THE RECORD THAT NEVER WAS

HISTORY HAS A STRANGE WAY of changing, depending upon whos telling it. A good example is the belief held by most motorcycle historians that by the end of 1923, the fastest man in the world on two wheels was an Englishman. Claude Temple, who had ridden a V-Twin Temple-Anzani to a speed of 108.84 mph. was the officially recognized FIM (Fédération Internationale Motocycliste) motorcycle world speed record holder.

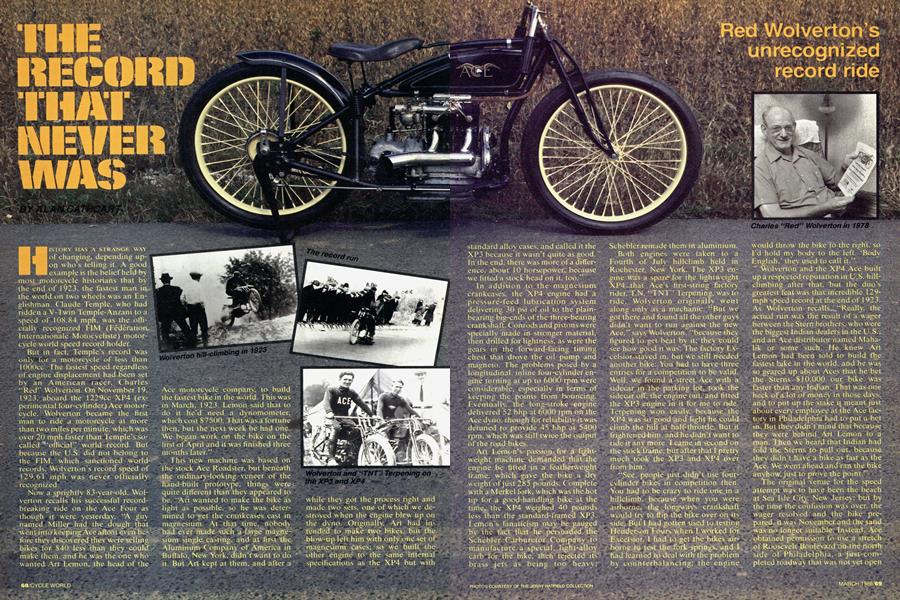

But in fact. Temple’s record was only for a motorcycle of less than lOOOcc. The fastest speed regardless of engine displacement had been set by an American racer, Charles “Red” Wolverton. On November 19, 1923. aboard the 1229cc XP4 (experimental four-cylinder) Ace motorcycle, Wolverton became the first man to ride a motorcycle at more than two miles per minute, which was over 20 mph faster than Temple’s socalled ^‘official” world record. But because the U.S. did not belong to the FIM. which sanctioned world records, Wolverton's record speed of 129.61 mph was never officially recognized.

Now a sprightly 83-year-old. Wolverton recalls his successful recordbreaking ride on the Ace Four as though it were yesterday. “A guy named Miller had the dough that went into keeping Ace afloat even before they discovered they were selling bikes for $40 less than they could make them, and he was the one who wanted Art Lemon, the head of the

Ace motorcycle company, to build the fastest bike in the world. This was in March, 1923. Lemon said that do it he'd need a dynomometer, w hich cost $7500. That was a fortune then, but the next week he had one. We began work on the bike on the first of April and it was finished three months later.”

This new machine was based on the stock Ace Roadster, but beneath the ordinary-looking veneer of the hand-built prototype, things were quite different than they appeared to be. “Art wanted to make the bike as light as possible, so he was determined to get the crankcases cast in magnesium. At that time, nobody had ever made such a large magnesium single casting, and at first the Aluminum C ompany of America in Buffalo, Newr York, didn't want to do it. But Art kept at them, and after a

while they got the process right and made two sets, one of which we destroyed when the engine blew up on the dyno. Originally, Art had intended to make two bikes, but the blow-up left him with only one set of magnesium cases; so we built the other engine to the same internal specifications as the XP4 but with standard alloy cases, and called it the XP3 because it wasn't quite as good. In the end. there was more of a difference. about 10 horsepower, because we fitted a stock head on it. too."

Red Wolverton's unrecognized record ride

In addition to the magnesium crankcases, the XP4 engine had a pressure-feed lubrication system delivering 30 psi of oil to the plainbearing big-ends of the three-bearing crankshaft. Conrodsand pistons were specially made in stronger material, then drilled for lightness, as were the gears in the forward-facing timing chest that drove the oil pump and magneto. The problems posed by a longitudinal, inline four-cylinder engine turning at up to 6000 rpm were considerable, especially in terms of keeping the points from bouncing. Eventually, the long-stroke engine delivered 52 bhp at 6000 rpm on the Ace dyno. though for reliability it was detuned to provide 45 bhp at 5400 rpm. w hich was still twice the output of the road bikes.

Art Lemon’s passion for a lightweight machine demanded that the engine be fitted in a featherweight frame, which gave the bike a dry weight of just 285 pounds. Complete with a Merkel fork, which was the hot tip for a good-handling bike at the time, the XP4 weighed 40 pounds less than the standard-framed XP3. Lemon's fanaticism may be gauged by the fact that he persuaded the Schebler Carburetor Company to manufacture a special, light-alloy carb for the bike, then rejected its brass jets as being too heavy;

Schebler remade them in aluminium.

Both engines were taken to a Fourth of July hillclimb held in Rochester. New York. The XP3 engine was a spare for the lightweight XP4 that Ace's first-string factory rider, T.N. “TNT" Terpening. w'as to ride. Wolverton originally w'ent along only as a mechanic. “But we got there and found all the other guys didn't want to run against the new Ace." says Wolverton. “because they figured to get beat by it; they could see how good it was. The factory Excelsior stayed in, but we still needed another bike: You had to have three entries for a competition to be valid. Well, w'e found a street Ace with a sidecar in the parking lot. took the sidecar off, the engine out, and fitted the XP3 engine in it for me to ride. Terpening won easily, because the XP4 was so good and light he could climb the hill at half-throttle. But it frightened him. and he didn't want to ride it any more. I came in second on the stock frame, but after that I pretty much took the XP3 and XP4 over from him.

“See, people just didn't use fourcylinder bikes in competition then. You had to be crazy to ride one in a hillclimb. because when you were airborne, the longways crankshaft would try to flip the bike over on its side. But I had gotten used to testing Henderson Fours w hen I worked for Excelsior. I had to get the bikes airborne to test the fork springs, and I had learned to deal with the problem by counterbalancing; the engine

would throw the bike to the right, so I'd hold my body to the left. ‘Body English,’ they used to call it."

Wolverton and the XP4 Ace built up a respected reputation in U.S. hillclimbing after that, but the duo’s greatest feat was that incredible 129mph speed record at the end of 1923. As Wolverton recalls. “Really, the actual run was the result of a wager between the Stern brothers, who were the biggest Indian dealers in the U.S.. and an Ace distributor named Mahalik or some such. He knew Art Lemon had been told to build the fastest bike in the world, and he was so geared up about Aces that he bet the Sterns $10.000 our bike was faster than any Indian. That was one heck of a lot of money in those days, and to put up the stake it meant just about every employee at the Ace factory in Philadelphia had to put a bet in. But they didn’t mind that because they were behind Art Lemon to a man. Then we heard that Indian had told the Sterns to pull out. because they didn't have a bike as fast as the Ace. We wjent ahead and ran the bike anyhow, just to prove the point."

The original venue for the speed attempt was to have been the beach at Sea Isle City. New Jersey; but by the time the confusion was over, the wager resolved and the bike prepared. it was November and the sand was no longer suitable. Instead. Ace obtained permission to use a stretch of Roosevelt Boulevard on the north side of Philadelphia, a just-completed roadway that was not yet open to traffic. “We had cops from the city police department there to supervise everything,” says Wolverton, “but they fell down on the job and let a car through on one of my runs. I got me a real big scare when I saw it heading my way, but we avoided each other in the end. Just as well, because I couldn’t have stopped at those speeds even if I’d wanted to. The only brake we had on the bike was a small, single drum on the rear just to stop from slow speeds.”

Adding difficulty to the record attempt was a curve in the section of boulevard along which the speed runs were made. “I almost lost con-

trol of the XP4 on the bend, when it started weaving from side to side on my first run. Fortunately, I rode with my right hand on the grip and my left hand clamped on the bar, upside down, near the forks. That gave me enough leverage to control the weave, even if I couldn’t stop it altogether. I used a different line through the bend after that and the weave never got too bad.

“We had to make two attempts, with a week or so between the two; there was a screw-up on the timing the first occasion, though it turned out I did 128 mph. It was pretty late in November when we went back,

and I got to 129 mph on the bike pretty quick. I wanted to go again to beat 130, but Art said it was too cold. It was just as well, because when they prepped the bike for the Chicago Show, they found the fork stem had fractured through all but a quarterinch. My next run would have been kinda exciting, that’s for sure.” Wolverton’s record of 129.61 mph on the solo XP4 was complemented by a speed of 106 mph to establish a new sidecar record with the XP3, which had been fitted with a lightweight Flxi sidecar. Unlike FIM regulations, which stipulated two-way runs for record attempts, American rules of the day required a run only in one direction, so that was all Wolverton did. The lack of an FIM sanction doesn’t bother him, however. “The speed was electrically timed and there was a crosswind, so it was a true speed,” he says. “We figured out afterwards that we lost 12 percent of our speed through the increased friction of the new concrete. If we’d run at Daytona or on a salt lake, we’d have beaten 140 mph easy. We wore the tires out just doing a few runs.” After the bike’s remarkable performance, the Ace factory made a splash at the National Motorcycle Show in Chicago in February of 1924, offer-

ing a $ 10,000 wager to any manufacturer that cared to challenge Wolverton’s mark.

And, presumably, Red Wolverton became a national hero after achieving his record, right? “Nope. The next day I was back at work in the Ace factory just like it never happened. They didn’t even send me to the Chicago show. It was all the machine’s doing as far as they were concerned. not the rider’s. People often ask me how much I got paid to set the record. I always tell ’em it was $35 a week and two weeks vacation a year— that’s what I got paid for working there. Never even got a bonus for it.”

Wolverton stayed an Ace employee until the factory moved to Michigan. A native of New Jersey, he remained there and switched to Harley-Davidsons, which he raced in hillclimbs and on dirt tracks until 1937, when he retired after a glorious, 18-year racing career. An accomplished tuner, he stayed active in the sport for another three decades while he was a partner in a Harley franchise in Reading, Pennsylvania. Now he lives near there, 83 years young and still interested in motorcycles. As Wolverton explains it, “Hey, people won’t let me forget. And I don't want to!” ES

View Full Issue

View Full Issue