wrapping” or “covers” bolted onto a practical product for marketing reasons. ID seeks also to explore every aspect of user ergonomics and practicality, to make living with and using the product convenient and rewarding.

Then there’s the “Cadillac Problem.” Victory’s demographic is younger than Harley’s, but what future can your product have if the customer base grows too old to buy again? I see the furious patriarchs on their two-

wheel missions, white beards whipping in the wind. Then I think of the

once-plentiful industrial jobs that bought motorcycles for younger men with younger tastes. Old men are not the only ones with money to spend, but they are an easier sell for tradition. Find the product “hole,” define the buyer and his/her needs and tastes, and you have outlined your task. Victory did not want to manufacture a derivative product.Victory customers would choose this machine for itself and its unique qualities.

Greg Brew has been around-with BMW in Germany, lofting at Fiat in Italy, drawing aircraft interiors in California. Both Brew and Song trained and worked at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. With them at the Polaris design center are many other capable draftsmen, clay modelers and computer specialists. They have found that nothing works as well to stimulate thought as clay models-despite the fact that direct-to-foam-mill computer methods are admired elsewhere for their apparent speed. Having a solid, three-dimensional object to consider provides the information a human mind can most easily use. Brew spoke of Victory honcho Mark Blackwell running his hands over the clay Vision a hundred times in his process of making friends with the shape.

How do you assemble and keep such a creative group in the land of row-crop farming? You load them with the responsibilities that their skills deserve, and through their work they become a design community-a university. Minneapolis, a cosmopolitan city, is less than an hour away. Money that can scarcely afford slab housing in California gets you a whole farm here, and room for everything. One man-now Polaris’ top clay modeler-was commuting hours to another firm in Detroit so his family could live under a big sky.

“Come to us, we’re 15 minutes away,” offered the Polaris team. He accepted.

The morning after our dinner, I drove up to the two-yearold, $25-million Polaris Product Development Center in Wyoming, Minnesota. I was presented with an embarrassment of riches-14 engineers and managers who had worked on all parts of the Vision program. In the “war room” with us was the first machine off the line and a no-bodywork build for discussion and illustration.

Their goal was to design the outstanding machine in its class. That began with baselining competing machines, rating each in many categories. Customers judge comfort and beauty as near-equals. Comfort means freedom from noise, vibration and road irregularity. Riders want a low seat height from which a touring machine’s not inconsiderable mass can be easily handled, and Victory R&Ders set themselves a 26'/2-inch goal, the industry’s lowest. How do you combine that with enough rear-suspension travel to achieve the necessary isolation?

The answer is completely modern. Sportbike chassis are cast, giving complete control over metal thickness everywhere. The Vision’s chassis is cast for the same reason, and made in two pieces. A hollow front beam forms the steering head, tapering as it extends aft over the engine’s two mighty square cylinder heads, fastening to them via steel plates to form a rigid backbone structure like that of the classic Vincent or John Britten’s V-1000. The rear chassis element had to dip down ahead of the rear tire to accommodate the desired seat height, 4 inches of seat foam and the planned plush 5 inches of rear wheel travel. This “Z-beam” attaches to the rear of the engine and gearbox, and bears machined pads for location of major bodywork elements. Touring riders admire fit and finish as much as car owners do. When body elements bolt to welded structures, assembly requires shim stacks to correct panel alignment. Machined pads on cast structure achieve alignment automatically.

Just as in MotoGP, competition for space has forced the rear suspension unit downward, operating via pushrod and rocker through a hole in the swingarm’s forward structure. Primary springing is by conventional steel coil, with additional preload applied by compressed air.

Bending and torsional stiffness of tubes increases fast with diameter, which is why aircraft fuselages are thin, largediameter single tubes. The large cross-section of Vision’s chassis elements yields maximum stiffness, an important element in responsive steering, in the same way.

Low seat height is not the only necessity for confident control of a big bike. It must also be narrow across the knees, giving the rider maximum leg leverage when stopped. Yet the tall engine needs a bulky airbox and large fuel capacity. On the Vision, the large over-engine chassis beam is the airbox. Remove the forward-mounted air filter and look aft into the beam to see the engine’s intake trumpets. What appears to be the “tank” is actually occupied by infotainment, incidental storage and engine instrumentation. The fuel, a full 6 gallons to permit serious cruising range, is carried in a pair of aluminum tanks, located on either side of the steering head, invisible within the body-

work. Fill is from a normal cap on the right, concealed by a locking lid.

Bikes occasionally get dropped. Embarrassment adds to personal or mechanical damage. Can’t engineering save us from this? The Vision is equipped with front and rear antitipover struts, integrated into its bodywork high up to permit desired cornering clearance. An eye-popping test video shows drops from vertical and smaller angles. The bike crashes onto its struts.. .and stops there.

Helmet buffeting can be caused by turbulence shed off the top and sides of the windscreen. I was shown a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) animation of this, a huge wake of flame-like vortices being shed as a simulated machine advances. Windscreen height is adjustable on a four-bar linkage over a range of 4 inches to place occupants’ helmets in turbulence-free air. For those above or below average height, taller and shorter windscreens are optional.

Engines are hot. Summer engine heat-rejection can cook rider and passenger. Two adjustable spoilers are provided, one on either side just beneath the handlebar fairing. In one position, they deflect side airflow away from the rider(s). Turn it in the other direction and air flowing around the nose of the machine is permitted to cool the rider.

With engine as chassis structure, vibration control is central. Every body panel vibrating in sympathy radiates sound. Engine exhaust note can be pleasant-the rumble of a V-Twin or the growl of a WWII radial-but meaningless noise just makes us tense and more tired than we’d like to be at the end of the day. Silence is golden.

Goals for the engine and driveline included providing Harley-beating performance while retaining stump-pulling “cruiser torque,” along with a luxurious absence of noise. The torque of traditional cruisers peaks at very low rpm (like 2500!) but then, throttled by modest valve area and timing, it slopes downward as revs increase. With the Victory engine’s four valves per cylinder, high torque at low revs is easily combined with airflow that remains generous all the way to peak.

Victory also says performance is “class competitive” with Japanese (Honda) and European (BMW) tourers, though it’s unlikely that means matching the 100 horsepower each of those Multis puts out. One key to this is just as it was back in the day of Indian’s famed Powerplus engine-low valve overlap that preserves good air-pumping to even the lowest rpm. Yet thanks to the large flow area of paired inlets, Victory is able to keep that high torque constant as rpm builds. The result combines hard cruiser-style pull from the bottom with ample power for high-speed passing in the wideopen spaces.

When you make power, you make heat. About two-thirds of Victory’s cooling takes place through the fins on its large cylinders. The other third is handled by oil, circulated through a cooler. All four-valve engines have a critical region between their paired exhaust valves-the so-called “exhaust bridge’-potentially troublesome because it is heated from both sides. Some designs seek to avoid the problem by spacing undersized exhaust valves far apart, but in the Vision engine this region is strategically cooled by highspeed oil circulation through a .2-inch passage in the bridge. High-flow turbulence delivers maximum cooling but picks up maximum heat energy. This oil, after its rush through the exhaust bridge, falls back down the cam-chain tunnels to the sump below.

The Polaris development center contains the dynos, build rooms and emissions equipment you would expect. Engineers monitor big screens presenting data as engines and complete bikes hum through their test cycles behind multiple glass panels.

Flexible mounting can deal with engine vibes, but denying use of the engine as structure requires extra chassis structure and weight. Better to balance all shaking forces that can be balanced and to reduce those that cannot by making reciprocating parts as light as possible.

Finite element analysis backed by physical testing has slimmed the two side-by-side plain-bearing con-rods and the forged, short-skirted, three-ring pistons to state-of-the-art lightness. When the remaining shaking force of a narrowangle V-Twin is balanced 50 percent by crankshaft counterweights, the resultant is a nearly constant imbalance force, rotating backward at crank speed. This, in the Vision as in other Victory models, is zeroed-out by adding a counterrotating balance shaft. Part of the presentation was an animated engine, all parts in motion, and there was the balance shaft doing its good work.

Modest secondary imbalance forces remain, arising from the twice-per-revolution con-rod angling-whose analog is as our own rising and falling twice per right/left stride cycle as we walk. Their amplitude is greatly reduced by the lightness of the reciprocating parts and by the engine’s Vee angle. Its 50 degrees is very close to the 60 degrees at which secondary vibes become self-canceling.

There are other sources of sound and vibration. But where are they? A mathematical

technique called Fourier Analysis allows a complex waveform to be separated into its constituent parts, each of which can then more easily be traced to its source. At cruising speeds, tooth engagement frequencies in the gearbox were exciting surfaces into significant sound radiation. The sound subsided when the tooth numbers were changed. The large acreage of the primary cover was another rich sound source. Its natural vibratory modes were pushed up, out of hearing, by extensive internal ribbing. When I knocked on it with my knuckles, it was as acoustically dead as a piece of wood.

These engineers are constantly riding the motorcycles they design, frequently over long distances. One described the typical outbursts of his colleagues as they arrived late on early prototypes, one by one, at the Victory “safehouse” at Sturgis.

“That’s the last time I’ll ever put up with the bump on that whatsit-it’s right where my ankle goes!”

There’s nothing like 10 hours in the saddle to truly put engineers into the state of mind of the riders they serve.

Modern product planning is a rich process, and Victory has given us a rare and candid look at it. No matter what efforts are made, it cannot be risk-free. Success requires a very confident wager that the public will confirm the positioning, styling and engineering. Production lines roll, showrooms open and you, the people, make the crucial decisions.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAnatomy of A Black Eye

September 2007 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Trip To the New Barber

September 2007 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTechnology Duel

September 2007 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2007 -

Roundup

RoundupSmaller, Lighter, Faster

September 2007 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

Roundup2008 Street Trip

September 2007 By Blake Conner