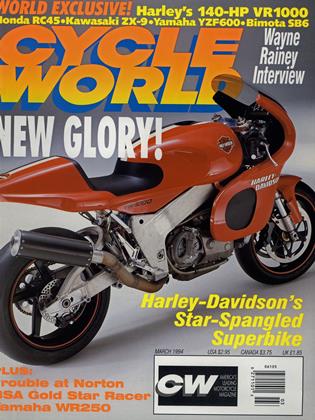

IT'S A GRAND OLD (BLACK AND ORANGE) FLAG

THE MOTOR COMPANY'S ROADRACING HERITAGE IS OLDER THAN RACING

ALLAN GIRDLER

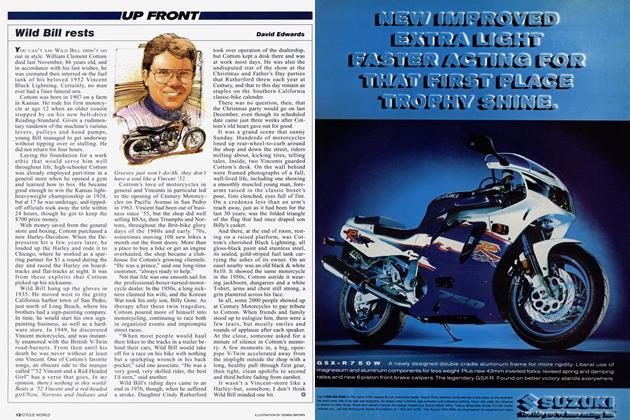

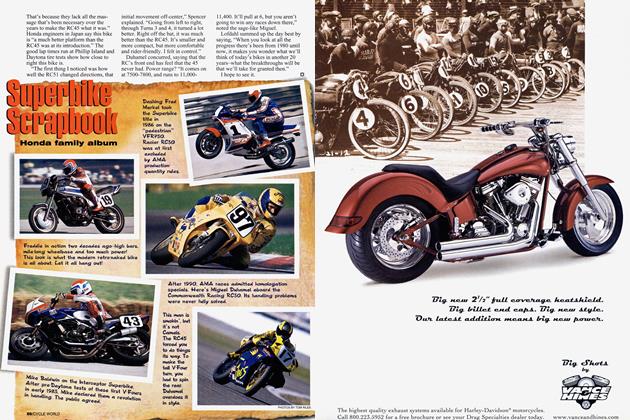

THINK BACK TO ANY ERA AND PICK a moment: Brad Andres, gunfighter eyes and gritted teeth, wrestling his bare-bones KRTT to victory on the tiny asphalt-and-gravel maze that was the Laconia National in 1958. The factory team four abreast across the line on the first lap of Daytona 1968. Cal Rayborn, “power sliding, man handling, crawling all over the bike, working the infield like no man alive,” as Cycle magazine reported that year, gaining on the corners only to have his underpowered and overheating iron XRTT lose it on the straights. An incandescent Jay Springsteen at Daytona in 1983, giving the Ducati teams lessons in courage and control as he wins the Battle of the Twins.

Oh yes. It’s been a while, but even so, Harley-Davidson’s astonishing and long-awaited VR roadracer is part of a long tradition.

If we wanted to stretch the point, Harley-Davidson was winning roadraces before there was such a thing, or even before there were that many roads.

Back in 1908, the Walter Davidson, one of the four founders and by all accounts a naturally gifted rider, entered a production H-D Single in an endurance run. He didn’t just win, he finished with a perfect score, so while it wasn’t strictly speaking a race, speeds were high enough to prove that only the Harley could keep the pace. That may be one of the reasons none of the other 21 makes in that event are still around.

But modern nostalgia, so to speak, doesn’t properly begin until we have closed-circuit races, on machines bearing a fair resemblance to what we ride to, as well as on, the tracks. The mid1950s, say. That’s when the American Motorcyclist Association established the Grand National Championship. They called it grand because points were awarded in mile, half-mile, shorttrack and TT dirt events, and in roadraces, never mind that back then the track could be part pavement and part gravel or sand, witness Laconia and Daytona Beach.

The controlling factor, and the reason 1954 was like now, is that the machines were supposed to be production bikes. The factory couldn’t just supply its own team, but had to make a set number, prove they’d done it, and offer exact versions for sale.

Nobody did it better than HarleyDavidson. The road machine was the K, a 750cc sidevalve V-Twin (what else?), so the racer was the KR, same size and configuration but lighter and stressed to the limit. That was just the beginning. The basic model was a dirtbike, no brakes or rear suspension, with tiny tank and high handlebar. The roadracer, called KRTT, used the same basic frame and engine but had a swingarm and shocks in the rear, plus generous drum brakes, a choice of big or really big fuel and oil tanks, and a choice of gearing-enough to fill pages of the detailed catalog.

So first, while the top teams naturally had a shop filled with bikes prepared for either miles or roadracing or whatever, the little guy could 1) walk into any Harley store and order any part in the book, and 2) take his one engine and frame and run it on the mile this week, the half-mile the next week and a road course the week after that. Thus Andres could win Daytona three times, as well as Laconia and the Langhom Mile and the Peoria TT, on the same basic bike.

Then the competition raised the stakes. During this particular Golden Age of Racing (a new one comes along every couple of years, thank goodness) there were several factories in contention. The British had good designs and their American teams had as much talent and determination as did Harley. Roadracing evolved. Harley’s KRTT went from dirt-track bike with brakes to fully faired and suspended singlepurpose asphalt weapon. The KR dirttrack frame was a set of tubes into which the engine was bolted. The frame for the late KRTT roadracer,

known as the Lowboy, was an engine around which the frame was tightly wrapped. The engine, which was state of the art (which means average and not all that wonderful) in 1952, should have been a joke by 1968. Sidevalves? The only other maker of such devices by then surely was Briggs & Stratton. Except that the wizards inside the Harley shop and out massaged and experimented, and by the end had 65 horsepower wrung from the poor little 45-cubic-inch engines. And they’d go 200 miles plus a victory lap at that output.

Add to this Calvin Rayborn, a onetime shagger, a motorcycle messenger, from San Diego. Rayborn was a cheerful, outgoing kid with a passion for roadracing and the good luck to be backed by Len Andres, the Harley dealer who’d tuned his son Brad to 12 national wins a decade earlier. Brad was retired from racing to run the family’s real estate empire, Len was bored and Cal was hungry and possessed of as much natural talent as ever threw a leg over a motorcycle.

The combination gave the HarleyDavidson roadrace team two backto-back Finest Hours.

The first was Daytona 1968. The rules allowed 750cc for sidevalves, of which

the KR was the only example still living, and 500cc for overhead valves, meaning Triumph and BSA and Norton and peers. The rules were quaint, one could argue they were out of date, but they made for great racing. The KRTT was fast qualifier, in the hands of teamster Roger Reiman, with 149 mph. Just behind was the Yamaha 350 Twin, 147, and then the Triumph at 135 and the BSA with 130. Two hundred miles later, Rayborn had lapped the field. “Win” wasn’t a big enough word.

In 1969 came a different Big Day. The KRTTs weren’t as fast as they’d been, with a best of 144, Rayborn up. A Yamaha had the pole, at 150; with next to that a Suzuki, at 147. On race day, it rained. The race was postponed, the H-D turners solved the problem, the rivals had things fall off and blow up or both, and Rayborn won again, on stamina instead of speed.

Then, eclipse. Younger fans haven’t heard about Harley-Davidson roadracing because the rules changed. First, the 750 two-stroke Fours outpowered the four-stroke Twins. Next, the rules allowed pure racing engines to qualify in lots of 25, not 200. Yamaha and Honda could afford such a program, Harley and Triumph couldn’t.

Finally, because dirt and pavement machines were now so different, the AMA broke the national series into two championships: The new Harley racer, the XR750, was supreme on the dirt in 1972 and still is, while the XRTT roadracer, couldn’t do the job, nor did the 250, 350 and 500cc two-strokes Harley built and raced overseas with some success.

Time for one more Glorious Example. In 1983, H-D introduced the XR1000, a mix of Sportster body and frame and lower end with XR heads and carbs. The factory team missed roadracing and the marketing men missed Daytona Beach, so the racing shop built a device named “Lucifer’s Hammer,” after a Celtic legend. It was an XR1000 the way Dale Earnhardt’s NASCAR mount is a Chevrolet sedan. Never mind, both conform to the rules.

And in the 1983 Daytona Battle of the Twins, three-time dirt champion Jay Springsteen pulled up next to the defending titlist Ducati, nodded, and pulled away with contemptuous ease. The same machine, ridden by Gene Church, went on to take the series title three years running.

In sum, 10 years later, when the VR1000 brings home its first roadrace trophy, the guys in the red brick building on Juneau Ave. back in Milwaukee will need to do some shuffling.

The trophy case is already full. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue