THE BEST

CW EXCLUSIVE

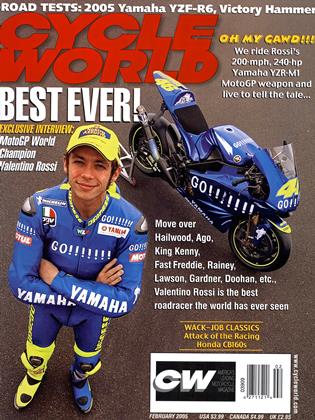

Valentino Rossi proves there's more to winning races than horsepower

KEVIN CAMERON

VALENTINO Rossi is MOTOGP WORLD Champion, switching to Yamaha at the end of the 2003 season after

winning one 500cc world title and two MotoGP titles for Honda.

His rise to greatness has been both rapid and carefu1-an., interesting combination. He took a year to learn the circuits in 125cc GP and was

champion the following year. Moving to 250s, he repeated the tactic, winning that class in 1999. On a two-stroke Honda NSR500, he came second in his first year and won the class in 2001. He has dominated the new four-stroke 990cc MotoGP class since its inception in ’02-despite opposition from several strong riders. For those who see the world in ultimates, Rossi may be the most remarkable roadracer ever.

I went to this season’s last GP, at the Circuit Ricardo Tormo in Valencia, Spain, to talk with both Valentino Rossi and his crew chief Jeremy Burgess, who came with him from Honda.

Rossi, 25, is cheerful, as if racing were a pleasure as simple as ice cream. When he wins, he speaks through a grin, his curly hair tumbling over a visor or billowing from under a cap. He speaks frankly and wittily of rider concerns. He seems like a young man with his affairs in balance, finding life and racing amusing. He radiates intelligence and humor.

Movie-makers insist that the winner is he who pushes the limit, “dicing with death.” But it was clear at Valencia that Rossi takes fewer risks than his rivals, not more. As we watched practice from the infield, CW Managing Editor Matthew Miles said, “Look, Rossi’s not spinning.” It was true-he wasn’t sliding and his bike was stable. His rivals spun, tail-wagged during braking, and even crashed.

Does he have the fastest bike? Let’s check. In the pressroom, we found that Rossi’s Yamaha was 14th-fastest, a lull 5 mph down from Troy Bayliss’ 199-mph Ducati. Scratch one theory.

Where is his advantage? As Burgess put it, “The last 50 meters of the straight (where top speed occurs) come around only once a lap, but the first 50 meters exiting a comer come around 13 times a lap.” Which would you rather improve? Rossi’s bike isn’t spinning because its torque curve is smooth enough to be accurately controlled by the rider. This allows early, strong and spin-free acceleration.

Dicing with death? Or as U.S. riders often put it, “Rahdin’ at a hunnert an’ tin percint?” Just the opposite. Burgess, a no-nonsense Australian who speaks calmly in complete thoughts without “urns” or “ahs,” told me that their goal is for Valentino to be able to win at 96 percent. In other words, they work to make the motorcycle very easy to ride fast. As a rider laps faster, he must work closer to his limits, and so begins to make increasing numbers of small mistakes. You see this on the watch as quicker but less consistent lap times. This is because the largest of the now-more-frequent small mistakes must be “gathered up.” This takes time, causing lap-time variation. Lap-time variation is a measure of the rider’s level of risk.

If we now make the motorcycle easier to ride fastsmoothing its torque to eliminate wheelspin, suppressing chatter, reducing braking instability-the rider can reach a given quick lap time with reduced physical and mental effort, and will lap at that speed with fewer mistakes and therefore in greater safety. For a given level of effort, he will go faster, shifting the hard work to his opponents, pushing them into their personal “mistake zones.”

This is important in Rossi’s success. In race after race, he shadows his leading competitor, forcing him to ride harder than he is himself. Because Rossi is usually riding conservatively at this speed, his tires age more slowly than those of his rival. When the situation ripens, he makes a pass. The competitor, frazzled from maximum effort, his tires now past their best, accepts second place. Harder men push on, and often fall.

For the estimated 6000 staffers, mechanics and riders who travel with motorcycle GP racing, change is gradual. For me, it is always a shock. In 1973, high-tech was an electric tailgate. In 1981, a few top riders had motorhomes but most lived in “caravans.” Big teams might have had a tractor-trailer as in AMA racing, but most arrived in vans. By ’97, the biggest teams had two or even three tractortrailers and a hospitality bus. Today, each major team has a row of big rigs, with at least two more to haul hospitality units. TV and outside sponsors pay the bills.

Three rows back from the pit building was “mo-ho alley”-the posh residential district. The paddock is studded with service pylons, 3-foot obelisks of power and water connections for the riders’ mega-dollar motorhomes.

As at most GPs, Valencia’s paddock building is a row of garages facing pit lane, topped by offices, permanent hospitality suites and an observation deck. Just behind it was a solid row of gleaming tractor-trailers with $50,000 paint jobs-several per major team—backed in with precise parallelism. In front of them was the paddock’s main “avenue,” across from which was the row of fancy, fold-out hospitality units. Each featured its own kitchen (the teams eat here, and compete for top chef) and bar/dining area, surrounded by hushed private offices for interviews and business. Familiar faces are admitted. Others are “screened.” I watched a leggy camp-follower penetrate the door of the Yamaha hospitality by chatting up a regular, then dropping him once inside. Half an hour later, she had schmoozed through the noisy crowd to the bar and was edging toward rider Marco Melandri. Good luck to all.

The Valencia circuit is folded to fit into a huge arena, ringed by grandstands, and any spectator with binoculars can see all parts of the track. On Sunday, a reported 122,000 people filled everything. Waves of coordinated arm-movements propagated around the stands, and the boom and drifting smoke of major fireworks were frequent. In the races, every pass was signaled by a roar.

Behind tractor-trailer row are the closed overhead and personnel doors of the garages. Mechanics wash wheels, or grind toe or helmet clearance into fairings or windscreens. Hoses and cables writhe underfoot. Look sharp; it’s easy to stumble into a tire rack-or someone famous. When a door opens, people crowd and crane to see. Riders are mobbed. The backroom holds shipping containers, shared with laptops on a table-racing’s new “adjustable wrench.” Bikes and mechanics fill the second sanctum-with light, corporate logos and equipment. In a garage I visited, the team was just finishing the daily valve-spring change, checking clearances with feeler gauges.

As I emerged onto the paddock’s “Grand Boulevard on Thursday, a familiar Japanese translator took me by the elbow. She smoothly steered me between hospitalities, past back kitchen doors, to the access stairs of one of the older units. At a table sat Honda’s Kyoichi Yoshii, current Chief Engineer, Motor Sports Development, ’04 project leader for the RC21IV. I asked him how Honda came to invert the standard paradigm of racing. For years, we have accepted that as a rider is given faster bikes, each improvement brings more power but a narrower powerband, making the bike harder to ride. At career’s peak, he is given a machine almost impossible to ride—a two-stroke 500. Honda s RC21IV flipped that idea, showing that racing machines could-and should-be made easier to ride, smoother, more predictable even than the best streetbikes.

Yoshii, who speaks English well, replied that this had been a concern at Honda for some years, and had initially prevented the company from producing big-inch high-performance streetbikes. Only when they had satisfied themselves that they could engineer high-power machines to be easy to ride did Honda produce the CBR900RR. In planning meetings, Yoshii related, the first RC21IV Large Project Leader,

Heijiro Yoshimura, had pushed the easy-to-ride concept.

When the new MotoGP class began in 2002, the Honda was immediately successful, while Aprilia, Yamaha and Suzuki, infected by large doses of alleged Formula One technology, languished in the rear. Only Ducati, in 2003, presented something of a challenge, winning a race, scoring podiums and being impressively fast.

Of the V-Five’s origins, Burgess said, “Mick Doohan had a bit of input on the 211 and was asked to comment. He rode it in August of 2001, after the Suzuka Eight Hours. We had nine major problems with it and, to their credit, Honda had fixed eight out of the nine the next time we got on it. They were really keen to make sure that bike was going to be good, because (initially) Valentino had indicated he’d like to ride his 500. That was a great challenge for the engineers-they had to prove the four-stroke was better. And when we tested at the end of that year, Valentino said to me in Jerez that we had to > have it. It didn’t pass the 500s at the end of the straight; it passed them in third and fourth gear.”

When 2003 ended, Rossi announced he was moving to Y amaha. Why, after three world championships on the dominant machine?

“Valentino decided to make the change because he needed a challenge to maintain his interest,” Burgess began. “We could see at the beginning part of last year he really wasn’t into it. He was letting Sete Gibemau get into a race with him, and then he would make a mistake and Sete would win the race.That’s not how we should be racing-we should be racing to win. And at the second half of the season Valentino came back and took all but one race and won the championship by 80 points, which is three races. I felt that the Yamaha wasn’t three Grands Prix worse than the Honda.”

This fits with what the RC211 V’s second LPL, Mr. Kanaumi, had said a year ago at Motegi, Japan: “For a journalist, the Honda appears to be much better than the Yamaha now, but for an engineer, the difference is not so great.”

Rossi may have had other reasons for leaving Honda. As money pours into the sport, it expects maximum payback from riders in the form of a grueling schedule of appearances and official functions of all kinds—including talking to me. When I brought this up, he laughed.

“I have this problem, yes, but I am lucky-I am in a good position because I win. I am able to decide how much time I want to give. And if not, if I do not make a big fight in my contract, for sure all these people want to own my day. So I always fight a lot to have my life, to have my free time.

First, it is better for me, and second, because I have my free time,' I go faster.” This is part of the reason that Rossi moved from his native Italy to London.

Rossi also spoke of the positive effect of real competition on what he repeatedly called “our sport.” He said, For sure, we changed a lot with this move to Yamaha. Before, there was only Honda-it was a race for only Honda riders.”

Race attendance this year increased significantly, which it might not have done had MotoGP remained a “Honda Cup.”

I asked Rossi about the move to Yamaha, in which he brought over not only Burgess, but also three of his technicians. “If you’re going, we’re going, too,” they allegedly said.

“When I move from 250 to 500,1 want to bring my old team, but it was impossible,” Rossi said. “After I go with Jeremy, it was better, because Jeremy is better than my old team. When I start to think of this move, this dangerous move from Honda to Yamaha, everything will be different, the bike, all the people. I wanted one point to remain the same-I wanted Jeremy.” Burgess takes up the narrative. “I think when Valentino indicated that there was not much more to achieve where he was, it wasn’t that difficult. It sort of tickled my fancy to see what would happen if we moved, and I realized we were throwing the torch on the bridge as we left, so I think that made me work a little bit harder. With the Yamaha, many times we turned a Grand Prix into a seven-day event. We’d come on Wednesday and leave on the Tuesday night of the following week. We would spend Monday and Tuesday working on the problems we d had in the practices and race, and we were able to improve the bike and take it to the next race as an improved product. The Honda, in the last couple of years, was so good that if you stayed another day, you spent the time testing tires for Michelin. There was very little you could do to make a significant improvement. I mean, it’s a very, very good motorcycle.”

I asked Valentino about riding style. Some riders try to make every machine handle like a 250. Others can change their style in practice, but in the race revert to old (and more crash-prone) habits.

“It is very important to adapt your style. If not, it is a problem,” he said. “Coming from the 250s is difficult. A lot of riders try to maintain the comer speed of the 250, but that is not possible (on the big bikes) because it is too dangerous-you are always too much at the limit, it is too easy to make a mistake. It is completely another bike and must be ridden in another way. Use the power, use the acceleration, slide, but don’t try to comer like a 250.”

As our conversation deepens, it’s clear that Rossi thinks about much more than just riding style-and that despite his legions of flag-waving fans, some written words and chatroom flak has rankled him.

“A lot of people in this paddock-my opinion-don’t understand anything about bikes, about our sport, especially in the pressroom,” he said. “Maybe 10, not more. Maybe Kenny Sr., maybe Jeremy understands this sport. For sure, on the track, MotoGP remains the same sport of 20, 30 years ago, but outside the track is another reality-and a lot of people don’t understand about the pressure, about the style, the differences between riders.”

It began to be clearer to me how two or three teams in this series could work successfully to make their bikes hook up rather than spin, while the others continue as if MotoGP were dirt-track racing.

Rossi said, “When I started with the 500,1 try the old 500, the old NSR from Mick. It was difficult but quite good to ride. When I rode the new engine that Honda prepared for Alex Criville, we had a lot of problems-the bike was very fast but it was impossible to ride.”

Why? Burgess explained. “At the end of 1999 they’d asked Criville as world champion what he wanted, and he said, 'I want more power.’ So they gave him more power-again, by narrowing the powerband-and the bike became difficult to ride.”

Rossi continued. “When after we had some good results and Honda started to pay attention to us-me and Jeremy-we try always to make the bike more easy and more easy to ride. The problem is engine delivery. We work a lot on the RC-V in the first two years on the engine delivery because this is the secret for good lap times. Maybe one lap is okay with a lot of power, but 30 laps is another story. It is the same work I did this year with the Yamaha-change engine delivery to be more sweet, more smooth because the bike first needs to be easier. And after, it needs to be faster.”

How can less power equal more performance? The harder engineers work to boost engine power-extending intake timing, fitting larger valves and ports-the more complicated (full of dips and peaks resulting from intake and exhaust wave action) becomes the shape of the torque curve. When the rider tries to accelerate out of a turn, he not only has to feed in more throttle as the bike gains grip in rising from full lean to full upright, he must also try to compensate for all the bumps and hollows in the torque curve with rapid and exact throttle movements. As Rossi observed, you can do this for one lap, but not 30.

But if the engine’s state of tune is softened, the result is less peak power and a smoother, flatter torque curve, which the rider can use to the full much more easily. Therefore with the “soft” engine, the rider is actually able to safely use more throttle during critical initial off-comer acceleration than can the rider of a more powerful bike. The result is the quick, no-spin, noslide off-comer acceleration we had seen from Rossi-and also from Max Biaggi. Once upright, the Honda definitely accelerates harder than the Yamaha, and its top speed is greater. But as Burgess points out, there are many comers and only one straightaway. Less is more.

But wait, can’t F-l-inspired gadgetry handle this? So far, no. After three years of MotoGP, not one of the “gadget bikes” has shown an advantage. In many cases, automatic systems have been set aside. Two wheels, it seems, are trickier than four.

Another question: If Honda created this “Less-is-More” design philosophy, how did Rossi and Burgess beat them with a Yamaha? To fend off Ducati, Honda added additional power this year, making the RC-V harder to ride. Also, Rossi and Burgess are the foremost track practitioners of Less is More, and Yamaha had the sense to listen to them. Less-experienced Honda crewmen lacked their level of knowledge and method. Yamaha had hoped to win three GPs in 2004, but by August it was clear that if it pulled out all the stops Rossi might actually win the title. That’s how it turned out.

What next? Honda will fight back. Heads have already rolled. When I asked for Kanaumi, the ominous reply was, “Nobody knows where he is.” American factory rider Nicky Hayden told a press conference that it was hard to keep his team’s morale up for the final race after his crew chief and half the staff were axed by higher-ups.

This may be the year of technological tour-de-force, as major teams pull out all the stops to combine smoothed acceleration with higher performance. Even if they reach parity in this, Rossi holds a deciding card: processing power. As Burgess said, “The brain inside the helmet is more use than all the technology in the world.”

While other riders’ brains signal, “I am sorry. All circuits are busy. Please place your call again later,” Valentino Rossi is watching, riding at 96 percent, making plans to pass at the very comer his opponent finds most difficult. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

February 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Fine Art of Planning To Crash

February 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCMaking It Easy

February 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

February 2005 -

Roundup

RoundupMoto Morini Lives!

February 2005 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupAmerica's Fertile Sportbike Ground

February 2005 By Mark Hoyer