WAR OF THE WORLDS

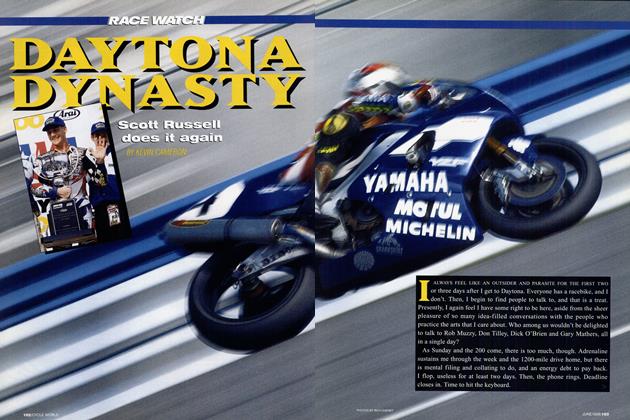

RACE WATCH

Where is Superbike racing headed, both here and abroad?

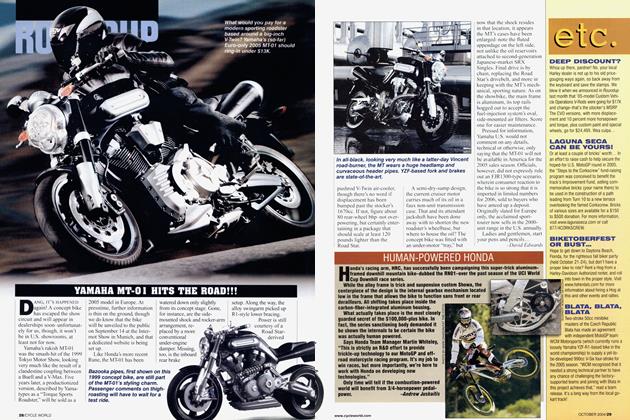

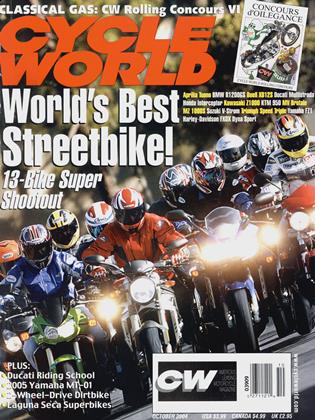

KEVIN CAMERON

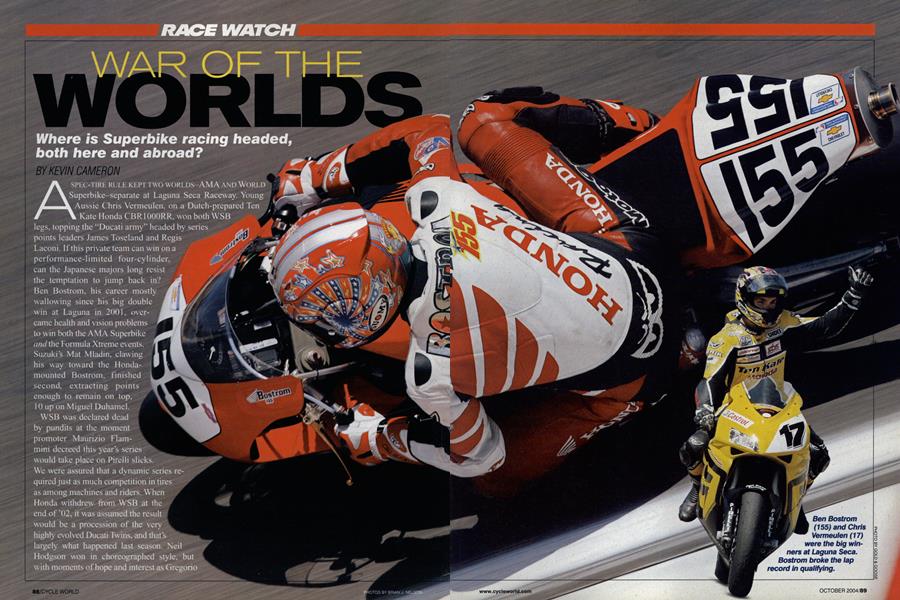

A SPEC-TIRE RULE KEPT TWO WORLDS-AMA AND WORLD Superbike-separate at Laguna Seca Raceway. Young Aussie Chris Vermeulen. on a Dutch-prepared Ten Kate Honda CBR1000RR. won both WSB legs topping the "Ducati army" headed by series points leaders James Toseland and Regis Laconi. If this private team can win on a performance-limited four-cylinder, can the Japanese majors long resist : the temptation to jump back in? Ben Bostrom. his career mostly wallowing since his big double win at Laguna in 2001, over came health and vision problems to win both the AMA Superbike and the Formula Xtreme events. Suzuki's Mat Miadin, clawing his way toward the Honda mounted Bostrom, finished second, extracting points enough to remain on top, 10 up on Miguel Duhamel.

WSB was declared dead by pundits at the moment promoter Niaurizio F lammini decreed this year~s series would take place on Pirelli slicks. \\~ were assured that a dynamic series re quired just as much competition in tires as among machines and riders. When Honda withdrew from WSR at the end of O2. it was assumed the result would be a procession of the very highly evolved Ducati Twins, and that's largely what happened last season. Neil llodgson won in choreographed style. hut with moments of hope and interest as Grcgorio Lavilla poked his Suzuki GSX-R1000 into the top five again and again. It was remarked at the time, “If someone of the caliber of Mladin were on that bike, the results might be quite different.” As an indication of Ducati s concern, its representatives assured all who would listen that, “The Suzuki is making 200 horsepower now, and next year...”

RACE WATCH CONTINUED

Let’s think about that. The Ducati 999R. based upon sustainable rpm and the cylinder filling achievable by a refined design, probably makes about 175 bhp. The lOOOcc Fours are limited to stock valve material and lift, and the Suzuki in particular has a longer stroke than the 999. Even with Ducati-levcl cylinder filling and the ability to equal with metal springs what Ducati does with desmodromic valve drive, the numbers yield no more power than for the Ducati. Further, the four-cylinder engine suffers loss from extra parts friction and

its greater hot-section surface area. This parity is in fact what we saw last year: Lavilla was able, on occasion, to ride his big Suzuki “in amongst ’em,” but never showed a speed advantage.

Now let's argue backward. This past spring at Daytona, one of the Honda CBRIOOORRS was speed-trapped at 194 mph, versus the more usual 185-mph numbers generated by the Suzukis. If the Suzuki actually makes that 200 bhp, Honda’s 194 mph would require 230 bhp. If that’s true, who needs MotoGP?

Now think about the recently discussed idea of adopting a spec tire in MotoGP as well. Until Bridgestone’s recent win by Honda’s Makoto Tamada in Brazil, any tire but Michelin’s “A” specials was a kiss of death-automatic condemnation to the bottom half of the finishing order. The fact that this has been true so long has detracted, not added, to the attraction of MotoGP. Why fund the

heavy cost of engine and chassis development, only to handicap yourself with tires that are at best a second slower? How did Bridgestone get Tamada on its brand? In the usual way: by a reported $9 million sponsor payment to Honda.

A spec tire brings all teams to closer parity in grip. I say “closer” because any spec tire may suit one brand or one rider’s style better than it does another. One thing it has certainly done is to confirm Carl Fogarty’s pre-season assertion that his three-cylinder Foggy Petronas machines would be a lot closer to competitive if all riders were on the same tire brand.

A less desirable result is a complete disconnect between World and AMA Superbike at Laguna. No American rider risked “tire excommunication” by riding the WSB event as a wildcard, so there could be no possible repeat of popular American wins such as those of Bostrom and Colin Edwards in recent years. Because of the current immaturity of the Pirelli slicks, not even distant comparison of US. vs. World riders was possible. Race lap times on the Pirellis were on the order of a second slower than in the AMA race. Bostrom set AMA pole at a lap-record 1:24.906, while Steve Martin topped WSB Superpole at 1:26.912.

Pirelli need not be embarrassed by this. Tires get faster every year. Should anyone be embarrassed that Michelins of a few seasons ago were 2 seconds slower than today, or that today’s tires are surely slower than next year’s? All tiremakers have the same knowledge and comparable engineers. This is proved by the fact that no company dominates street-tire performance. What separates a newcomer to racing from a veteran such as Michelin is the number of tests performed. Testing is expensive, but everyone in the industry knows how to do it. Bridgestone was received with derision when it entered GP racing, but it kept to its work and plowed through the

necessary testing. It was rewarded by Tamada's win-and by consternation on the faces of the Michelin crew, who must now redouble their efforts.

For a time, it seemed that V-Twins were “right” for WSB-so much so that Honda

and Suzuki built Twins of their own. Now lOOOcc Fours, with some power limitation, have been put among them. Aprilia withdrew to focus on MotoGP. Honda did much the same, giving the spec tire as its reason. Suddenly, Ducatis arc the only

RACE WATCH CONTINUED

Twins. Can they retain their glamour without the heat of `02-style competition to fascinate us? Or will Twins be revealed as a momentary artifact of a racing formu la that came and went?

The two WSB legs at Laguna were not boring, and Vermeulen was not the whole reason why. The rest of the action came from non-factory Ducati riders such as Martin, Noriyuki Haga and Pier-Francesco Chili, who pushed past the Ducati/Fila team bikes just as if this were a wideopen series rather than a factory benefit. Chili, who is a wonderful 40 years of age, came a popular second in race one. Martin, another veteran, took Superpole, and then scored a third and a sixth. Haga was himself, boldly taking his impossibly big lines, filling us with fear lest he explode into an off-track dust cloud at any moment. In Supcrpole, he did. He collected a sixth and a fourth. Ducati factory men Toseland and Laconi had to accept fourth and second, and fifth and third, respectively.

BRACE WATCH~ CONTINUED

And the three-cylinder Petronas challenge by riders Troy Corser and Chris Walker? The only finish by “Team Turquoise” was a 10th by Corser in race one-but after a creditable fifth in Superpole. The bikes handle and accelerate well and now have the power to lift their front wheels on the uphill run to the Corkscrew. Three DNFs are embarrassing. Airliner-like reliability is expensive. Small outfits lack the means to get answers as fast as they are needed, no matter how much we root for the undermutt.

What is Ten Kate? A better question is who? Gcrrit Ten Kate has operated his Dutch racing team with such professionalism that it was at the end of '02 reportedly under consideration to replace Team Castrol as Honda's official Superbike team. Do Vermeulen's bikes bristle with HRC pieces? Ray Plumb, cheerfully serving a life term as a team mechanic for American Honda, says he sees no trick pieces on the yellow bikes. Internal engine parts? Since we can't know, why speculate? The Ten Kate team knows how to make power.

TRACE WA? CII 1 CONTINUED

Although Ducatis are noted for generally loose setups, Vermeulen’s Honda was steady save for visible rear-wheel chatter during braking. It was interesting to watch at the Corkscrew during WSB Superpole, which presents one rider at a time, making a maximum effort. In general, the more a rider gassed it up and slid through the right at the bottom, the slower the lap time. Sliding is dramatic, but wastes energy that might find better uses.

Think about the stresses involved in revving production-based engines as high as AMA Fours are now turning. The Hondas, with a stroke midway between Yamaha’s short 53.5mm and Suzuki’s long-in-the-tooth 59.0mm, were revving to 13,000 rpm at Daytona, later raised to

13,500. What limits engine rpm is not piston speed-pistons and rings can slide a lot faster than they go now without running out of lubrication. The real limit is piston acceleration, directly proportional to stroke and increasing as the square of rpm. The harder the rod yanks the piston to a stop at TDC, the more tiny interior metallic bonds are broken in the wristpin bosses of the piston. These bond breakages accumulate in the metal until some of them become active, propagating cracks. This puts pistons on the critical parts-life list that every factory gives its teams. Run parts too long and they will fail. The lists are compiled by careful statistical work, based on the “spontaneous rapid disassembly events” that take place during factory testing. Changing parts at the life-list intervals is the key to a) finishing races and b) keeping failures private.

I like to imagine long, fluorescent-lit halls with dyno rooms located on either side. There is a smell of floor polish, fuel and hot oil. Parked, waiting for test-cell availability, are little metal carts, each carrying an engine with its documents and computer disk in an envelope. Tired technicians, longing for a smoke, talk > quietly as they wait for the 4 a.m. noodle man to come through. Heard through the soundproofing are the strangled sounds of engines on test, accelerating, upshifi ing, decelerating. driven by automated test cycles. Occasionally something hap-

pens, bringing techs on the run, and engi neers walking very quickly. This is where ideas become proven hardware. There is no problem grinding cams and winding valve springs for 13,500 revs in a 1000cc car engine-you just cx-

tend the valve timing to reduce the valve acceleration to something that steel springs can comfortably handle. Cars have huge tires, twice as many as bikes do, so when the light-switch power gen erated by long valve timing blinks on, they can handle it.

"~o~; you can see from the current Ducati Desmosedici MotoGP engine. When its power hits, the tire spins and the bike goes sideways. They first tried to fix this with altered weight distribution (the riders hated it), and are now experimenting with firing pairs of the four cylinders almost together rather than more equally spaced apart. This, because of non-linearities in the way rubber traction works, may give them some of the grip they need.

The common sense answer is to find a way to use shorter valve timing that gives power everywhere, with no traction-de stroying "hit." Short timing fills the cylin ders at lower revs because it forbids back pumping of fresh charge. Large valve area fills the cylinders at higher revs. The result is a smoother torque curve that a motorcycle’s single drive footprint can handle without spinning and sliding.

Trouble is, as you shorten the timing, valve acceleration has to increase because you are climbing the same hill but in a shorter time. Instead of a smooth push as the valve opens, it must receive more like a hammer blow. The valve springs, whacked in this way, don’t compress smoothly over their whole length. Instead, the rapid compression bunches the coils at the valve end of the spring, storing energy that later expands to travel up and down the spring as a vibration called “spring surge." Waves of stress bounce from end to end of the spring, greatly accelerating its fatigue and eventual breakage, and at unpredictable moments leaving the valve without enough force to control it.

Designers fight back by nesting two springs together snugly enough to act as friction dampers against each other. Or, accepting increased wire stress, they cut the number of coils, thereby raising the spring’s natural frequency high enough

to take it out of range of the engine's rpm. This calls for exceptionally fa tigue-resistant wire, made of trick vacu um-degassed steel, its surface ham mered into crack-delaying compression by controlled shot pecning. Lately, oval spring wire has been used to gain stiff ness, just as a 2x8 on edge is stiffer than

a 4x4. A current rage is the "beehive" spring, whose diameter shrinks as it ap proaches the valve stem tip. Not only does this make the moving end of the spring lighter, it also "confuses" the waves of spring surge because its natural frequency changes as it is compressed. Titanium valve springs also exist. They are advantageous because the material has outstanding fatigue properties and weighs only 60 percent as much as steel.

RACE WATCH CONTINUED

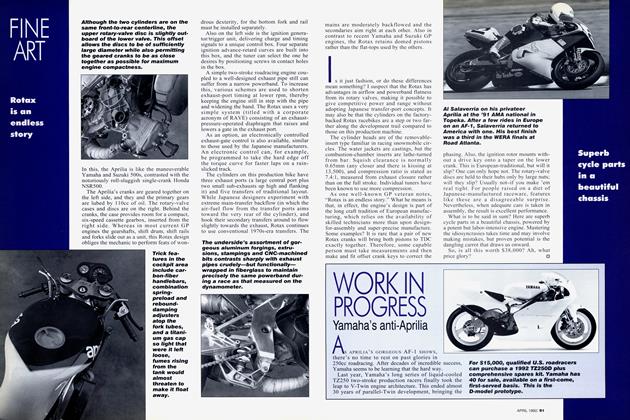

Reverberations of this work could be seen in an early Yamaha YZR-M1 on display in Laguna’s infield vendor’s row (where there were more stores, displays and buyers than ever before). The proportions of this engine’s cylinder head suggest it contains unusually short valves and Formula One-like lever cam followers-both measures designed to cut valvetrain weight drastically. This is done not in the name of ultra revs, but to make possible the shorter valve timing necessary to generate a wide, smooth torque curve. Effects of this kind of work are surely being felt in present and yet-to-come Superbike parts.

The various direction changes that have recently occurred in motorcycle racing have yet to be resolved but increased prosperity will help to lure Yamaha and Kawasaki back to both AMA and World Superbike. Yet the high cost of MotoGP threatens to suck away the funds to accomplish this. Which is the better use of the racing R&D dollar? Does the U.S. need both Superbike and its husky brother, Superstock? The latter is a temporary

parking lot that allows Yamaha and Kawasaki to keep their teams busy while higher management mulls over a return to Superbike. If Open-class Superbikes prove too fast for U.S. tracks (remember the tire problems Mladin had last season, and others had in pre-Daytona testing this year?), would manufacturers or spectators accept a “mini-Superbike” grown out of Formula Xtreme? Or answer this one: Will the world’s insurance carriers continue to nod and smile at 150-bhp streetbikes? If not, what next?

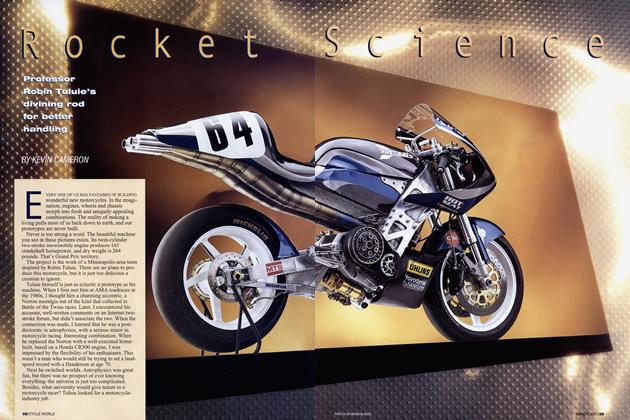

World Superbike has done racing a favor by forcing consideration of what a spec tire can do. Will WSB die in the attempt? No. The manufacturers want to sell production bikes, and WSB showcases them. Two years ago, I thought street-going replicas of MotoGP racers would come, giving rise after a year to even more blurring of the distinction between GP and Superbike. Ducati, in announcing its Desmosedici production bike, has moved in that direction. Who’ll be next? And then?

We humans make plans, but trial and error decide the outcome. There will be a few more jolts before racing settles into a new orthodoxy. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue