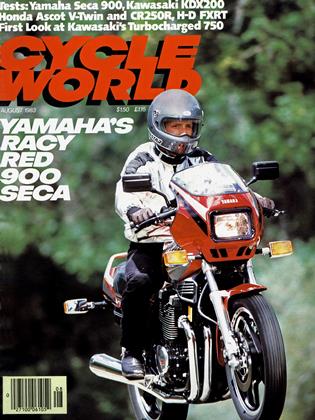

KAWASAKI TURBO 750

EASILY THE FASTEST TURBOBIKE, THE KAWASAKI IS A CONTENDER FOR WORLD'S QUICKEST MOTORCYCLE

In one important way, Kawasaki's 750 Turbo is different from all those other turbos. It is very, very fast. Or so it would seem at the brief introduction offered by Kawasaki at a racetrack in Austria.

Kawasaki bases its new turbocharged bike on the successful GPz750. Onto a 750 GPz is hung the turbocharger, additional fairing bodywork, beefier suspension and brake components and an electronic fuel injection system. Then it’s painted red and black.

As a result of this added equipment, the 750 Turbo puts out about 112 bhp at 9000 rpm. That’s good enough to give the Turbo equivalent performance to Kawasaki’s GPzl 100. Kawasaki says the Turbo is quick enough to turn a 10.9 sec. quarter-mile. At the Austrian test track, prototype Turbos weren’t quite that quick. The best performance anyone obtained with one was a 11.25 sec. quartermile. But of the several GPzl 100s also there, the best performance was a 11.38 sec. quarter-mile, so the Turbo may be quicker on the dragstrip, when production bikes are available for testing.

A day of lapping the Salzburgring showed the Turbo to be a very close match for the GPzl 100 on a road course, at least that road course. Lap times were, for the most part, the same for 1100 and 750 Turbo, but some riders preferred riding one bike, some the other.

How the Turbo operates is very much different from the 1100. Kawasaki’s performance figures show the Turbo producing more power from about 4000 rpm to a little over 7000 rpm, with the bigger motor producing more peak power and better power at low engine speeds. But that range of 4000 to over 7000 rpm is wide, and it’s a useable range, at least on a racetrack, where the Turbo can rocket out of corners with more vigor than the 1100.

Going into corners and through corners the Turbo feels unlike the standard GPz750 or 1100. It is a tight handling bike, and the suspension has stiffer springs and stronger damping than the normally aspirated Kawasaki. Stability it has. On high speed, bumpy corners the llOOcc Kawasaki would wiggle and weave and then settle down. The Turbo just knifes through, bouncing the rider off the seat on a hard bump, but never shaking its bars. At high speeds it is particularly resistant to changing direction, requiring enormous force on the short multi-piece handlebars to go around corners. Once aimed, the Turbo is steady and little affected by bumps and dips. On smooth corners it will touch pegs and stands at the limits, but on bumpy corners the bottom of the fairing scrapes along the ground at the limits.

Perhaps the most noticeable difference between the Turbo and other sports Kawasakis is the brake feel. It’s excellent. Two fingers with light pressure can easily and controllably stop the Kawasaki at any rate desired. There is no flex in the lever, and almost no dive in the front end. This performance isn’t the result of an entirely new brake system, but is achieved with a little careful reworking of the parts used on other Kawasakis. The Turbo gets the discs, calipers and pads from the 1100 GPz, but the brake lines are made of synthetic braided fiber and lined with Teflon. On the Turbo, the minimum anti-dive setting is the same as the maximum setting on the GPz750, and it extends up through four settings from that. The result is a solid lever, enormous braking power, and minimal brake dive.

What a racetrack doesn’t demonstrate is how a motorcycle will work on the road, starting up cold in the morning, riding through traffic with the engine idling, then taking off from a stop sign. A little exploring in the infield showed the Kawasaki Turbo to work much like any other turbocharged motorcycle. Boost wasn’t noticeable below 5000 rpm. Then, suddenly, the motorcycle is transformed. Until that point, the tach needle moves like an hourglass. After boost, it moves like popcorn.

Each of the four Turbo manufacturers has some bit of hardware that is intended to reduce the dreaded turbo lag. On the Kawasaki, it’s the mounting of the turbo, in front of the engine. That keeps the exhaust pipes from the engine to the turbo short, and that reduces the amount of heat energy lost through the tubes. Other tubes wrap from the air filter (housed just outboard of the countershaft sprocket) to the turbo, and from the turbo back to the airbox. From the airbox, short intake tubes hold the fuel injectors and induct the mixture.

Kawasaki’s digital electronic fuel injection has been used on the GPzllOO before, and now on the Turbo 750. It has the usual collection of sensors and wires and uses a small computer to control the injectors.

A thorough mechanical massage has been given the Turbo’s engine to handle the additional power, and to make the most of the turbo. Compression is a low 7.8:1. Cam timing is revised for less duration, overlap and lift. The standard GPz750 cam has 286° of duration, and the Turbo has 254° and 260° on intake and exhaust, with a millimeter less lift. Gear ratios on the primary chain, transmission gears and final drive have been juggled to take advantage of the greater horsepower.

The tricks that boost power on naturally aspirated engines aren’t so important on turbocharged engines, so the Turbo Kawasaki doesn’t have the special combustion chamber, hand porting, or big valves of the GPz750. Instead, it gets the standard KZ650 cylinder head, with smaller valves and ports.

What causes this bike to breathe well isn’t a big, clean induction system, it’s the Hitachi turbocharger. With a 50mm turbine and 47mm compressor, it is not the smallest turbocharger found on a motorcycle. It delivers up to 10 psi of boost before the integral wastegate begins opening. To keep it spinning, the Kawasaki has a higher capacity oil pump, with a scavenging pump for the turbocharger bearings. In addition to the wastegate, the fuel injection stops pumping fuel into the engine if the boost gets too high.

There may be a way around this, however. Kawasaki is developing a high performance kit for racetrack use. It will increase the boost and recalibrate the fuel injection to work with the higher boost. How much additional power the modified 750 will have, Kawasaki technicians wouldn’t say.

As it is, the 750 Turbo is an impressively fast motorcycle. Kawasaki claims that “under proper conditions, the Kawasaki may be the fastest production streetbike ever built.” Those are strong words. And the Turbo is a strong.motorcycle. Considering its performance in relationship to the GPzllOO, the Turbo is likely to be stronger than any other motorcycle at high altitudes. Even at Salzburg, a measly 1200 ft. above sea level, the performance appeared to be a match for anything.

So. The 750 Turbo can easily lay claim to being the fastest turbo-bike in production. It also may be the lightest, with a claimed dry weight of 514 lb. and a ready-to-ride weight around 530 lb. Price is, at this time, unknown. Kawasaki spokesmen expect it to sell for no more than the GPzl 100, maybe a coujble of hundred dollars less.

At last the turbo promise may be fulfilled. The Kawasaki 750 Turbo has the performance of an 1 lOOcc superbike, but without the weight and maybe without the cost. If the Kawasaki were the first turbocharged motorcycle to see production, many of our ideas about turbo-bikes might be different. Instead, it follows three other bikes that offered successively better performance, but all without commercial success. Now there’s a fourth turbo, and it could be better than the last three in some important ways.

This is important. It demonstrates that motorcycles, particularly turbocharged motorcycles, are not a mature technology. There is progress being made, still.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Up Front

August 1983 -

Letters

LettersCycle World Letters

August 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

August 1983 -

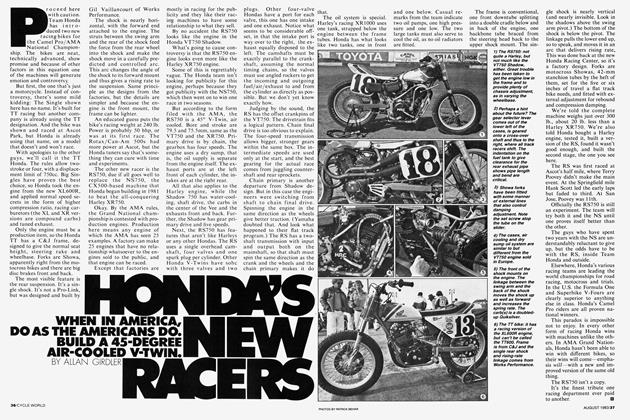

Competition

CompetitionHonda's New Racers

August 1983 By Allan Girdler -

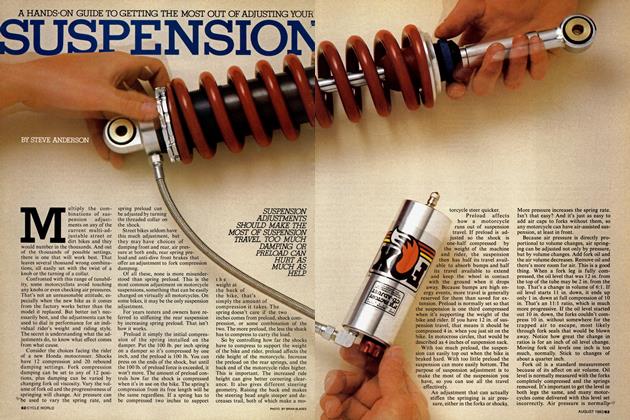

Technical

TechnicalA Hands-On Guide To Getting the Most Out of Adjusting Your Suspension

August 1983 By Steve Anderson -

Features

FeaturesParis-Dakar

August 1983 By Patrick Behar