Wales watching

UP FRONT

David Edwards

SOMETIMES A TOURING RIDER’S BEST friend-after an electric vest and a good set of raingear-is serendipity.

I was reminded of this last summer during a week’s riding vacation in Wales. My friend Charles Davis and I had talked of riding around the British Isles since college days, the original plan being a rorty three months aboard used Triumphs. Fifteen summers later, about all either of us could squeeze away from work was a week.

“Look, we’ll just tour Wales,” Charles said. “I’ll cash in some frequent-flyer miles and take care of the tickets. You arrange the bikes.”

Wales, smaller than Massachusetts, perches on England’s west side, part of the United Kingdom but fiercely independent. This trait is driven home at the Welsh-English border: “Croeso i Gymura Welcome to Wales” reads the bilingual roadsign. Writer David Yeadon in a recent issue of National Geographic Traveler described Wales as a “pure vortex,” explaining, “It sucks you in, dazzling you with its wondrous, kaleidoscopic whirl of towering mountain ranges, ragged, wavepounded peninsulas and gentle green valleys; its ancient culture and tangled, embattled history; its castles, stately homes and museums....”

For touring motorcyclists in late August, Wales also offers temperatures in the 60s and 70s (it can get colder and it can rain), lightly trafficked backroads (remember they drive on the wrong side of the road) and friendly pubs in quaint stone villages (only after the bikes have been parked for the night, of course).

BMW was nice enough to lend me an R100GS Paris-Dakar-my favorite backroad touring bike-and Harley chipped in with a well-kept FXR Low Rider, liberated from the used-bike fleet of the good folks at Surrey Harley-Davidson. By the third day, however, the FXR was giving us some gruff, leaking a small but constant amount of oil from the primary cover, which was coating the rear tire. None of the Allen wrenches in my toolkit fit, so we couldn’t snug the cover up to stem the flow. We stopped at a gas station in the harbor town of Pwllheli to use their spray washer and borrow the proper Allen wrench. The clean-up went nicely, but all the shop had were

metric Allens. It was then that we met Trevor Sharp, a short, wiry man with a handshake of Visegrip proportions. Turns out the likable Sharp was mechanic to GP stars Barry Sheene and Steve Baker in the 1970s, and wasn’t going to let us leave his town without a buttoned-down primary cover.

He rooted through the shop’s toolboxes until he uncovered the appropriate wrench, applied serious torque to the offending bolts, smiled, shook our hands and sent us on our way-but not without a parting bit of advice.

“If you’re going anywhere near Sam,” he said, “you should stop in and see Jerry Cartwright. He builds Tritons.”

Describing Jerry Cartwright merely as a Triton builder is a little like saying Leonardo de Vinci painted a few portraits in his time. Cartwright, exmerchant marine navigator, is more like an artist who uses Norton Featherbed frames and Triumph T120 engines as his canvas. Onto this basic framework he hangs an alloy fuel tank, a hump-back seat, Akront rims, a Grimeca 4LS front brake, clip-ons and rearsets to form the classic caferacer. The finished product is so fine that Cartwright has been inducted into England’s Guild of Master Craftsman. “Now if someone steals my ideas, I don’t have to sue them,” he’s fond of saying, “the Queen does.”

We tracked down Cartwright at his farmhouse, where the Low Rider was immediately put to use as a photo prop for a local lass who was shooting

her modeling portfolio in Cartwright’s pasture. There are worse ways to relax after an afternoon ride than sipping a cup of Mrs. Cartwright’s tea as a nubile young thing in various states of undress drapes herself over your bike for a photographer.

Our contribution to future fashion photography complete, Cartwright told us about his business, Peninsula Classics. Thirty-six Tritons have rolled out of the company’s weathered wooden workshop since Cartwright opened doors in 1988. Working by himself, he completes a pair of Tritons every three months, and he doesn’t like to be rushed. “Every time I get too many orders, I raise the price £1000,” Cartwright says. Five years ago a Peninsula Triton cost £3000; today £8000 ($12,000) brings one home.

Cartwright’s personal bike is a Harley Sportster 883. “I figured if you Yanks could put a man on the moon, you could build a decent motorcycle. I was right; I’ll never be without one now,” he says. “Besides, around here it’s not how fast you can go ’round a corner, but how fast you can stop for the 50 sheep on the other side.”

With that, Cartwright took us on a quick tour of the surrounding Lleyn Peninsula, bending the 883 into turns at 70 mph, before saying goodbye and getting back to work. That night over pints of bitter at our hotel’s bar, I told Charles, “That may be the best day I’ve ever had on a bike.” And all because of a chance encounter in a town with too few vowels in its name.

The point here isn’t profound, but it is worth reiterating. Touring is more than racking up miles, more than reaching destinations. As much as anything, touring is a state of mind. Remember to pack your curiosity and your sense of adventure, get a bike and get outta town. □

Speaking of getting out of town, Cycle World and Edelweiss Bike Travel are putting on another GP EuroTour. This year, the German GP is our destination after a week of riding in Austria, Switzerland and Germany’s Black Forest. Dates are June 5-13, with the tour package (airfare, bike rental and lodging) starting at $2395. For more info, contact Armonk Travel at 800/255-7451.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Leanings

LeaningsRushville Revisited

February 1994 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCGetting Started

February 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

February 1994 -

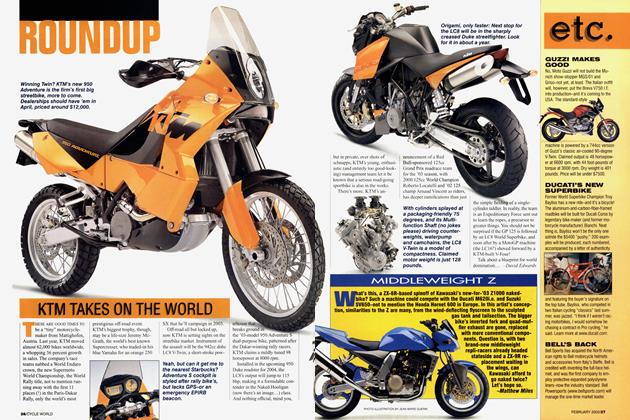

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Gts1ooo: Brilliant But Unsold

February 1994 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupHot Colors For A Cool Honda

February 1994 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupMz Skorpion Gets New Sting

February 1994 By Alan Cathcart