Anatomy of a black eye

UP FRONT

David Edwards

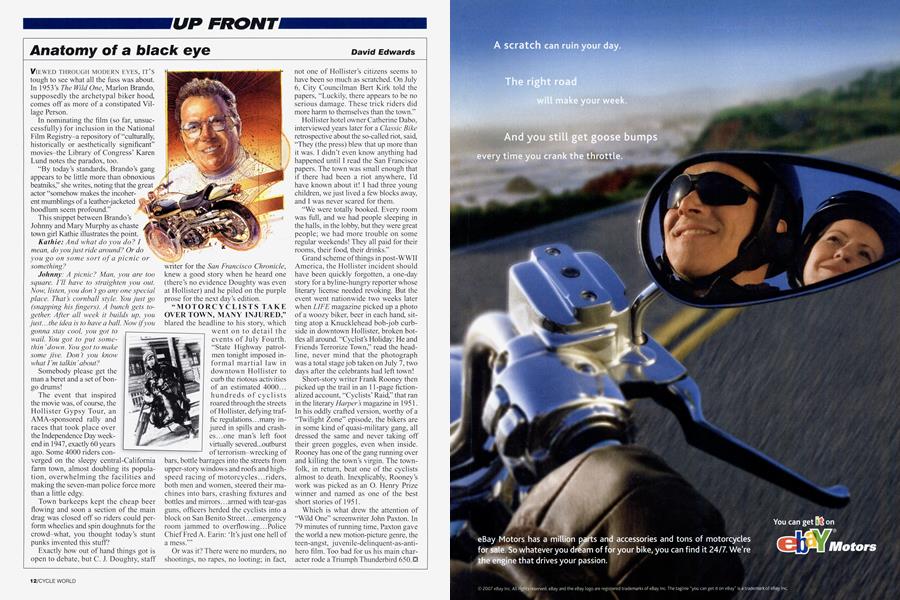

VIEWED THROUGH MODERN EYES, IT’S tough to see what all the fuss was about.

In 1953’s The Wild One, Marlon Brando, supposedly the archetypal biker hood, comes off as more of a constipated Village Person.

In nominating the film (so far, unsuccessfully) for inclusion in the National Film Registry-a repository of “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant” movies-the Library of Congress’ Karen Lund notes the paradox, too.

“By today’s standards, Brando’s gang appears to be little more than obnoxious beatniks,” she writes, noting that the great actor “somehow makes the incoherent mumblings of a leather-jacketed hoodlum seem profound.”

This snippet between Brando’s Johnny and Mary Murphy as chaste town girl Kathie illustrates the point.

Kathie: And what do you do? I mean, do you just ride around? Or do you go on some sort of a picnic or something?

Johnny: A picnic? Man, you are too square. I’ll have to straighten you out. Now, listen, you don’t go any one special place. That ’s combad style. You just go (snapping his fingers). A bunch gets together. After all week it builds up, you just... the idea is to have a ball. Now if you

gonna stay cool, you got to wail. You got to put somethin ’down. You got to make some jive. Don’t you know what I’m talkin 'about?

Somebody please get the man a beret and a set of bongo drums!

The event that inspired the movie was, of course, the Hollister Gypsy Tour, an AMA-sponsored rally and races that took place over the Independence Day weekend in 1947, exactly 60 years

ago. Some 4000 riders converged on the sleepy central-California farm town, almost doubling its population, overwhelming the facilities and making the seven-man police force more than a little edgy.

Town barkeeps kept the cheap beer flowing and soon a section of the main drag was closed off so riders could perform wheelies and spin doughnuts for the crowd-what, you thought today’s stunt punks invented this stuff?

Exactly how out of hand things got is open to debate, but C. J. Doughty, staff writer for the San Francisco Chronicle, knew a good story when he heard one (there’s no evidence Doughty was even at Hollister) and he piled on the purple prose for the next day’s edition.

“MOTORCYCLISTS TAKE OVER TOWN, MANY INJURED,” blared the headline to his story, which

went on to detail the events of July Fourth. “State Highway patrolmen tonight imposed informal martial law in downtown Hollister to curb the riotous activities of an estimated 4000... hundreds of cyclists roared through the streets of Hollister, defying traffic regulations...many injured in spills and crashes... one man’s left foot virtually severed...outburst of terrorism-wrecking of

bars, bottle barrages into the streets from upper-story windows and roofs and highspeed racing of motorcycles...riders, both men and women, steered their machines into bars, crashing fixtures and bottles and mirrors.. .armed with tear-gas guns, officers herded the cyclists into a block on San Benito Street.. .emergency room jammed to overflowing...Police Chief Fred A. Earin: ‘It’s just one hell of a mess.’”

Or was it? There were no murders, no shootings, no rapes, no looting; in fact, not one of Hollister’s citizens seems to have been so much as scratched. On July 6, City Councilman Bert Kirk told the papers, “Luckily, there appears to be no serious damage. These trick riders did more harm to themselves than the town.”

Hollister hotel owner Catherine Dabo, interviewed years later for a Classic Bike retrospective about the so-called riot, said, “They (the press) blew that up more than it was. I didn’t even know anything had happened until I read the San Francisco papers. The town was small enough that if there had been a riot anywhere, I’d have known about it! I had three young children, we just lived a few blocks away, and I was never scared for them.

“We were totally booked. Every room was full, and we had people sleeping in the halls, in the lobby, but they were great people; we had more trouble on some regular weekends! They all paid for their rooms, their food, their drinks.”

Grand scheme of things in post-WWII America, the Hollister incident should have been quickly forgotten, a one-day story for a byline-hungry reporter whose literary license needed revoking. But the event went nationwide two weeks later when LIFE magazine picked up a photo of a woozy biker, beer in each hand, sitting atop a Knucklehead bob-job curbside in downtown Hollister, broken bottles all around. “Cyclist’s Holiday: He and Friends Terrorize Town,” read the headline, never mind that the photograph was a total stage job taken on July 7, two days after the celebrants had left town!

Short-story writer Frank Rooney then picked up the trail in an 11-page fictionalized account, “Cyclists’ Raid,” that ran in the literary Harper’s magazine in 1951. In his oddly crafted version, worthy of a “Twilight Zone” episode, the bikers are in some kind of quasi-military gang, all dressed the same and never taking off their green goggles, even when inside. Rooney has one of the gang running over and killing the town’s virgin. The townfolk, in return, beat one of the cyclists almost to death. Inexplicably, Rooney’s work was picked as an O. Henry Prize winner and named as one of the best short stories of 1951.

Which is what drew the attention of “Wild One” screenwriter John Paxton. In 79 minutes of running time, Paxton gave the world a new motion-picture genre, the teen-angst, juvenile-delinquent-as-antihero film. Too bad for us his main character rode a Triumph Thunderbird

View Full Issue

View Full Issue