PARIS-DAKAR

A sense of adventure, the dream of empty beaches and 6500 miles in 20 days.

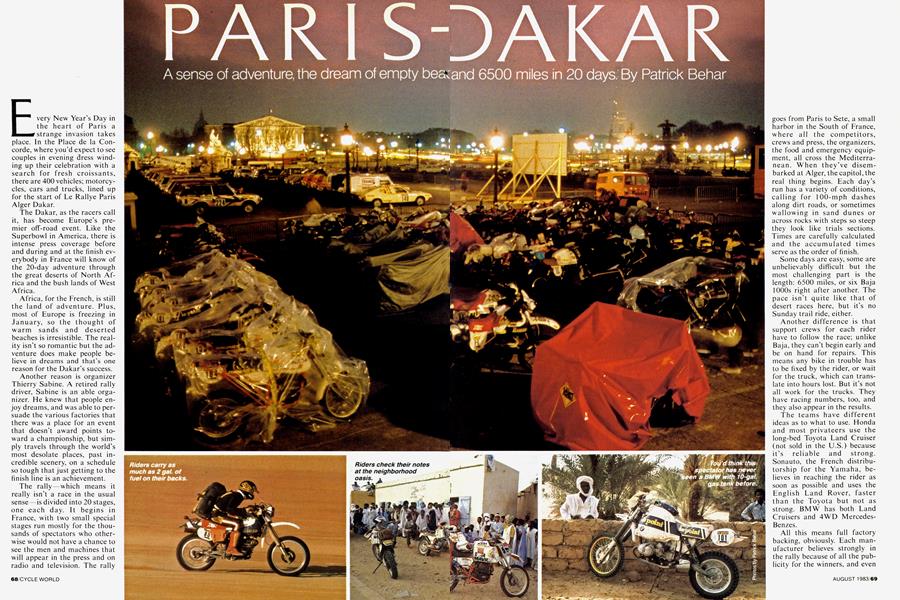

Every New Year's Day in the heart of Paris a strange invasion takes place. In the Place de la Concorde, where you’d expect to see couples in evening dress winding up their celebration with a search for fresh croissants, there are 400 vehicles; motorcycles, cars and trucks, lined up for the start of Le Rallye Paris Alger Dakar.

The Dakar, as the racers call it, has become Europe’s premier off-road event. Like the Superbowl in America, there is intense press coverage before and during and at the finish everybody in France will know of the 20-day adventure through the great deserts of North Africa and the bush lands of West Africa.

Africa, for the French, is still the land of adventure. Plus, most of Europe is freezing in january, so the thought of warm sands and deserted beaches is irresistible. The reality isn’t so romantic but the adventure does make people believe in dreams and that’s one reason for the Dakar’s success.

Another reason is organizer Thierry Sabine. A retired rally driver, Sabine is an able organizer. He knew that people enjoy dreams, and was able to persuade the various factories that there was a place for an event that doesn’t award points toward a championship, but simply travels through the world’s most desolate places, past incredible scenery, on a schedule so tough that just getting to the finish line is an achievement.

The rally—which means it really isn’t a race in the usual sense—is divided into 20 stages, one each day. It begins in France, with two small special stages run mostly for the thousands of spectators who otherwise would not have a chance to see the men and machines that will appear in the press and on radio and television. The rally goes from Paris to Sete, a small harbor in the South of France, where all the competitors, crews and press, the organizers, the food and emergency equipment, all cross the Mediterranean. When they’ve disembarked at Alger, the capitol, the real thing begins. Each day’s run has a variety of conditions, calling for 100-mph dashes along dirt roads, or sometimes wallowing in sand dunes or across rocks with steps so steep they look like trials sections. Times are carefully calculated and the accumulated times serve as the order of finish.

Patrick Behar

Some days are easy, some are unbelievably difficult but the most challenging part is the length: 6500 miles, or six Baja 1000s right after another. The pace isn’t quite like that of desert races here, but it’s no Sunday trail ride, either.

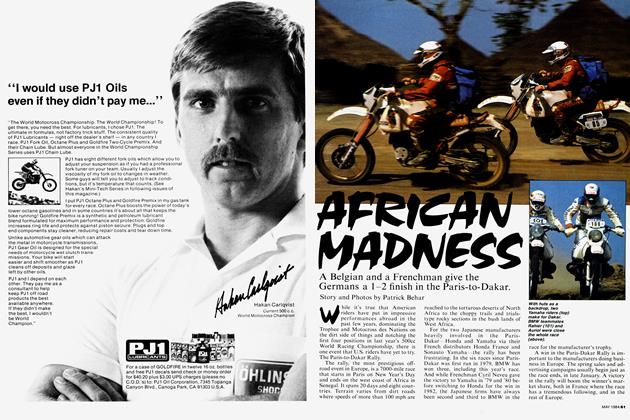

Another difference is that support crews for each rider have to follow the race; unlike Baja, they can’t begin early and be on hand for repairs. This means any bike in trouble has to be fixed by the rider, or wait for the truck, which can translate into hours lost. But it’s not all work for the trucks. They have racing numbers, too, and they also appear in the results.

The teams have different ideas as to what to use. Honda and most privateers use the long-bed Toyota Land Cruiser (not sold in the U.S.) because it’s reliable and strong. Sonauto, the French distributorship for the Yamaha, believes in reaching the rider as soon as possible and uses the English Land Rover, faster than the Toyota but not as strong. BMW has both Land Cruisers and 4WD MercedesBenzes.

All this means full factory backing, obviously. Each manufacturer believes strongly in the rally because of all the publicity for the winners, and even the losers. Honda, for example, is reducing its enduro program to just two events, one of which will be the Dakar. A good showing in the rally sells motorcycles, especially in Europe where trail bikes are very popular in the cities. Winning Paris-Dakar means a sales boom in late winter, when otherwise sales are very slow. .(Like us, Europeans do most of their buying in the spring.)

The riders are not household names in the U.S. although several of them have raced in the Baja 1000. Hubert Auriol, this year’s Dakar winner; and Cyril Neveu, the rally’s only threetime winner, have both raced in Mexico, as-have Christine Martin and Veronique Anquetil, who are very strong in the women’s class in the Dakar.

The Yamaha factory is still looking for its first win as a factory, although Neveu won on a Yamaha as a privateer. BMW isn’t much involved in racing in Europe but they have won Dakar twice, including this year. This year BMW had five official entries: Auriol, French journalist George Fenouil (who also organizes a similar rally in Egypt), Paris police officer Raymond Loizeaux, world class motocrosser Gaston Rahier (not surprisingly he was fastest in the rough sections in Algeria), and Herbert Scheck, the giant German who rode the ISDT 25 times and was famous for bare-handed tire changes. Rahier retired with a case smashed on a rock. Iron man Scheck had to quit riding when he broke a collarbone but he travelled with the BMW support crew the rest of the way because he'd built the engine in his bike and wanted to make sure it got proper care.

The vast majority of the riders, though, are amateurs, enthusiasts who have local enduro experience and take off from work just for the challenge. Winner of the women’s class this year was Maris Ertaud, art attendant on Air France. Some of the privateers don’t have a chase truck or crew, so they must carry all their parts and tools with them, or rely on other crews or help from the factory that made their bikes. When? the Dakar began, it was a ride for a bunch of buddies, but now it’s truly professional and will be won only by the professionals. That, however, doesn’t bother the hopefuls. They can try for a good showing and perhaps that will mean a place on a factory team next year.

The machines are normal enduro style, carried to an extreme. Fuel stops are distant and one of the few ways to make up time is to not stop for gas, so most riders use fourstroke Singles, as in Honda XR, Yamaha TT, or Rotax-powered KTM. BMW naturally uses its opposed Twin in a special frame and this year one man rode a Moto Morini 500 V-Twin. At the small end of the factory effort, there’s the Barigo, a French-made bike with Rotax engine. Owner/manufacturer Patrick Barigault served as pit crew for some 20 customers and in the end one of his bikes was 11th overall, which earned him some mention in the news.

Would an American do well in the Dakar? Not in terms of publicity, no; the rally is as little-known here as it is famous in Europe. But if it is to enjoy some of the most beautiful scenery and most difficult terrain, or to take part in the adventure just because it’s there, well, for those interested the next rally starts at the Place de la Concorde, Paris, on 1 January, 1984.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

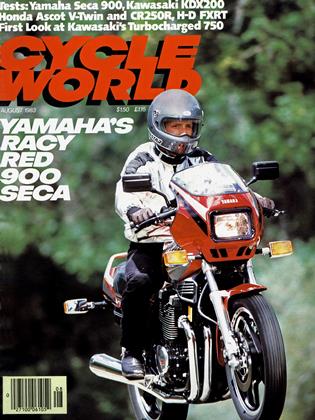

DepartmentsCycle World Up Front

August 1983 -

Letters

LettersCycle World Letters

August 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

August 1983 -

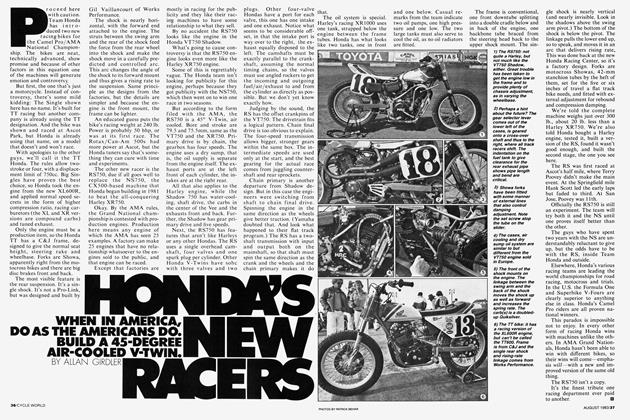

Competition

CompetitionHonda's New Racers

August 1983 By Allan Girdler -

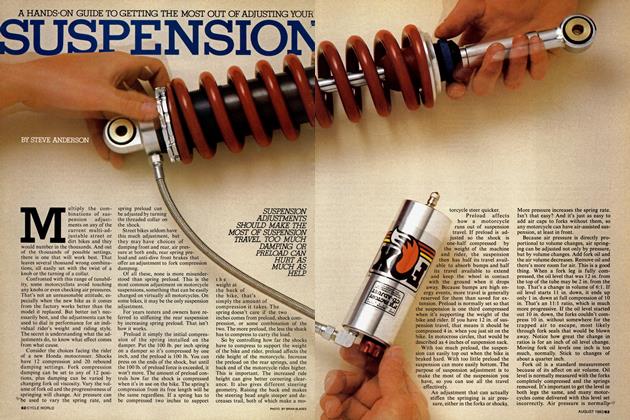

Technical

TechnicalA Hands-On Guide To Getting the Most Out of Adjusting Your Suspension

August 1983 By Steve Anderson -

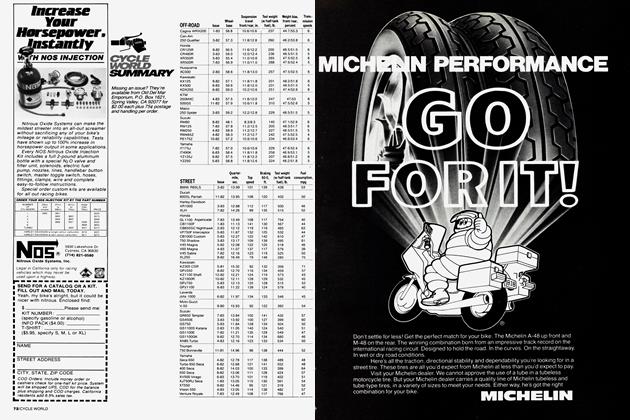

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

August 1983