Skinny Dipping with Indian Larry

Scenes from the last great bike build and ride

august 27, 2004. Blacksburg, Va.

TWO CELEBRATED MASTERS OF THEIR RESPECTIVE ARTS WERE PRETZELED BENEATH a motorcycle. The gas tank had worked loose. They pondered a sheared-off bolt and the mechanics of personal destiny. Motorcycles are just that way.

A cameraman loafed within range and thumbed the “record” button. This is the best kind of documentary work, somewhere between fly-on-the-wall filmmaking and outright eavesdropping.

“What’s my next move, Tim? What do I do now?” said the man whose Indiarubber face and throat tattoo were no less startling after much TV exposure. He wasn’t talking about motorcycles.

“A lot less collaborative and a lot more just you. Your own show, your own movie.” Timothy White is a Manhattan photographer best known for his celebrity portraits. Harrison Ford, Mel Gibson and Julia Roberts call him when it’s time for their Rolling Stone cover shot. Not a bad guy to ask about your career. “And you don’t have to do anything, just do what you do.”

“Just what I do?” Indian Larry was marveling, as always, that the universe was spinning his way. “That’s always what I wanted, to be paid to be me.”

At 55 years old, he was poised for the next big step, outgrowing his cult fame as a custom motorcycle builder. He’d saturated cable television. He’d just inked a deal with Random House, no less, for his autobiography. He had both street cred and art-circle cachet. He’d been a Warhol insider, a Mapplethorpe model, an avatar of the Machine Art Movement.

Now, he became conscious of the camera. “They’re spying on us, they’re cutting into our secret plans!” he harangued in that NooYawk rasp, in a way that kept you off-balance, never knowing if he was kidding or not.

The next day—the nextl-ii was over. Inconceivably, Larry crashed. And we were all crushed with the cosmic irony as beneath God’s own steel-toed boot.

Trying to sort through these events, or anything at all about Larry Desmedí, a.k.a. Indian Larry, is a mind-warping task. Larry was elusive by nature, a moving target, a shapeshifter. If scientists ever find that final subatomic particle, the “Indian Larry Quark” wouldn’t be a bad name for it.

This is my second go at saying something about Indian Larry. The first attempt didn’t quite kill me.

CRAIG CONSTANTINE

August 2, 2004. Brooklyn, N.Y.

He walked into his shop like a hot spark into a combustion chamber. The energy around me surged and I found myself grinning while press ing the tattooed flesh of a remarkably self-pos sessed being.

I would come to see many Indian Larrys in the next few weeks, but this is the one everyone remembers. Garrulous, gregarious, boiling over with restless energy, manic, mercurial, talking about everything to everyone. He had that politician’s way of seeming to be endlessly generous with his time. You could be Joe Volkswagen and you’d come away flattered that you’d had the full attention of the great outlaw.

He was the anti-Jesse James. Jesse-to his great credit-fakes nothing and suffers no fools. He’ll charm your socks off when he’s in the mood, be on you like an attack dog when he’s not. Jesse’s on his own planet of cool, population one. Indian Larry’s planet was a crash-pad for the universe.

I was just another refugee who’d drifted into his shop. I was playing hooky from documentary television to direct episodes of something called “The Great Biker Build-Off.”

This hardly looked like work, at first. I’ve got the motorcycle jones, to the extent that I own two Harleys; and hanging out with the Indian Larrys of this world beat the hell out of interviewing guys in suits. I’d been at it for six months by the time I hit Brooklyn, though, and I was already restless. I missed the more “serious” fare.

Indian Larry had been on the “Build-Off” twice and had won both shows. The second time, famously, he rejected the winner’s trophy. He and his competitor, Billy Lane, cut the thing up with a blowtorch and threw the pieces to the crowd. It was a genuine gesture of solidarity that also happened to be an inspired piece of showmanship and self-promotion. And it was Indian Larry all over. Being himself rebounded ever more acclaim and credibility back to himself.

And so, he began his third “Build-Off,” against Mondo Pouras of Denver’s Choppers. We got the introductions out of the way and turned on the camera. I had an obvious question going in: “How do you top the last two bikes?”

He jumped on that softball and knocked it clean out of Brooklyn. He led us to a backroom where he was putting the final welds on an impossible motorcycle part-a frame made almost entirely out of limp chain.

“I always go for something mind-bending,” he said. “Here it is.”

The frame, of course, holds the whole works together-engine, transmission, wheels, etc. You want that sucker as stout as possible, which typically means big steel members. What Larry had done was take ordinary chain and weld each link to the next to create some stiffness. This was another bit of engineering anarchy. Normally you want as few welded-together pieces as possible, the joints being the weakest links. But Larry was going for the most welds.

There’d been talk since the ’60s of somebody, someday doing the all-chain frame. But until now, nobody had the cojones to follow through.

It wasn’t like Larry modeled and stress-tested it on a computer. He just started welding. “We think it’s okay. I don’t know, when I really drop the hammer on this bike, what’s going to happen, whether it’s going to buckle or snap. Honestly, personally, I have a gut feeling that it’s going to be fine.”

We would give that frame every chance to crumple into recidivist chain, on an 800-mile ride across the Alleghenies and Appalachia.

August 6, 2004. Brooklyn

This was the moon of misery, the back alley of the calendar, where the losers who don’t have a ticket out of town are left to stew in sweat.

Yet Larry wouldn’t have air conditioning in his workshop-on principle. “I like feeling the extremes,” he said to the melting TV director. “Why take the edge off reality, why anaesthetize yourself to life? I want to feel the heat in the summer, the cold in the winter.”

No heat on the Brooklyn waterfront in the winter? “Oh, we don’t want the pipes to freeze. I’ll turn the heat up to 45 degrees.”

He was a member of the Polar Bear Club, which swims at Coney Island every Sunday during the winter. On the club’s website is a picture of Larry, bare-chested in the surf, holding a big crust of snow.

He was fixated on pain. Pain as a portal to experience, pain as the background radiation of life, as something to be savored, harnessed. He had resolutely gone through life the outlaw way, the hard way, where nothing comes without suffering for it.

One day Larry let me read the treatment for his autobiography. The guy had an unbelievable life, a biker melodrama. He’d been born Larry Desmedí in a blue-collar Hudson River Valley town in 1949. One of his sisters had been murdered. Larry himself had taken a bullet to the head and barely survived. He’d done a stretch for bank robbery-he’d been the safecracker.

While no hippie, he crashed the big counterculture parties. He went to Woodstock and wound up in a famous Life magazine photo, atop a human pyramid. He’d lived in Haight-Ashbury, rolling longhairs for drug money.

He was a heroin junkie, and did whatever it took to feed his habit, including, sadly, stealing motorcycles. The junk did its level best to kill him. There was a period when he was, as Larry told me, “Homeless, shirtless, penniless. When you get to the absolute bottom there’s nowhere to go but up or die.”

He thought about suicide, but it wasn’t in him. In part because it was the easy way out-Larry didn’t do things the easy way. The tough guy pitted himself against the dark horsemen, heroin and booze. It took years of battling to get clean.

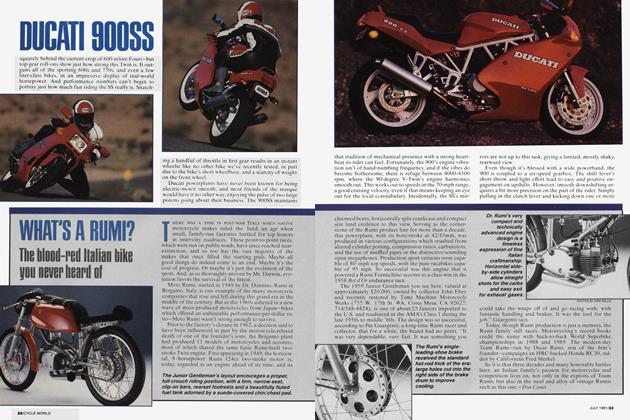

At the same time, the custom-bike crowd began talking about him. He always had a chopper, and it was often, he said, “the fastest bike in New York” when that meant street racing, through traffic, 100 mph on the Rockefeller. Now he began entering his hardcore machines against the artificial confections of the show circuit, and it wasn’t even fair. Larry’s bikes just stomped the field.

“There are plenty of bikes out there, custom bikes, that are subtle and sleek and beautifully constructed-they look like Bugattis-but that doesn’t have the impact,” he said. “You need to have the impact of an atomic bomb; people look at a bike and they’re just blown away by the details, the overall concept of it.”

He rode a chopped Indian Chief for a time.

Somebody called him Indian Larry and the name just fit-the craggy face, the silvering hair, sometimes braided into a warrior’s pigtails.

The universe was now spinning in Larry’s direction. Harley-Davidson had gone mainstream. So-called “reality” TV made its inroads. Discovery Channel discovered Jesse James. In the second Jesse James documentary, Larry was just one of the riders in the pack, but he stole a scene or two. And he was right there for the next big wave-“Motorcycle Mania” begat “Biker Build-Off,” and Larry became one of the breakout stars.

All of this may well have been serendipity and lucking-out, the idiot babble of events. But Indian Larry saw it differently. When he ran away from pain, deadened it with heroin and alcohol, the universe was an implacable enemy. Once he faced up to it, the manna just flowed. The TV shows, the book deal, fame. He had put himself into a state of grace.

August 11, 2004. Brooklyn

The portraits by White, Mapplethorpe and others have a monumental quality. The face seems cast in iron. It is defiant, unvanquished. A face that has aged, not been made old.

Such are the images that will make the Indian Larry myth, but that wasn’t really Larry. He didn’t go around fixing the world with that baleful existential glare. More often a knowing smile that seemed to say, “Look at us and what we’re getting away with,” played around those features. He wasn’t the Wise Elder, he was Coyote, the Trickster God.

The other thing was, he never stopped talking. I don’t know how photographers got him to be quiet for the time it took for their shutters to close. I tried. I’d say, “Larry, don’t say anything. Just stand there looking at the bike, and the camera will move around you.” For a second he’d stand, not still, but sort of hovering, the human hummingbird, in intense motion even when not moving. Then his mind would wander and his head would swing around, lit up with a new idea and looking for someone, anyone, to share it with. Before our camera was turned on, the lips were flapping again.

He was both a first-rate interview subject and a maddening one. He’d seldom answer a question directly. He’d Coltrane it, use it as a jumping-off point for fevered improvisation. I asked him how

the show’s 10-day deadline affected his creative process. He said, “There is no time. Time doesn’t exist. There is only the moment, this one right now.” And anyhow, the bike was completed in his mind long before the TV crew showed up: “I have projects looming in my head, I probably have five or six bikes in reserve right now that I’m going to start after I finish what I got going on. It’s almost like a curse. It’s an insane obsession.”

He’d talk ceaselessly about philosophy-the real kind, how best to live. “I’ve studied lots of different philosophies and metaphysics and theologies, everything from yogis to Bruce Lee,” he said. “And what works best for me is just roll with the mystery. Just let it unfold and try to be happy.”

His mantra was StaylnTheMoment. This was not the insipid pop mysticism of “Be Here Now,” it was the street version, something hard fought for, paid for in pain. But once attained, it was the fountainhead of infinite well-being and prosperity.

Spending all this time with the Zen Clown of Brooklyn, was, in my case, life-altering.

I’d seen the in-the-moment creed co-opted by hippies, self-help hucksters and basketball coaches. It seemed as bankrupt as “Just Say No.” But Larry was putting it to everyday use like a power tool and worldview combined. Larry made me a believer.

We also, occasionally, irritated the hell out of each other. As the TV guy, it was my job to ask prosaic questions about motorcycle components. What are apehangers? Velocity stacks? The questions annoyed Larry, and his wise-ass way of dodging them chafed me. We bickered and eventually full-on battled over it.

August 25, 2004. Elkins, W.Va.

The bikes were finally on the road, going fast through nowhere, a lost, spumed, half-remembered America that aches us as does a severed limb.

We’d selected West Virginia for the ride because it was unknown to us, the big question mark. I personally scouted the route, a series of two-lane highways that followed the river valleys of the Allegheny Mountains. The longest stretch was on U.S. Highway 219. North to south, it passes through horse country, a blip of an upscale ski area, immaculate dairy farms and, finally, the telegenic wrecks of Appalachian homesteads.

Into this hidden, sylvan nook of America came the “Build-Off” competitors and their entourage. A more incongruous biker gang never rode. There were well-heeled customers, including photographer White on his Indian Larry-built chopper, and hardcore bikers, among them Hell’s Angels. The pack was led by the camera crew in a pickup truck and van. A couple of semi-trailers, their drivers cursing their way through the hairpin turns, brought up the rear.

All these boys did not share my quaint notion of a West Virginia backroad as a righteous “run.” They expected action on their rides: biker bars, VIP lounges, free feeds at promotion-savvy Harley-Davidson dealerships, Hooters...

On old U.S. 219, there are no Hooters. Instead, there was the town of Elkins, our destination for the first night. The people we ran into at gas stops-where Indian Larry was always recognized and often mobbed-couldn’t hide their disbelief. “Elkins?!” scoffed one guy. “There’s nothing there. NOTHING. What you guys want to do is hit the Interstate, find a strip club, not go to freakin’ Elkins!”

I wanted to punch the guy out, but he’d given words to my own growing self-doubt. Had I willfully and stupendously miscalculated? Didn’t I know that Kerouac doesn’t cut it in a Doobie Brothers crowd? That there’s not enough doe-eyed country in the universe to pacify a biker who feels snookered out of a lap dance?

It was a surly, mutinous pack that pulled into Elkins around 6 o’clock. The night’s accommodations did nothing to elevate the mood. The motel was strictly no-frills, one of those oldfashioned jobs where the rooms opened onto the parking lot.

So much for the VIP treatment. So much for my own plans for the night, which had been to hole up with a book and a bottle of wine.

It was getting dark. I grabbed a beer and walked out into the parking lot, where some of the riders had gathered. A stack of pizzas arrived. The vibe somehow shifted. Suddenly was good to be there, just sitting on the pavement as the piney shadows closed in. We had earned this piece of a West Virginia parking lot. We were going to honor it.

More riders showed up, unfamiliar ones. Locals. Word had gotten around that the “Build-Off,” and Indian Larry himself, had rolled into town. People began gravitating to the bar next door. It looked like nothing special, just a beat-up country roadhouse. I had another beer and walked over-straight into an amazing scene.

The joint was full. It was rocking. The place looked like a million-dollar beer commercial. Big biker dudes strutted around with-and here was the thing-spectacular women in black leather. They would turn heads in L.A. or wherever, but here we were in Elkins, West Virginia. And they were gaping at Indian Larry. They were just mesmerized by this

being who had teleported straight from the Discovery Channel to their local dive. I saw one girl drift forward toward Larry as if against her will, as if he was levitating her.

I’ve been around a star or two, but I’ve never seen the 200-proof charisma, the intoxicating power of celebrity, that Larry had that night.

The main thing is, we went to a town where there was, as the man warned, NOTHING, and the action just burbled up around us. I for one rediscovered that night in Elkins what a motorcycle run is all about. You re the destination, even as you ramble from place to place. You don’t need to go to the party, the party comes to you.

Larry wasn’t surprised. When you stayed In The Moment, receptive to the incalculable unraveling of the eternal mystery, bitchin’ stuff happened all the time.

The previous afternoon, for example...

We were in a town that history briefly visited and then jilted forever, when Larry said, “I want to go swimming.”

Philippi, West Virginia, was the site of the Civil War’s first pitched battle, Federáis and Rebels fighting for control of a covered bridge across the Tygart River. It was beneath this civic pride and joy that Indian Larry felt like skinny-dipping.

It was the middle of the afternoon. People were driving back and forth on their errands.

A city park adjoined the river, where a guy and his young daughter walked their dog. We’d seen three police cruisers cross the bridge and then slow down as they double-taked the bikers.

None of this registered on Larry. He was hot, and there was cool water, so he stripped down and waded in. He was just In The Moment.

“Who’s going swimming with me?” he teased in that voice full of iron filings.

Suicide Jack and Big Joe from Vegas peeled off their clothes and followed him in. I turned it over in my mind for a minute. Then I did something I’ve never done or even contemplated. I stripped naked in front of a couple of dozen people and several co-workers, in broad daylight, and skinnied in.

This was “so wrong, for so many reasons,” as Dean the cameraman put it. The river was only a foot and a half deep, sluggish and scummy. And each skinny-dipper was on the wrong side of 50. Everybody else kicked at the riverbank and looked uncomfortable, thinking, “This is somehow gay. Or anyway unbikerly.”

I didn’t give a damn. The water was relatively refreshing and cleansing, at least scumming off the sweat. I was so far beyond being selfconscious that I wasn’t anymore. I was right there, in the here-and-now, Beyond Good and Evil, naked in the billion suns of The Moment. Indian Larry’s world.

After five minutes of splashing around in the Tygart, we pulled on our clothes and beat on down the road, into a future of pain.

August 28, 2004. Charlotte, N.C.

I was in the truck one last time, leading Indian Larry and the other riders through the streets of Charlotte. They were in high spirits, which meant messing with the “citizens.” They bumped their tires against our rear bumper at stoplights. Larry did his stand-up trick. It’s also called “surfing” the motorcycle. You just stand on the seat with your arms outstretched like a tightrope walker, crucified in the wind.

It’s a spectacularlooking stunt, but not a particularly difficult one. It’s a measure of Larry’s skill that he did it casually, in traffic and at high speeds.

Once we gained entrance to the bike show, I was flush with a sense of relief.

“At least we got them here safely,” I said to myself. Those exact words. The capricious hazards of the highway were behind us. This part was routine. The bike guys would do their star turns, posing with fans and signing autographs, while we followed with cameras.

Larry had this on-again, off-again agreement to perform stunts at the show. There were the usual hassles with the promoters-a contract had not been executed or payment had not been made, one of the two.

Why he performed that day isn’t clear.

Maybe he didn’t want to disappoint the fans.

Or maybe it happened because he was always pushing, promoting himself, overbuilding his career like one of his bikes. More likely, he was just in the mood.

Eight thousand people by some reports crowded four and five deep around a small racetrack. Larry warmed up by doing several stand-up passes. Then he pulled on a crash suit and a full-face helmet for a trick he’d done on Letterman. A 50-foot tunnel made out of cardboard was set afire. Dragging a guy on a rope, Larry gunned a sportbike through the fire. As he cleared the flames, a cannon fired.

It was the finale, the kicker to the show.

Another rider would have taken his bows and then found the beer tent. But Larry peeled off his suit and helmet and went back out on the track.

I once broached the subject of helmets. The answer was typical Indian Larry, which is to say original and combative. “Because that’s how I got famous,” he had said. “People see that it’s Indian Larry. They see my hair, my face. If I put on a helmet I’m just another anonymous stunt rider.”

His hair was streaming free, his stony face in the wind. He was doing the stand-up again. But he looked unsteady. Of all things, he seemed to be going too slow. The bike began to wobble.

In an expert move, Larry hopped from the seat to the footpegs, reaching for the handlebar. At the same moment, however, the front wheel

flopped in, halting the bike. It collapsed on its left side, pitching the rider to the right. All still would be right if the fall had been broken with his hands or shoulders, any body part but one. He did a half-pirouette in the air, though, and came down on the back of his head.

For hours, all was chaos and contradiction.

Rumors flashed through the crowd, proliferated on cell phones and modems, as in a natural disaster, an assassination. Fans from Manhattan to Tokyo learned he’d been airlifted to a hospital. He was reported to be unconscious but stable. Later we heard that he was fine, that the doctors just wanted to keep him overnight for observation. It was said that, being Indian Larry, he’d break out of the hospital and be back at the bike show that very day.

Then came another apparent rumor, because it was too cruel to be true, that he would not last the night.

August 30, 2004, Charlotte.

Indian Larry died at 3:30 in the morning. The cause was cerebral edema. And a precisely weird twist in a low-speed accident for a superfluous stunt. And an aversion to helmets that he attributed, unpersuasively, to creating his celebrity. And of being a hardcase in general. Hell, there ain’t no “cause,” just the universe living in its own Moment, the great tranny of Time, spinning a trillion or so rpm as it transmits the energy of all things from the uncreated to the unknowable.

Indian Larry’s body was cremated. His ashes were interred in the cylinder head of an old Harley Panhead motor that his pal C. J. Allan had engraved all over with Larry’s trademark “question-cross” logo. It’s the most kick-ass urn in history.

September 1, 2004. L.A., Calif.

The horror of it, the exquisite agony, was that he was very much alive on the videotape. There he is, the super-caffeinated hummingbird, darting from tool to tool, flipping wrenches as fast as the eye can track. There he is, the motormouth guru, forever yakking, bursts of blinding insight shooting through the verbal overload.

Everyone involved had their burden, their own private hell after Larry’s death. This was mine. I saw him alive every day and most waking hours. I had to replay scenes over and over again in order to transcribe his every word. I could neither forget how savagely alive he had been nor that he was now dead.

The pain. The guilt. What’s called survivor’s guilt, I suppose, and something else besides. I couldn’t shake the feeling that it wasn’t supposed to be this way. He should have gone on to his own show, the big networks, feature films. Larry would have been the first to say that there are no should-haves, that life gleefully reneges on promises. But it gave me not a moment away from the pain to think so.

All day the images of Larry repeated endlessly across my TV monitor, his words crawling across my computer like exotic, venomous insects.

At night I dived into a bottle of wine to escape the images. I’d wake up at 3 a.m. with the horrors.

The faces of Larry and his loved ones shimmered palely in the darkness. In my paranoia, they were condemning faces. They couldn’t accept that I’d been the last one with a camera. They screamed at me to not screw up, to do right by Larry.

Deadlines did their sinister walk-up, like the cop with the ticket book. The TV show somehow got done, and I’m told it turned out all right. Usually I am joyful at the little programs I put together. But there wasn’t an ounce of joy in this.

I’d wanted to do something “serious” again. Idiot...

September 19, 2004. Brooklyn

I had only walked this way once before, with Indian Larry, from the Bedford Avenue subway stop to his shop. He yakked all the while about the biker movie he wanted to make. I was listening and not paying attention to where we were going.

Now alone, I tried to find the numbered streets to North 14th, but I crossed a boulevard and lost the sequence. I’d made a wrong turn. No matter. I heard the massed motorcycle engines in the distance. I just homed in on the thunder, and found my way easily. A kind of navigation that Indian Larry would have approved.

I’d flown from L.A. to New York for Larry’s memorial. There was a Discovery Channel crew there, but I wasn’t part of it. I didn’t want to be there with a camera, doing interviews and the like. But why I had come, I didn’t really know. To pay my respects, of course, but there was some other reason. I couldn’t put my finger on it.

It was a brilliant fall day. The tag end of a hurricane had hammered New York two days earlier. In its wake, it had left this scrubbed, becalmed, somehow artificially serene city. It’s almost never this nice in New York.

I crossed through a police checkpoint and into a sea of bikers. There was a lot of anxiety about this gathering. Nobody knew how many thousands would descend on the anonymous -industrial block. People feared a riot, or rather some unfathomable Indian Larry-like Zen Clown anarchy.

But like the weather, the crowd seemed subdued. Another kind of hurricane had blown through, and everyone seemed chastened.

I walked through the multitudes to the familiar shop doorway overhung by the big question-cross. There was now a barricade barring the entrance. “Family only,” said a biker I didn’t know. I was once again a stranger in this place. I turned to blend into the crowd, when I heard my name called.

It was Timothy White. We hugged and caught up. He said something to the security guard and we were waved into the shop. Amid a shrine of candles and those famous black-and-white studies of Larry was the Panhead urn. And there was all of Larry’s extended family-his mother and sister, his wife Bambi, his seat-maker Paul Cox, his welder Eddie McCary, paint supplier John Riccolo, top-end motor builder Crazy Horse, Teddy Bear the journalist, Little John the tattoo artist, C. J. the engraver. There were members of clubs from the Hell’s Angels to the Polar Bears.

And now I knew why I was there. I had done an Indian Larry, acted out, as it were, a proof of his philosophy. I had faced up to Pain, and I had gone where the Moment led me. And the manna, the cosmic balm, had flowed. I hadn’t gone to Brooklyn to feel better, but now I felt immeasurably so. I was back in a state of grace.

There was beer and barbecue, a rockabilly band, a trophy presentation-Indian Larry’s shop had won its third “Build-Off” episode “All that’s missing is Larry,” people said, over and over. What you always say at a wake. But it was true. The spark wasn’t there to ignite the crowd, to shock it out of its hangdog mood.

I spent three hours on 14th Street and slipped away. I walked back to Bedford Avenue a different person. Still, I thought, all that’s missing is Larry. I said it aloud. “You’re somewhere, Larry, where are you?”

I swear this next part is true. When I reached Bedford, I sat down on the sidewalk, my back to a brick wall. A pigeon bobbed up. It reminded me of Larry, the manic, gawky motion. I said, “Larry? Is that you, Larry?”

That same moment something splashed on my head from the rooftop above. I took off my hat and looked at it. A thick blot of white. Pigeon shit.

Whether a message from beyond, or the universe copping a riff, it was pure Indian Larry. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

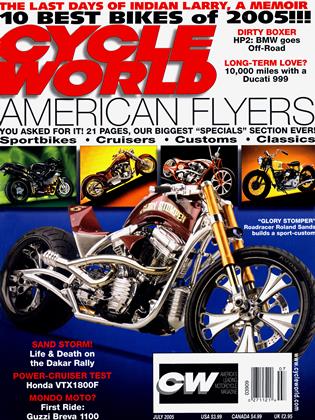

Up FrontGeneration Ten Best

July 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsInfamous Drawer of Useless Dead Weight

July 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCDuty Cycle

July 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

July 2005 -

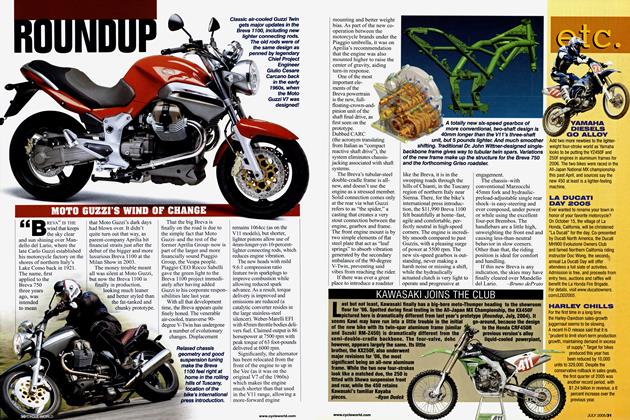

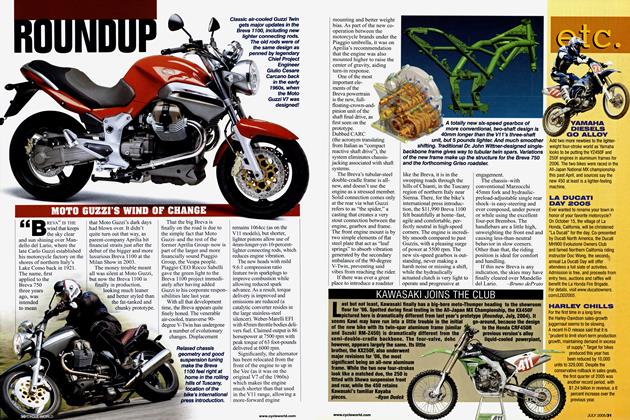

Roundup

RoundupMoto Guzzi's Wind of Change

July 2005 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

RoundupKawasaki Joins the Club

July 2005 By Ryan Dudek