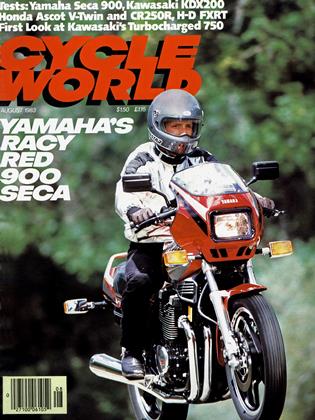

HONDA'S NEW RACERS

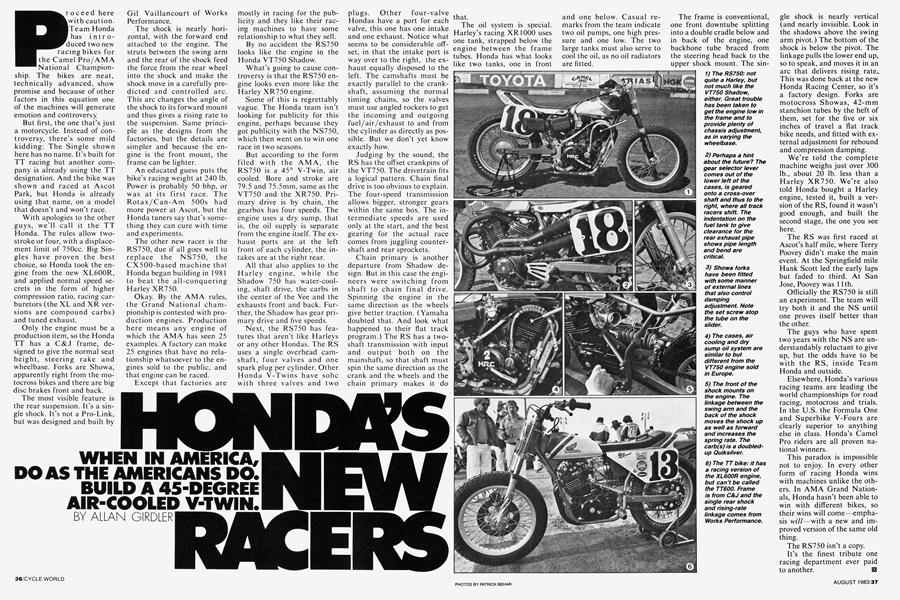

WHEN IN AMERICA, DO AS THE AMERICANS DO. BUILD A 45-DEGREE AIR-COOLED V-TWIN.

ALLAN GIRDLER

Proceed here with caution. Team Honda has introduced two new racing bikes for the Camel Pro/AMA National Championship. The bikes are neat, technically advanced, show promise and because of other factors in this equation one of the machines will generate emotion and controversy.

But first, the one that’s just a motorcycle. Instead of controversy, there’s some mild kidding: The Single shown here has no name. It’s built for TT racing but another company is already using the TT designation. And the bike was shown and raced at Ascot Park, but Honda is already using that name, on a model that doesn’t and won’t race.

With apologies to the other guys, we’ll call it the TT Honda. The rules allow two-stroke or four, with a displacement limit of 750cc. Big Singles have proven the best choice, so Honda took the engine from the new XL600R, and applied normal speed secrets in the form of higher compression ratio, racing carburetors (the XL and XR versions are compound carbs) and tuned exhaust.

Only the engine must be a production item, so the Honda TT has a C&J frame, designed to give the normal seat height, steering rake and wheelbase. Forks are Showa, apparently right from the motocross bikes and there are big disc brakes front and back.

The most visible feature is the rear suspension. It’s a single shock. It’s not a Pro-Link, but was designed and built by Gil Vaillancourt of Works Performance.

The shock is nearly horizontal, with the forward end attached to the engine. The struts between the swing arm and the rear of the shock feed the force from the rear wheel into the shock and make the shock move in a carefully predicted and controlled arc. This arc changes the angle of the shock to its forward mount and thus gives a rising rate to the suspension. Same principle as the designs from the factories, but the details are simpler and because the engine is the front mount, the frame can be lighter.

An educated guess puts the bike’s racing weight at 240 lb. Power is probably 50 bhp, or was at its first race. The Rotax/Can-Am 500s had more power at Ascot, but the Honda tuners say that’s something they can cure with time and experiments.

The other new racer is the RS750, due if all goes well to replace the NS750, the CX500-based machine that Honda began building in 1981 to beat the all-conquering Harley XR750.

Okay. By the AMA rules, the Grand National championship is contested with production engines. Production here means any engine of which the AMA has seen 25 examples. A factory can make 25 engines that have no relationship whatsoever to the engines sold to the public, and that engine can be raced.

Except that factories are iftostly in racing for the publicity and they like their racing machines to have some relationship to what they sell.

By no accident the RS750 looks like the engine in the Honda VT750 Shadow.

What’s going to cause controversy is that the RS750 engine looks even more like the Harley XR750 engine.

Some of this is regrettably vague. The Honda team isn’t looking for publicity for this engine, perhaps because they got publicity with the NS750, which then went on to win one race in two seasons.

But according to the form filed with the AMA, the RS750 is a 45° V-Twin, air cooled. Bore and stroke are 79.5 and 75.5mm, same as the VT750 and the XR750. Primary drive is by chain, the gearbox has four speeds. The engine uses a dry sump, that is, the oil supply is separate from the engine itself. The exhaust ports are at the left front of each cylinder, the intakes are at the right rear.

All that also applies to the Harley engine, while the Shadow 750 has water-cooling, shaft drive, the carbs in the center of the Vee and the exhausts front and back. Further, the Shadow has gear primary drive and five speeds.

Next, the RS750 has features that aren’t like Harleys or any other Hondas. The RS uses a single overhead camshaft, four valves and one spark plug per cylinder. Other Honda V-Twins have sohc with three valves and two plugs. Other four-valve Hondas have a port for each valve, this one has one intake and one exhaust. Notice what seems to be considerable offset, in that the intake port is way over to the right, the exhaust equally disposed to the left. The camshafts must be exactly parallel to the crankshaft, assuming the normal timing chains, so the valves must use angled rockers to get the incoming and outgoing fuel/air/exhaust to and from the cylinder as directly as possible. But we don’t yet know exactly how.

Judging by the sound, the RS has the offset crankpins of the VT750. The drivetrain fits a logical pattern. Chain final drive is too obvious to explain. The four-speed transmission allows bigger, stronger gears within the same box. The intermediate speeds are used only at the start, and the best gearing for the actual race comes from juggling countershaft and rear sprockets.

Chain primary is another departure from Shadow design. But in this case the engineers were switching from shaft to chain final drive. Spinning the engine in the same direction as the wheels give better traction. (Yamaha doubted that. And look what happened to their flat track program.) The RS has a twoshaft transmission with input and output both on the mainshaft, so that shaft must spin the same direction as the crank and the wheels and the chain primary makes it do that.

The oil system is special. Harley’s racing XR1000 uses one tank, strapped below the engine between the frame tubes. Honda has what looks like two tanks, one in front and one below. Casual remarks from the team indicate two oil pumps, one high pressure and one low. The two large tanks must also serve to cool the oil, as no oil radiators are fitted.

The frame is conventional, one front downtube splitting into a double cradle below and in back of the engine, one backbone tube braced from the steering head back to the upper shock mount. The single shock is nearly vertical (and nearly invisible. Look in the shadows above the swing arm pivot.) The bottom of the shock is below the pivot. The linkage pulls the lower end up, so to speak, and moves it in an arc that delivers rising rate. This was done back at the new Honda Racing Center, so it’s a factory design. Forks are motocross Showas, 42-mm stanchion tubes by the heft of them, set for the five or six inches of travel a flat track bike needs, and fitted with external adjustment for rebound and compression damping.

We’re told the complete machine weighs just over 300 lb., about 20 lb. less than a Harley XR750. We’re also told Honda bought a Harley engine, tested it, built a version of the RS, found it wasn’t good enough, and built the second stage, the one you see here.

The RS was first raced at Ascot’s half mile, where Terry Poovey didn’t make the main event. At the Springfield mile Hank Scott led the early laps but faded to third. At San Jose, Poovey was 11th.

Officially the RS750 is still an experiment. The team will try both it and the NS until one proves itself better than the other.

The guys who have spent two years with the NS are understandably reluctant to give up, but the odds have to be with the RS, inside Team Honda and outside.

Elsewhere, Honda’s various racing teams are leading the world championships for road racing, motocross and trials. In the U.S. the Formula One and Superbike V-Fours are clearly superior to anything else in class. Honda’s Camel Pro riders are all proven national winners.

This paradox is impossible not to enjoy. In every other form of racing Honda wins with machines unlike the others. In AMA Grand Nationals, Honda hasn’t been able to win with different bikes, so their wins will come—emphasis will—with a new and improved version of the same old thing.

The RS750 isn’t a copy.

It’s the finest tribute one racing department ever paid to another.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Up Front

August 1983 -

Letters

LettersCycle World Letters

August 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

August 1983 -

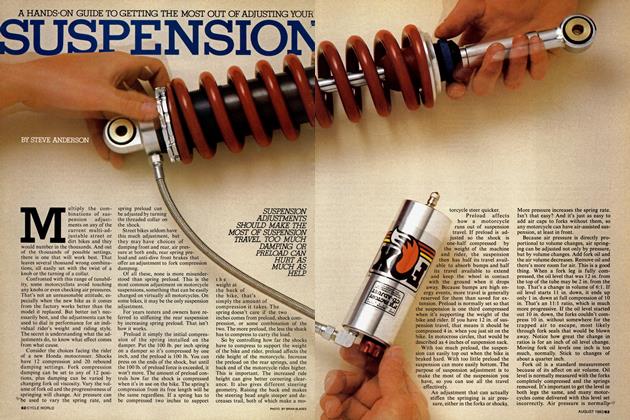

Technical

TechnicalA Hands-On Guide To Getting the Most Out of Adjusting Your Suspension

August 1983 By Steve Anderson -

Features

FeaturesParis-Dakar

August 1983 By Patrick Behar -

Departments

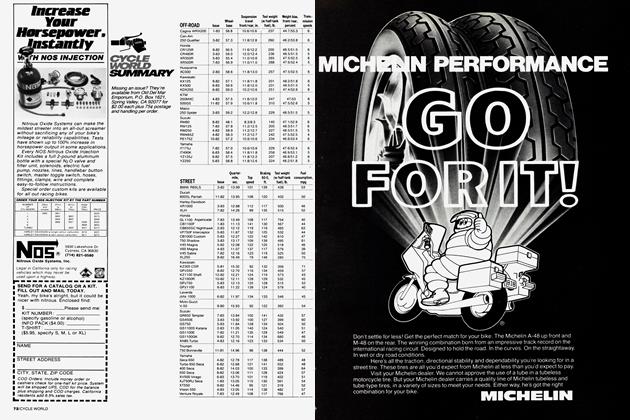

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

August 1983