Fixing things

TDC

Kevin Cameron

How DO WE LEARN TO DO THINGS? Many who later become motorcyclists grow up fixing things. A child confronts a wind-up alarm clock that doesn't go anymore. With a screwdriver it's possible to remove the case and reveal the works inside. Shaking the clock causes it to tick a few times, and demonstrates the back-and-forth rotation of the balance wheel. The clock is fully wound-why does it stop? Looking more closely reveals that the balance wheel doesn't move freely; it is a bit tight in its bearings. An even closer look shows that the balance shaft bearings are a pair of threaded cups, each supporting one end of the shaft. Therefore it should be possible to unscrew one of the cups just a bit. But wait. How did the shaft get tight in the first place? Did the clock get dropped, bending its frame? Did the bearings tighten from operation without oil? Soon one of the cups is unscrewed slightly and the balance wheel turns freely. How can the mechanic get oil into such a small place? With a needle! Poking the point of a needle into a drop of oil takes away a tiny amount, which can then be placed precisely where it's needed. The clock runs again.

This kind of story makes perfect sense to those who have lived it. For many others, however, the saga of child clock repair is a complete mystery.

“Who taught you how to do that?” they ask.

It is currently a severe problem for the armed services of the world to find people to whom technology makes sense. Instead of playing with broken clocks, children today are more often bent over their homework, preparing for a hopedfor white-collar career. Car dealers seek as mechanics those who have grown up in relative financial hardship, because such people have already had to learn how to keep their cars, washing machines and clocks running. As long ago as the 1930s, military forces were discovering that fewer people every year were capable of keeping a vehicle or other complex machine running. Why? Fewer recruits every year were coming from farms-the traditional hothouse of ingenuity-and more were coming from urban areas in which they were more likely to be office workers or clerks.

One attractive response to the need for technicians (and even engineers) is to train people in strict procedures of the “Insert tab A in slot C” variety. As long as the fasteners aren’t rusted solid and everything looks like the exercises in the training manual, this can work-sort of. I have met numbers of people trained in this way who are unable to carry on a conversation about their work because they literally don t know what they are doing! This kind of training is like learning a magic spell. There is no discoverable relationship between “Wing of bat, eye of newt’’ and the intended result of the spell. If any part of the practical problem differs from the training manual, the procedure fails.

People arc better than that. A friend had a job training service personnel to repair new-model Canon copiers. When he began his first class in the field, he was surprised to find that many of the people he was supposed to train knew much more about copiers than he did. In one case, the factory procedure required two hours and extensive disassembly, but one “trainee” showed him another, much quicker way to reach the damaged part.

Back in the 1960s, some Honda Hawk and Super Hawk Twins had gearbox problems. The formal repair procedure called for engine removal and complete disassembly, but flat-rate mechanics soon discovered that they could flip the machine upside-down, pull the bottom of the crankcase, and reach the problem, leaving the engine in the chassis and the cylinder and head in place.

A couple of years ago at Daytona I encountered a crusty retired Air Force mechanic who was full of such service stories. Because the military has the job of turning any human material into specialists, it tends to rely on proceduresbased training of the “Insert tab A” variety. But in this man’s unit, the commanding officer had for some reason decided to experiment with the idea that every person has a brain. They therefore went at their jobs not as strictly defined procedures, but as a way to get a certain result. That year, this particular unit went on to win about half of the Air Force’s special awards for all the improved tools and methods they developed in their work.

During WWII, a thousand B-29 bombers were deployed to islands in the Pacific. Assigned to each machine was a crew of 75 maintenance specialists-engine people, sheetmetal men, radar techs, etc. Maintenance proved to be a serious bottleneck. When General Curtis LeMay took command in 1945, he changed the system. Among 1000 engine mechanics, maybe 50 really knew what they were doing, 800 were only procedurestrained, and another 150 were next to useless. LeMay created separate departments, organized assembly-line style, with service jobs run by the people who knew what they were doing. The 50 top engine men analyzed problems and decided what needed doing. The 800 carried out the planned work, while the luckless 150 fetched parts and ran the engine hoists and tractors. Everybody learned something and service became faster and more effective. The percentage of aircraft available for missions rose significantly.

People are clever creatures, but today in our world of specialists we tend to think we need lessons in order to tackle such activities as riding a pony, resetting a circuit breaker or changing engine oil. This is unfortunate, because it gives people the idea that technology is magic, that there is nothing we nonwizards can discover or do about it. This puts a wall between people and things they could otherwise understand and therefore enjoy more. The wall takes some climbing, and the ascent is easiest begun in childhood, but it’s never too late to begin. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMy Brother's Beemer

October 2004 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsColorado Mountain High

October 2004 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

October 2004 -

Roundup

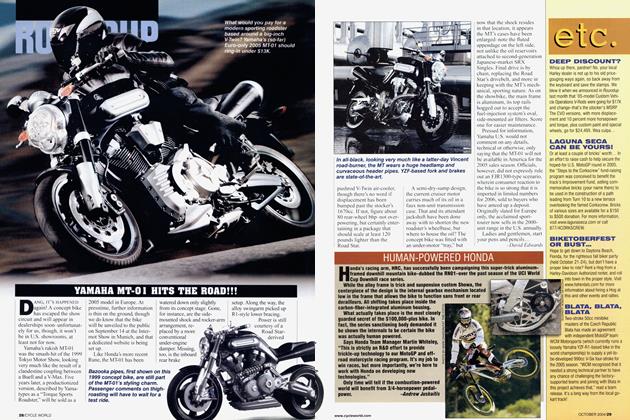

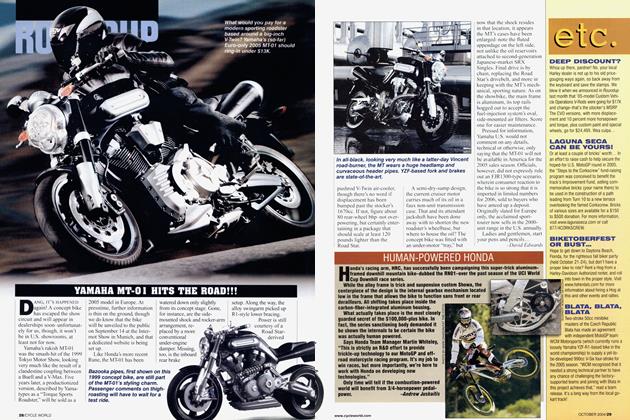

RoundupYamaha Mt-01 Hits the Road!!!

October 2004 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupEtc.

October 2004 -

Roundup

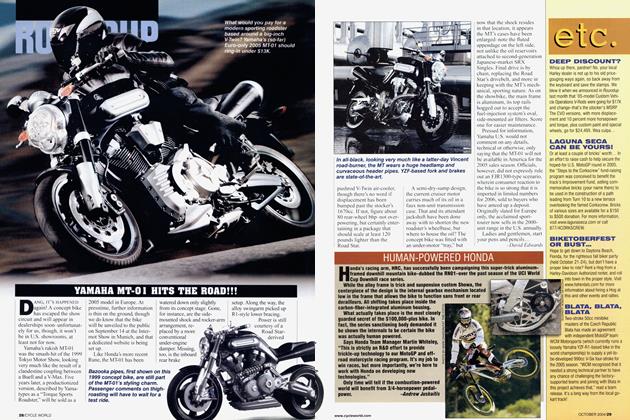

RoundupHuman-Powered Honda

October 2004 By Andrew Juskaitis