Getting started

TDC

Kevin Cameron

THE STARTING OF A MOTORCYCLE CAN be routine or it can be theater. It can be ridiculous or sublime. A well-tuned machine of the 1960s would start within a few kicks. But common trouble could transform the attempt into an exhibition of muscle, swearing and frustration. Are the throttle slides worn and loose? Has moisture impregnated the paper bearing insulating cups of the magneto? Have the points closed up?

Brando-boys of the period liked to park their tiny-tanked Sportsters in front of the Ebbtide Lounge, just north of Boston. It was important to leave the front wheel rakishly turned to the right, to contrast with the radical left lean of the sidestand. After last call, the battle of the magnetos would begin. The drill was to heave the machine upright, carefully balance it, throw oneself high into the air, and come down with a whoof on the kickstart lever. It was correct to pause between leaps to readjust the timing or to twiddle the throttle. People gathered to watch the ritual. Forces were now brought to fine balance, creating high drama. The machine owner felt the expectant stares of the onlookers, and he also felt the ebbing of his own endurance, as kick followed exhausting kick.

In time, a favorable accumulation of fuel might occur in the branched intake manifold. That might couple with a particularly energetic kick, extracting a spark from the FairbanksMorse tractor mag. With a mighty rumble, the beast would spring to life. Or the kicking might continue until the crowd shredded away, leaving the rider alone with his problem.

For myself, peak starting ignominy came in the summer of 1967. I pushed my TD1-B Yamaha racebike the length of the Mosport starting grid and down into Turn 1 without so much as a pop. The engine usually fired just as my legs turned to pudding, and just as I could hear the field coming behind me to complete lap one.

The sublime opposite was to see Mr. S.M.B. Hailwood push-start the Honda 250 Six at that same racetrack, that same season. One, two, three steps and he dropped the clutch at the same instant that his thigh hit the saddle. A shocking wall of sound blasted us as the engine sprang to peak revs, and Hailwood was rocketed into Turn 1.

Today, of course, running-engine clutch-starts are used in roadracing. When you see it done right, one rider somehow forges steadily ahead of all the others who are trying just as hard. Despite the noise and smoke, he plays the clutch to reach peak thrust.

Just a few years ago, Dr. John Wittner started his Pro-Twins Moto Guzzi on the grid with a detachable starter and battery cart-just as IndyCars are started. Insert the starter at the side of the crankcase, brace yourself against the torque reaction, and hit the button. Why? Racing engines with great big cylinders strongly resist being started by any means. Even with rollers, the start-up of a Twin includes the danger of either snapping or fatally weakening the drive chain during the first few violent sneezes. Four-cylinder 750 racebikes, which compress less than half as much air at a time, can almost always be started casually with a short push.

Electric starting is a convenience on the street, and has brought the pleasures of motorcycling to many who prefer not to pit the strength of one leg against cold oil, high compression and reluctant sparks. Who can blame them? On the other hand, where is the theater in pressing a button? Ah, yes, but see what it’s done for fashion! Kickstart levers demand sturdy shoes or boots, but starter buttons invite a wider range of fashion statement-loafers, tennies, even go-aheads.

Before slipper clutches came to drag racing, the slip occurred between tire and pavement, causing the billowing rubber smoke seen in vintage drag videos. Then someone had the idea of building a giant go-kart clutch that would partially disengage if the tire bogged the engine. This made largely smokeless starts possible, keeping the tire at a rate of slip that gave maximum drive, and holding the engine close to peak torque-automatically.

Still, I remember admiring a wellridden Triumph Bonneville at a longago New York state strip. The rider had a fine clutch hand; the front wheel hovered about 3 inches off the ground through two-and-a-half gears, keeping maximum weight on the drivewheel when it was important-very nice. Today, GP bikes carry systems that limit torque in lower gears, to prevent flipping over backwards. That’s why the big wheelies of the early 1980s are seen no more on the grand prix circuit. As in drag racing, the riders have better uses for that power.

Despite the changes that technology has brought, the start-up of any machine still contains muted drama. The engine fires and you feel its vibration, hear its exhaust. You hear the valvetrain-either the subdued white noise of overhead cams or the knitting-needle clicks as hydraulic tappets zero their clearances. Gear whine rises and falls with rpm, as hundreds of teeth rush together every second, each contact contributing a tiny spike of sound. You can imagine the oil making its way through the galleries, like returning blood warming your hands when you come in from the cold. You may hear the running clearances “speak” briefly before the oil arrives to fill them, cushioning the motions of the pistons, rods and crankshaft. This sound disappears in the first few revolutions, but it reminds you that there is machinery under the civilized exterior of paint and plastic.

In my imagination, I recall all those who lived with less civilized machinesthe sweating oilers in ships’ enginerooms, the locomotive engineers and the leather-clad, begoggled motorists at the turn of the century-who worked with great vibrating masses of metal, whirling and slamming backward and forward, so that the present uses of such motions could become so convenient and so effective. É3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontWales Watching

February 1994 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsRushville Revisited

February 1994 By Peter Egan -

Letters

February 1994 -

Roundup

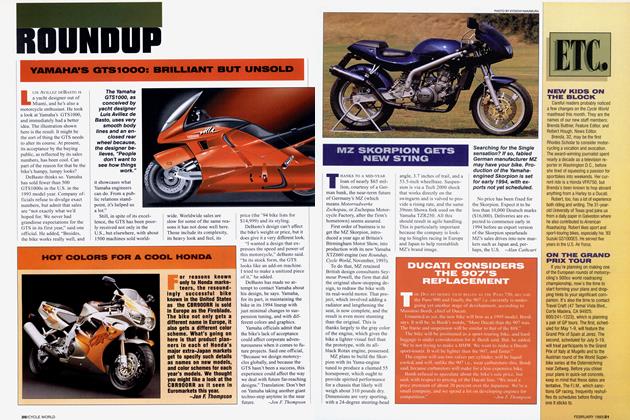

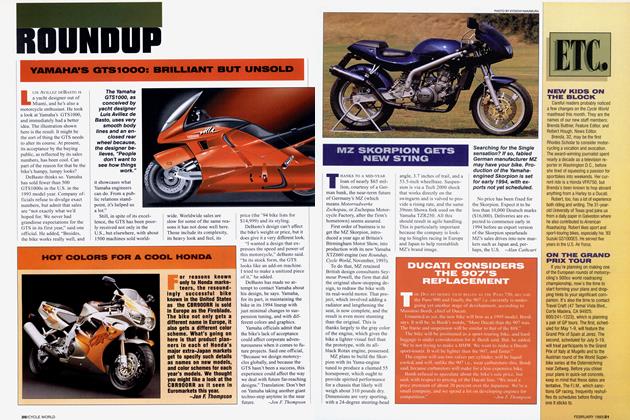

RoundupYamaha's Gts1ooo: Brilliant But Unsold

February 1994 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupHot Colors For A Cool Honda

February 1994 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupMz Skorpion Gets New Sting

February 1994 By Alan Cathcart