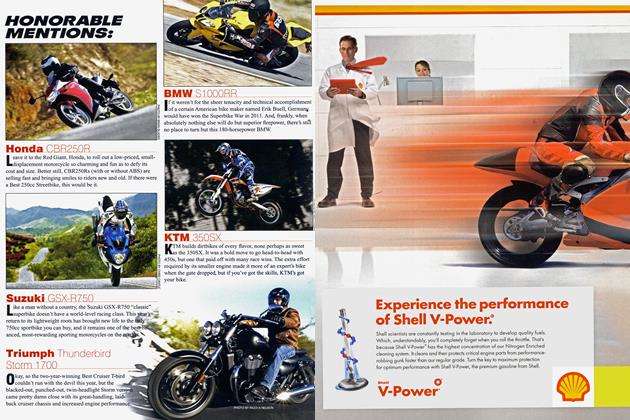

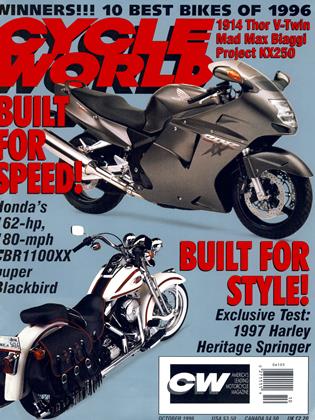

Super Blackbird

Honda's steamin' CBR1100XX debuts

KEVIN CAMERON

MACH 3.0 ON THE GROUND? THAT’S IMPLIED BY Honda’s choice of name for its new CBR1100XX: the Super Blackbird. The original Blackbird is Lockheed's 2100-mph SR-71 reconnaissance aircraft, the fabulous “Sled,” invulnerable to interception. For those of you who believe that speed and acceleration are truth, Honda has produced a new verity, a fresh definition of the Open-class sportbike. Here are the heavy new numbers: 162 crankshaft horsepower at 10,000 rpm; rumored top speed of 180 miles per hour.

Savor the numbers for a moment, then scan the concept. Everything Honda has revealed about this new machine suggests that it will not only make the numbers, but do so easily and in comfort. The 79 x 58mm, 1137cc engine is equipped with twin, second-order balance shafts to cancel the inlineFour’s natural high-frequency secondary vibration. Brakes are Honda’s Dual Combined System, similar to those on the STI 100. Rider position and wind protection are engineered for comfort. These design choices are more often thought of as luxuries of the sport-touring mission. How do they fit into the Blackbird’s obvious pavement-superiority sportbike role? Honda is telling us, by doing this, that it can push the envelope easily, redefining the sportbike as it goes, blending super-performance with refinement.

Changing demographics have summoned the Super Blackbird into being. Open-class bikes have carried insurance costs beyond the budgets of many riders. Recently, a new class of financially more capable motorcyclist has stepped into the showroom, gold card in hand, eager for ultimates. This buyer wants prestige of ownership, unmatched performance and luxury. For this rider, insurance cost is a secondary issue-not a deal-breaker.

Even if this bike’s claimed dry weight of 491 pounds grows the usual 10 percent in crossing the Pacific, this will be the lightest and most powerful of the 1 lOOcc Fours. It becomes the motorcycle equivalent of the most luxuriously appointed, super-performance sports cars such as the McLaren FI. This is a sportbike, with tremendous power and speed, chain drive, and brakes and chassis to match-yet able to provide maximum comfort. This ’Bird is for riders who want the most, without the suffering that too often accompanies it. There are no look-at-me, beach-pants graphics here. The Blackbird, with its conservative, single-color paint schemes, can speak softly because of the big stick that it is.

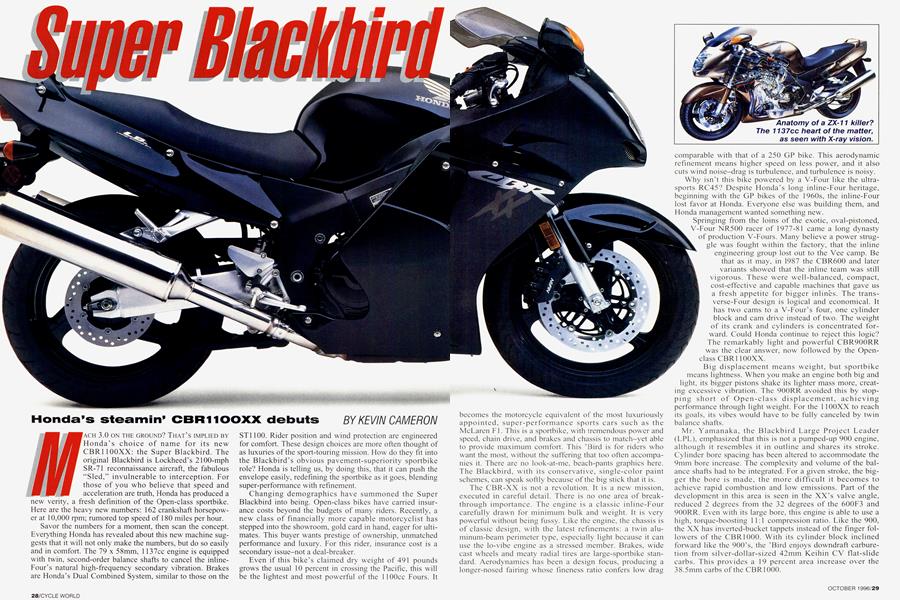

The CBR-XX is not a revolution. It is a new mission, executed in careful detail. There is no one area of breakthrough importance. The engine is a classic inline-Four carefully drawn for minimum bulk and weight. It is very powerful without being fussy. Like the engine, the chassis is of classic design, with the latest refinements: a twin aluminum-beam perimeter type, especially light because it can use the lo-vibe engine as a stressed member. Brakes, wide cast wheels and meaty radial tires are large-sportbike standard. Aerodynamics has been a design focus, producing a longer-nosed fairing whose fineness ratio confers low drag comparable with that of a 250 GP bike. This aerodynamic refinement means higher speed on less power, and it also cuts wind noise-drag is turbulence, and turbulence is noisy.

Why isn’t this bike powered by a V-Four like the ultrasports RC45? Despite Honda’s long inline-Four heritage, beginning with the GP bikes of the 1960s, the inline-Four lost favor at Honda. Everyone else was building them, and Honda management wanted something new.

Springing from the loins of the exotic, oval-pistoned, V-Four NR500 racer of 1977-81 came a long dynasty of production V-Fours. Many believe a power struggle was fought within the factory, that the inline engineering group lost out to the Vee camp. Be that as it may, in 1987 the CBR600 and later variants showed that the inline team was still vigorous. These were well-balanced, compact, cost-effective and capable machines that gave us a fresh appetite for bigger inlinës. The transverse-Four design is logical and economical. It has two cams to a V-Four’s four, one cylinder block and cam drive instead of two. The weight of its crank and cylinders is concentrated forward. Could Honda continue to reject this logic? The remarkably light and powerful CBR900RR was the clear answer, now followed by the Openclass CBRl 100XX.

Big displacement means weight, but sportbike means lightness. When you make an engine both big and light, its bigger pistons shake its lighter mass more, creating excessive vibration. The 900RR avoided this by stopping short of Open-class displacement, achieving performance through light weight. For the 1100XX to reach its goals, its vibes would have to be fully canceled by twin balance shafts.

Mr. Yamanaka, the Blackbird Large Project Leader (LPL), emphasized that this is not a pumped-up 900 engine, although it resembles it in outline and shares its stroke. Cylinder bore spacing has been altered to accommodate the 9mm bore increase. The complexity and volume of the balance shafts had to be integrated. For a given stroke, the bigger the bore is made, the more difficult it becomes to achieve rapid combustion and low emissions. Part of the development in this area is seen in the XX’s valve angle, reduced 2 degrees from the 32 degrees of the 600F3 and 900RR. Even with its large bore, this engine is able to use a high, torque-boosting 11:1 compression ratio. Like the 900, the XX has inverted-bucket tappets instead of the finger followers of the CBRl000. With its cylinder block inclined forward like the 900’s, the ’Bird enjoys downdraft carbure -tion from silver-dollar-sized 42mm Keihin CV flat-slide carbs. This provides a 19 percent area increase over the 38.5 mm carbs of the CBRl 000.

The 1 100XX's bore/stroke ratio is a modern-but-not-extreme 1.36, and the engine gives peak power at a reasonable 10,000 rpm. This translates to a sporting 3800-feet-per-minute piston speed. Piston speeds creep upward all the time, as materials and design improve. Thirty years ago, 4000 fpm was considered the limit for pure racing engines, but yesterday’s limit is today’s production standard.

Exhaust is via a 4-into-2-into-l-into-2 system. Twin mufflers are necessary to mute this engine’s large voice.

The claimed result is 162 horsepower at 10,000 revs, with peak torque of 91 foot-pounds at 7250 rpm. This is measured at the crankshaft, as engines are dynoed at the factory, not at the rear wheel as is standard magazine-test practice. What’s the difference? In the first case, power goes straight to the dyno without loss. In the second, it has to pass through the entire powertrain. Gears are maybe 98 percent efficient, so subtract 2 percent each for primary gears and transmission, then another 3 percent or so for the chain and sprockets, for a total of 7 percent loss. If our dyno is rearwheel-driven, another bite will be taken by the tire, for a total loss of some 15 percent. This adjusts the big number down to a range of 138 rearwheel horsepower-still a most impressive number. Keep these adjustments in mind when you read our coming Blackbird road test, to see why magazine test figures are always lower than manufacturers’ claimed power.

How hard is this engine working to make its power? The numbers say it chums out about the same stroke-averaged combustion pressure (BMEP) as Honda’s CBR900RR, which has a desirably chunkier powerband than the average highly tuned sportbike. Bigger BMEP numbers exist, but making them requires tuning that narrows power, requiring the rider to toe the gearbox tirelessly in search of the engine’s sweet spot. This isn’t appropriate to the Blackbird’s mission of civilized superi ority. To paraphrase the old boxing axiom, a good big engine will always beat a good little engine.

Now consider those whispered suggestions of 180-mph top speed. Reasonable? The power is there, and we know that bikes with less horsepower have been magazine-tested at as high as 176 mph. On Blackbird stock gearing, 10,000 rpm translates to a top speed of 170 mph, but in top-speed runs it's com mon for these big bikes to overrev to higher speed than their power peak rpm would suggest. They have so much power that they can continue to accelerate even as power falls slowly after peak. In one Kawasaki ZX-11 test, for example, the engine was overrevving by 1200 rpm at its all-out top speed. It will only require a 600-rpm overrev by the XX to reach the magic 180. Invulnerable to interception?

Small details show that the Blackbird team is watching what you are watching. They speak of the “open look” of the twin 310mm front discs. What is this? It is the way Superbike brakes look, now that mies require iron/steel discs to be used instead of super-light carbon. To emulate the lightness of carbon, engineers make the most effective use of metal to do the job. The resulting slim discs and carriers have that “open look.” Likewise, the O-ring drive chain on this machine is a lighter #530, having the same pitch used on 500cc GP bikes and Superbikes, rather than the ponderous #630 often seen. Details like lighter brakes, chains and sprockets add up.

Although this bike has a sealed airbox with its intake located in the highpressure region above/behind the front tire, the screened intakes you see are not ram-air ports. They exist to vent the oil cooler under the steering-head. These are details in the overall plan to manage airflow through and around this motorcycle. Because internal airflow generally causes more drag than the same flow over the exterior, air inlets for cooling and intake supply were downsized to real requirements. Front fender shape becomes part of the package here. To fit

into the narrowed nose section, the twin headlights were stacked vertically rather than placed side-by-side.

The Blackbird’s chassis, like that of the ’96 CBR900RR, has “engineered flexibility.” This provides supplemental suspension when the bike is leaned far over. At high cornering angles, the normal suspension is less able to absorb shock because it and the bumps are now acting in different directions. Making the chassis more limber can indeed absorb small bumps, making the bike stabler over rough corners, but this is a band-aid, not a longterm answer. The frame is a spring without a damper to moderate motion. Engineer Yamanaka answered this observation by stating, “We have many new technologies to deal with unwanted chassis motions in future.” When I asked for specifics, he replied, “Chassis oscillation energy can be changed into electricity or light.”

Strange, but true! This is the new field of “smart structures,” in which unwanted motion is detected and actively damped by use of embedded sensors, piezoelectric materials (substances that generate electric charge when deformed) and computers. Skis employing such technology are already on the market, and aircraft applications are under development. Clearly, Mr. Yamanaka has been studying.

The more engine you put into a chassis, the more “wheelie resistance” has to be built into it, in the form of longer wheelbase. The XX’s 58.7 inches are normal for so powerful a machine. Wheel travel on the Blackbird is 4.7 inches at each end. Front dampers are of the cartridge type, rear suspension is conventional linkage and single shock.

The ’Bird’s suspension, like that of the latest 900RR, employs Honda s so-called HMAS concepts (we are instructed to say “Aitch-mass”). Modem street and roadrace suspensions have developed from solutions devised for motocross. Engineer Baba (formerly LPL for the 900RR) came to believe that these solutions contained unexamined conclusions that needed critical review. With the big MX damper sizes necessary to absorb jump-landing energy, sensitive control of low-speed motions was more difficult. Bigger is not always better. By sizing damper pistons and valving to roadbikes’ real energy-absorption requirements (smaller), it was possible to refine lower-speed motions without causing either harshness or wallowing. Honda’s aim is to break the stereotype that harsh ride and good handling are brother and sister, to replace “or” technologies with “and” technologies. “Or” tells us we may have high performance or comfort, quick handling or stability, fun or durability. As more is learned and engineers’ understanding broadens, it becomes possible to put “and” in the place of “or.”

That is the Blackbird’s true mission.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue