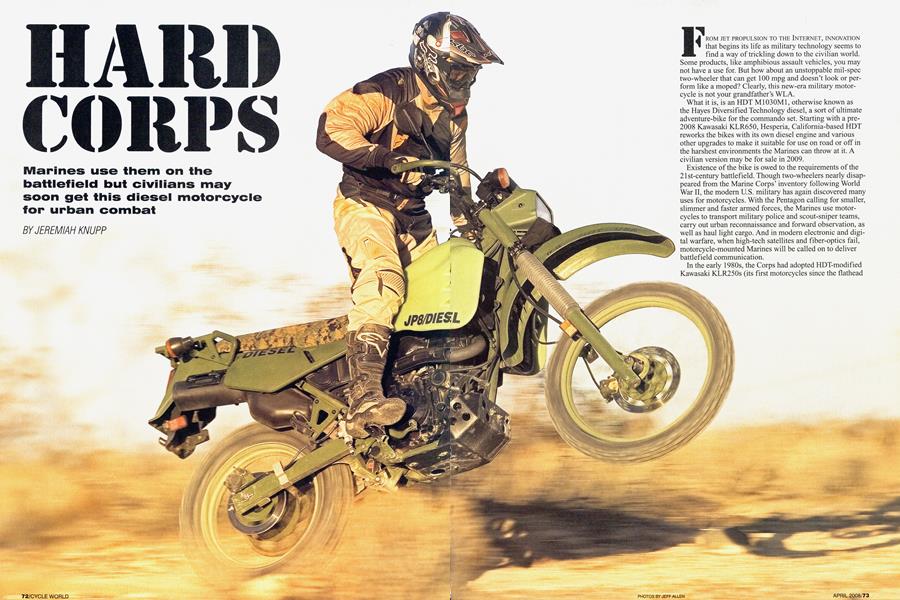

HARD CORPS

Marines use them on the battlefield but civilians may soon get this diesel motorcycle for urban combat

JEREMIAH KNUPP

FROM JET PROPULSION TO THE INTERNET, INNOVATION that begins its life as military technology seems to find a way of trickling down to the civilian world. Some products, like amphibious assault vehicles, you may not have a use for. But how about an unstoppable mil-spec two-wheeler that can get 100 mpg and doesn’t look or perform like a moped? Clearly, this new-era military motorcycle is not your grandfather’s WLA.

What it is, is an HDT M1030M1, otherwise known as the Hayes Diversified Technology diesel, a sort of ultimate adventure-bike for the commando set. Starting with a pre-2008 Kawasaki KLR650, Hesperia, California-based HDT reworks the bikes with its own diesel engine and various other upgrades to make it suitable for use on road or off in the harshest environments the Marines can throw at it. A civilian version may be for sale in 2009.

Existence of the bike is owed to the requirements of the 21st-century battlefield. Though two-wheelers nearly disappeared from the Marine Corps’ inventory following World War II, the modern U.S. military has again discovered many uses for motorcycles. With the Pentagon calling for smaller, slimmer and faster armed forces, the Marines use motorcycles to transport military police and scout-sniper teams, carry out urban reconnaissance and forward observation, as well as haul light cargo. And in modem electronic and digital warfare, when high-tech satellites and fiber-optics fail, motorcycle-mounted Marines will be called on to deliver battlefield communication.

In the early 1980s, the Corps had adopted HDT-modified Kawasaki KLR250s (its first motorcycles since the flathead Harleys of World War II). These little machines gave a decade of service that included operations during Desert Storm. But by the mid-’90s, the fleet was worn out. This fact, combined with the 1997 Department of Defense “Single Battlefield Fuel Requirement” directive (stipulating the kerosene-based turbine/aviation fuel known as JP8 be used in all air and ground equipment) forced the Corps to look for a replacement.

“Our motorcycles were some of the last vehicles in the military that ran on gasoline,” said Jack Heric, retired Marine, off-road rider and the civilian Transport Motorcycle Project Officer responsible for acquiring a diesel motorcycle for the Corps. “Our only choice was to get rid of them or make them diesel.”

HDT’s version was the final selection from the nearly 40 proposals submitted to the Marines. The first bikes were, in fact, gasoline-powered KLR650s suitably modified for battlefield use, including heavy-duty front and rear suspension, blacked-out lights, modified handguards and tires with a more aggressive tread.

Of course, the larger bike was chosen with an eye for the future, based on the single-fuel directive.

“The Kawasaki had the frame size that we knew we would need for a diesel engine,” says Heric.

Five-hundred and twenty-two of the gas-powered KLRs, known as M1030Bls, were delivered to the Marines beginning in 1998. They were immediately put into use, with many seeing service in Afghanistan and the initial ground invasion of Iraq in March, 2003. The Marines quickly discovered something that civilian riders have known for a long time:

The big KLR has one of the best combinations of off-road toughness and on-road ability.

While the gasoline Ml030s were making tracks in the sand, HDT began looking for a compact diesel engine that would fit in that machine’s frame. The company hired an outside design consultant who was developing a compact, high-performance diesel motorcycle engine in England. The resulting powerplant is a liquidcooled, four-valve, four-stroke Single displacing 61 lcc. Fuel is delivered via mechanically controlled indirect fuel-injection (that is, not direct to the cylinder like a lot of modem diesels). Published performance figures are 30 hp at 5700 rpm (down about 18 hp from the gasoline KLR). Torque is 33 ft.-lb. at 4200 rpm, compared to the 33 ft.-lb. at 5050 rpm on the stock KLR.

“We want to make it clear that this is not a ‘conversion,’ but a completely new engine from the ground up,” explained HDT boss Fred Hayes, himself a former off-road racer whose company developed performance mods for enduro racebikes during the ’70s. “It is a purpose-built diesel motorcycle engine that only uses the transmission and electrical system from the gasoline Kawasaki engine.”

Production of the diesel motorcycles began in March,

2006, with the gasoline-powered KLR fleet being sent back to HDT to be “remanufactured.” By November of that year, the first diesel KLRs were in the hands of U.S. Marines.

The Ml weighs 369 pounds dry, making it 11 pounds heavier than the gasolinepowered military model and 32 pounds heavier than the civilian “old-style” pre-2008 KLR on which it was based. While physical dimensions are nearly identical to a civilian KLR, the military version has about an inch and a half of additional ground clearance and a correspondingly higher seat.

Official performance figures released by HDT give a 0-60-mph time of 9.7 seconds with a top speed of “over 90 mph.” When completed, 448 of the gasoline-powered Marine motorcycles will have been remanufactured into the diesel version.

Not a design requirement but a “side benefit,” as Heric calls it, is the engine’s fuel economy. HDT’s official test figures claim 96 mpg at 55 mph (nearly twice that of a gasoline-powered KLR), giving it a range of 400-plus miles from its 4.25-gallon fuel tank. According to Heric, Marine riders average between 90 and 110 mpg under normal use.

So what does all this mean to us civilians who will never pass through Parris Island to get our hands on an olive-drab diesel Kawasaki? With the rising price of oil, new interest is being shown in diesel-powered vehicles (HDT’s multifuel engine design can also run on bio-diesel). In 2005, the company announced plans to release a civilian model of the Ml030 and have since been flooded with interest from around the world.

“The response has been overwhelming, and if we started production on the commercial model today, production couldn’t keep up with the demand,” Hayes said.

Hayes adds that the bio-diesel industry in particular has shown keen interest in a vehicle that yields record-breaking performance on diesel power. Since 2004, HDT has captured and held eight FIM and four AMA land-speed records in four different classes at the Bonneville Speed Trials (Fred Hayes himself has been one of the pilots). The saltflats record breakers were all running on B20 bio-diesel, an organic/petroleum mix.

Hayes said the company now expects it will be at least 2009 before the first civilian models are available. “The base-unit” for the civilian version, which HDT calls the MD670F, is based on the new Kawasaki KLR650 introduced as a 2008 model. It will feature a larger-displacement engine with higher performance than its Marine counterpart. Final specifications are yet to be released, but a dry weight of less than 400 pounds and a range of more than 600 miles is expected. Price has not been determined-though the original commercial model that didn’t reach production was slated to cost nearly $19,000-and Hayes expects initial production to be limited to 200 machines.

While HDT works on several other diesel-engine projects (one for a four-wheel light-utility vehicle, another for a remote-controlled observation plane, and even a turbocharged 1400cc V-Twin for a cruiser), the main focus remains the military contract.

A small company, HDT can’t hope to change the world on its own. The expected limited production numbers and high price of the MD670F will keep its diesel motorcycle out of the hands of the average rider. But Hayes and company have laid the groundwork for a revolution in the industry by proving that diesel is a practical power source for motorcycles.

Jeremiah Knupp is a freelance writer who uses motorcycle journalism to support his addiction to faraway places with good food, bad roads and hotels that cost less than $10 a night. His experience riding in Central and South America gave him an appreciation for anything with flat paint, crash guards and the ability to go more than 250 miles on a tank offuel. This is his first story for Cycle World.