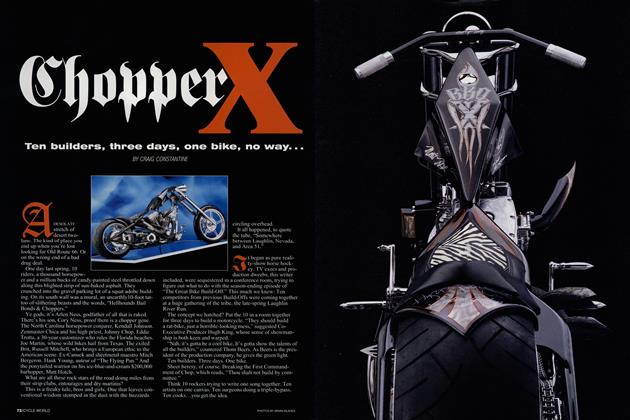

ROADOG REVEALED

Apologies to Dodge, but "Wild Bill" Gelbke put car engine to motorcycle more than 35 years ago

COME AWWWN. GET REAL. DON’T BS a BS’er and all that. Two Roadogs?

The impossible, larger-than-life motorcycle had a mate? The random pile of dissociated car parts had a clone? There was a Roadoppelganger?

But suppose it is true; what does it say about a barroom legend that bikers have largely taken as gospel? And what does it say about the veracity of a certain well-known nice guy and motorcycle authority? And gulp, glarg, what does it portend for a television special that includes the Roadog story in its now possibly bogus form, and of which I am producer?

New York, we have a problem. Did you really have no way of knowing that something like this was in the wind?

Only a vague uneasiness in the gut. Something about disturbing, but not reburying, a ghost-one capable of building, and riding, a 17-foot-long, 3280-pound motorcycle.

Or maybe even two.

I’m a rider (Harley FXR, Honda F4i) and producer (cable television documentaries). Naturally, my idea of professional heaven was doing a show about bikes. It happened that in mid-2002,

production began on a two-hour motorcycle episode for The History Channel’s long-running “Modem Marvels” series. The TV execs looked around the parking lot, saw a black Harley, and traced it to a guy with a permanent case of helmet-hair. And that’s how I got my dream gig.

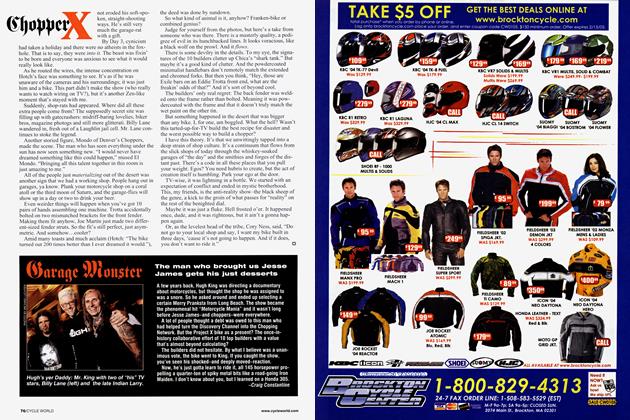

Which much of it was. Deconstructing ’60s choppers with Jesse James. Hanging for a morning with Mike Metzger as he stuck a series of perfect backflips. Interviewing the editors at my favorite bike mag. Jawboning with Jay Leno and then-on a sort of dare-riding the bechinned one around Burbank in his 1927 Harley-Davidson JD sidecar rig.

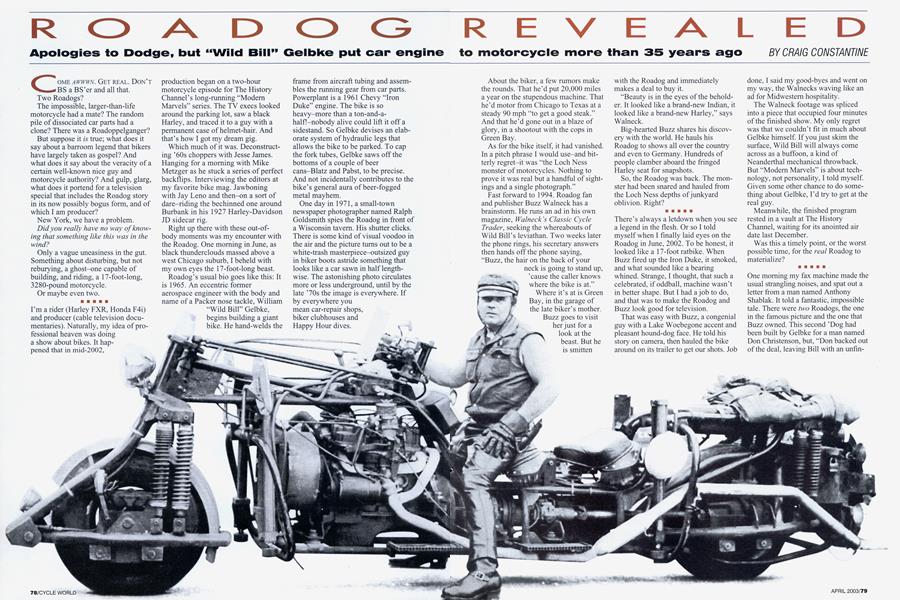

Right up there with these out-ofbody moments was my encounter with the Roadog. One morning in June, as black thunderclouds massed above a west Chicago suburb, I beheld with my own eyes the 17-foot-long beast.

Roadog’s usual bio goes like this: It is 1965. An eccentric former aerospace engineer with the body and name of a Packer nose tackle, William “Wild Bill” Gelbke, begins building a giant bike. He hand-welds the frame from aircraft tubing and assembles the mnning gear from car parts. Powerplant is a 1961 Chevy “Iron Duke” engine. The bike is so heavy-more than a ton-and-ahalfl-nobody alive could lift it off a sidestand. So Gelbke devises an elaborate system of hydraulic legs that allows the bike to be parked. To cap the fork tubes, Gelbke saws off the bottoms of a couple of beer cans-Blatz and Pabst, to be precise. And not incidentally contributes to the bike’s general aura of beer-fogged metal mayhem.

One day in 1971, a small-town newspaper photographer named Ralph Goldsmith spies the Roadog in front of a Wisconsin tavern. His shutter clicks. There is some kind of visual voodoo in the air and the picture turns out to be a white-trash masterpiece-outsized guy in biker boots astride something that looks like a car sawn in half lengthwise. The astonishing photo circulates more or less underground, until by the late ’70s the image is everywhere. If by everywhere you mean car-repair shops, biker clubhouses and Happy Hour dives.

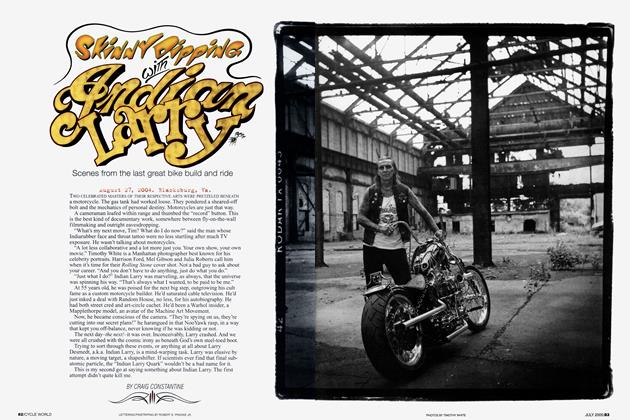

CRAIG CONSTANTINE

About the biker, a few rumors make the rounds. That he’d put 20,000 miles a year on the stupendous machine. That he’d motor from Chicago to Texas at a steady 90 mph “to get a good steak.” And that he’d gone out in a blaze of glory, in a shootout with the cops in Green Bay.

As for the bike itself, it had vanished. In a pitch phrase I would use-and bitterly regret-it was “the Loch Ness monster of motorcycles. Nothing to prove it was real but a handful of sightings and a single photograph.”

Fast forward to 1994. Roadog fan and publisher Buzz Walneck has a brainstorm. He runs an ad in his own magazine, Walneck ’s Classic Cycle Trader, seeking the whereabouts of Wild Bill’s leviathan. Two weeks later the phone rings, his secretary answers then hands off the phone saying,

“Buzz, the hair on the back of your

neck is going to stand up, ’cause the caller knows where the bike is at.” Where it’s at is Green Bay, in the garage of the late biker’s mother. Buzz goes to visit her just for a look at the beast. But he is smitten with the Roadog and immediately makes a deal to buy it.

“Beauty is in the eyes of the beholder. It looked like a brand-new Indian, it looked like a brand-new Harley,” says Walneck.

Big-hearted Buzz shares his discovery with the world. He hauls his Roadog to shows all over the country and even to Germany. Hundreds of people clamber aboard the fringed Harley seat for snapshots.

So, the Roadog was back. The monster had been snared and hauled from the Loch Ness depths of junkyard oblivion. Right?

There’s always a letdown when you see a legend in the flesh. Or so I told myself when I finally laid eyes on the Roadog in June, 2002. To be honest, it looked like a 17-foot ratbike. When Buzz fired up the Iron Duke, it smoked, and what sounded like a bearing whined. Strange, I thought, that such a celebrated, if oddball, machine wasn’t in better shape. But I had a job to do, and that was to make the Roadog and Buzz look good for television.

That was easy with Buzz, a congenial guy with a Lake Woebegone accent and pleasant hound-dog face. He told his story on camera, then hauled the bike around on its trailer to get our shots. Job done, I said my good-byes and went on my way, the Walnecks waving like an ad for Midwestern hospitality.

The Walneck footage was spliced into a piece that occupied four minutes of the finished show. My only regret was that we couldn’t fit in much about Gelbke himself. If you just skim the surface, Wild Bill will always come across as a buffoon, a kind of Neanderthal mechanical throwback. But “Modem Marvels” is about technology, not personality, I told myself. Given some other chance to do something about Gelbke, I’d try to get at the real guy.

Meanwhile, the finished program rested in a vault at The History Channel, waiting for its anointed air date last December.

Was this a timely point, or the worst possible time, for the real Roadog to materialize?

One morning my fax machine made the usual strangling noises, and spat out a letter from a man named Anthony Shablak. It told a fantastic, impossible tale. There were two Roadogs, the one in the famous picture and the one that Buzz owned. This second ’Dog had been built by Gelbke for a man named Don Christenson, but, “Don backed out of the deal, leaving Bill with an unfinished motorcycle,” claimed Shablak. Gelbke completed the bike but was not known to ride it much, if at all.

As for Buzz, “Walneck was fully aware that the motorcycle he had purchased was in fact not the original Roadog but merely a copy,” asserted Shablak. “I am indeed the owner of the original Roadog and have had it with the lies!”

In other words, seeming gibberish. The kind of bellyaching that periodically bubbles up in TV land. But naturally, I called Buzz to see if he knew this character Shablak. There was a noticeable catch in Walneck’s voice when I uttered the name.

Suddenly, here was a different guy on the other end of the line, a mumbling, dissembling man who was clearly very stressed. “Now, I never made any secret about that. I never advertised the fact that there were two bikes, but I never denied it,” he offered.

Kind of a spectacular omission,

Buzz, I thought. But what about the double ’Dogs? “There were two bikes, as I said, and I bought the one that was most complete. The other one was in parts and wasn’t for sale at the time.”

We had arrived at the moment of truth. “Buzz, in your opinion, is your bike the Roadog in the photograph?”

“I have reason to believe that it’s not,” came the sorry reply.

Two Roadogs?

’Tis true. Holy jumping Peter Jennings caught with his fly open on national TV, it’s true.

A number of awful scenarios simultaneously played out in my mind. Buzz gave voice to the worst of them. “This doesn’t mean that the story won’t get shown, will it?”

The next few days were spent making feverish preparations to get the show back and correct it. Then The History Channel yanked that portion of the story outright.

The right call, no doubt. Sound journalism and all that. Still, I hope that when the show aired, at the fateful edit point, somebody in the room with you loudly broke wind.

Thus the messy stillbirth of my Roadog video essay. But there is a consolation, and you are looking at it. For I finally get to tell you about Wild Bill Gelbke.

I tracked down Bill’s mother and Anthony Shablak by telephone shortly after my piece was canned. The William Gelbke they described was a long Brett Favre bomb away from the beery legend.

For starters, his stature. Gelbke was by no means the giant of myth. As Shablak said, “I’ve got all his leather jackets and I can’t get into them. I’m 6-foot-1. If he was 5-foot-5 he’s lucky, All the more amazing he could ride that motorcycle.”

Next, the Blatz-for-brains cliche. Gelbke was in fact an early electronics engineer, one of the Space Age bright boys. In the ’60s, he designed guidance systems, so-called “black boxes,” for Patriot missiles. But according to his mother, he quit, “Because they wouldn’t let him see plans for the entire missile. They ordered him to stick to the black boxes.”

Why own the Roadog? "I didn't buy that bike to show it and make money off it and sel! Tshirts and posters and all of that/' current caretaker Anthony Shablak says. "I bought that bike because I wanted to ride it." On the riding issue, though, he is now torn. "It's like a piece of folklore-what if I wrecked it?" Then there's the Insurance Man. "No insurance company in Wisconsin will touch it," he says.

His subsequent and to me supremely reasonable efforts to build a “heavyduty motorcycle that would last forever” have been chronicled elsewhere. Let’s get right to the troubling “blaze of glory” myth.

It is November, 1978. Gelbke is 43 years old. His unbreakable carengined motorcycles haven’t caught on, for now (but think Boss Hoss). He’s working on the design for a mass-produced hot-rod (think Plymouth Prowler). He has also pledged a kidney to his older sister, who is on dialysis.

Gelbke owns a tractor-trailer in which, when he needs money, he does a haul. Vegetables and such things, according to his mother. But the police think that it’s dope. They also know that he’s recently licensed a gun.

On the 17th, a dozen or more policemen approach the rented farmhouse outside of Green Bay where Gelbke lives. One of them, Jack Nagel, goes way back with Bill. In high school, it’s rumored, Gelbke had stolen Nagel’s girlfriend.

They call for Bill to throw out his weapon. There are two versions of what happened next. Nagel claimed that Bill fired, hitting him in the knee. Others say that Bill threw down his gun, but then the cop tripped on the ice. And his partners believed he’d been shot.

In any case, the police blazed away, hitting Gelbke several times. Nagel was taken by ambulance to the hospital. Cruelly, Wild Bill was left to bleed to death on the frozen earth.

With Gelbke’s death, his sick sister’s demise was now assured. Without the kidney donation, she died in February. With terrible swiftness, the Gelbke family was decimated (William Sr. had passed three years earlier).

There is a bizarre, only-inWisconsin postscript. Supposedly shot that morning, Officer Nagel made it to the Packer contest that afternoon. “I wouldn’t miss the game,” he told a TV reporter.

“I’m all talked out,” is all Mrs. Gelbke has to say today.

And now I finally know what troubles me when I see latter-day pictures of the Roadog, or when I eyeballed that other ’Dog in person. The bike seems incomplete because the biker is missing. That 17-foot motorcycle resulted in a famous photo and long-running legend, but the renegade engineer in the silly cap and scuffed leathers did the job, too.

The man who sees the real Roadog every time he opens his garage agrees. “I’ve taken hundreds of pictures of the bike,” says Shablak. “It never looks the same as the poster. Bill’s not there.”

With due respect to the popular “Modem Marvels” series, I no longer believe there’s any separating man and machine.