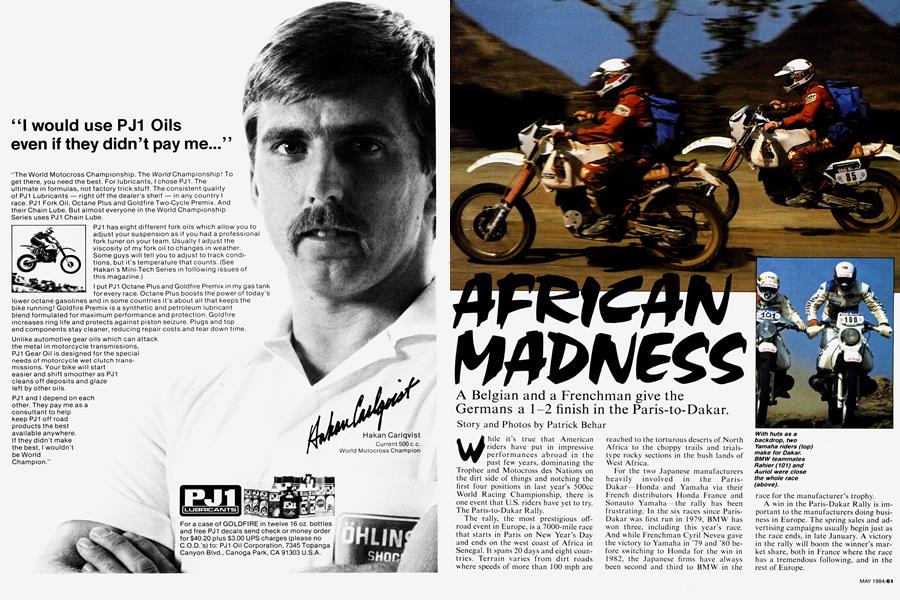

AFRICAN MADNESS

A Belgian and a Frenchman give the Germans a 1-2 finish in the Paris-to-Dakar.

Patrick Behar

While it's true that American riders have put in impressive performances abroad in the past few years, dominating the Trophee and Motocross des Nations on the dirt side of things and notching the first four positions in last year's 500cc World Racing Championship, there is one event that U.S. riders have yet to try. The Paris-to-Dakar Rally.

The rally, the most prestigious offroad event in Europe, is a 7000-mile race that starts in Paris on New Year’s Day and ends on the west coast of Africa in Senegal. It spans 20 days and eight countries. Terrain varies from dirt roads where speeds of more than 100 mph are

reached to the torturous deserts of North Africa to the choppy trails and trialstype rocky sections in the bush lands of West Africa.

For the two Japanese manufacturers heavily involved in the ParisDakar Honda and Yamaha via their French distributors Honda France and Sonauto Yamaha—the rally has been frustrating. In the six races since ParisDakar was first run in 1979, BMW has won three, including this year’s race. And while Frenchman Cyril Neveu gave the victory to Yamaha in ’79 and ’80 before switching to Honda for the win in 1982, the Japanese firms have always been second and third to BMW in the

race for the manufacturer’s trophy.

A win in the Paris-Dakar Rally is important to the manufacturers doing business in Europe. The spring sales and advertising campaigns usually begin just as the race ends, in late January. A victory in the rally will boom the winner’s market share, both in France where the race has a tremendous following, and in the rest of Europe.

BMW knows how important ParisDakar is. French rider Hubert Auriol won the rally in 1981 and ’83 aboard a BMW, and the wins helped spice up the German company’s somewhat stodgy public image while enhancing their flat Twin’s reputation for reliability. And beating the combined efforts of the two Japanese giants probably didn’t hurt morale back at the home office, either.

Auriol was back on the team again this year, as was retired three-time 125cc World Motocross Champion Gaston Rahier from Belgium. Backing them up was a BMW support team of trucks, cars and an airplane, all of which helped swell the price tag for BMW’s Paris-Dakar venture to a reported $350,000. In the end, the expenditure of money, time and effort was worth it, as Rahier and Auriol finished first and second respectively, and BMW wrapped up the team title for the sixth year in a row. Hondas finished in third and fourth, while the highest placing Yamaha was sixth.

The ironic thing here is that the BMW, with its 60-year-old engine design that the factory is phasing out, is much better suited to the demands of the Paris-to-Dakar Rally than are the newwave Singles from Japan. The BMW has an engine that displaces about lOOOcc while the Singles are in the 600cc range, allowing the BMW a higher top speed. The configuration of the flat Twin engine also helps. Why? A big gas tank is a must for the rally; a 500-mile range is considered a necessity. Even with its huge 12-gal. capacity, the BMW has a lower center of gravity than the Honda and Yamaha Singles, thanks to its engine’s layout. The Singles also had monster gas tanks but the weight of the gas was carried higher because of their taller engines.

To offset their higher center of gravity and displacement handicap, the Singles weighed less and were more nimble through the low-speed rocky sections. Unfortunately for Honda and Yamaha, unforeseen circumstances forced event organizers to throw out a lot of the tight sections, the very places where they had hoped to catch up with the faster BM Ws. Political problems in Algeria and elsewhere caused Thierry Sabine, the exrally driver who dreamt up the Paris-toDakar Rally, into making some drastic changes to the course layout, even after the race had begun. The changes were favorable to the BMW team because they made the course a lot faster.

So, after just five days of racing, things looked pretty good for BMW, thanks to the fast sections. The Yamaha and Honda teams’ hopes began to fade as Rahier and Auriol continued to stretch their lead from minutes to hours. For three-time Paris-Dakar winner Neveu, the turn of events was particularly distressing. The way he saw it, a race of offroad riding skills had come down to a contest of whose machine had the highest top speed. “Honda should not come back here next year with a 600cc Single,” he muttered. “We need a lOOOcc Twin or something that will be able to beat the BMWs.”

For a while it looked as if BMW would record a 1-2-3 finish as French highway patrolman Raymond Loizeaux was running just behind the leading duo. The order was upset, however, when Loizeaux stopped to help Auriol solve a mechanical problem, in the process losing three hours that he never made up. Still, Loizeaux managed a fifth place and helped BMW secure the team trophy. Loizeaux’ position on the team has been debated in the past, but his assistance this year helped Auriol finish, and last year he did the same for Auriol’s win. A good team player. Besides, the French highway patrol (the Gendarmerie Nationale) places large orders with BMW, and Loizeaux’ inclusion on the team is a nice gesture as well as being good public relations.

At the halfway point, Auriol and Rahier had things so much in control that they took the time to engage in some intra-team politics. The BMW team claimed that there were no team orders for the race just to win—but to observers it looked as if mechanics were lavishing a little more attention on Auriol’s machine. And in fact a win by the Frenchman would have been more popular in France and Germany. There was the PR aspect; Auriol being handsome and tall. . .

Anyway, Rahier decided to put his foot down and voiced his displeasure to the mechanics. And the press and the TV people and anybody else who would listen. Some changes were promptly made.

Not that Rahier or his bike really needed the extra attention. He used his motocross experience to stay in front in the rough sections of the Ivory Coast and Guinea. He let Auriol get ahead for a short while but kept him just in sight. When the race ended on the beach at Dakar, Rahier was once again in the lead, 20 minutes ahead of Auriol and more than three hours in front of any body else.

The question that goes begging here, of course, is how an American would do in the Paris-Dakar. Some of our southwest desert racers certainly have the skill needed to go fast over unfamiliar terrain, albeit the 7000-mile length would be a challenge. Perhaps next year we'll get a chance to find out because there was an interested spectator at this year’s rally. Some guy by the name of Malcolm Smith, who has a little experience in offroad races. He was there as an observer with the Jeep people to see about the possibilities of an American entry in the car division for 1985. But if we know Malcolm, he’s already talking to some of his desert-riding friends.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMy Farewell Address

May 1984 By Allan Girdler -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

May 1984 -

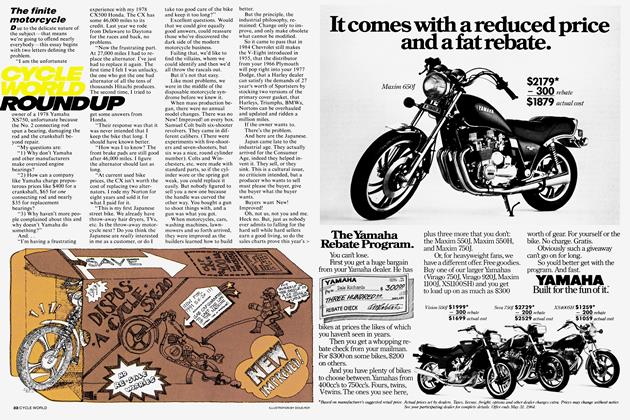

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Round Up

May 1984 -

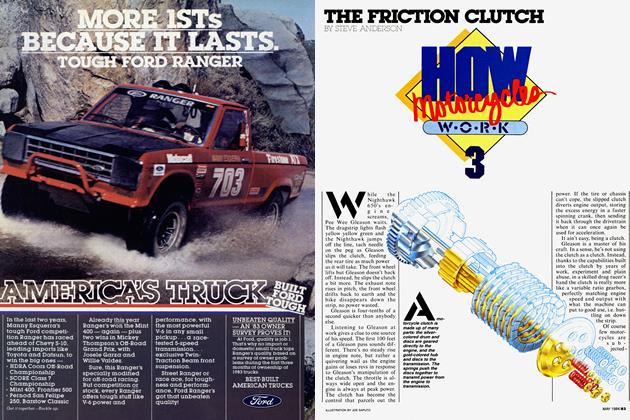

The Friction Clutch

The Friction ClutchHow Motorcycles Work 3

May 1984 By Steve Anderson -

Competition

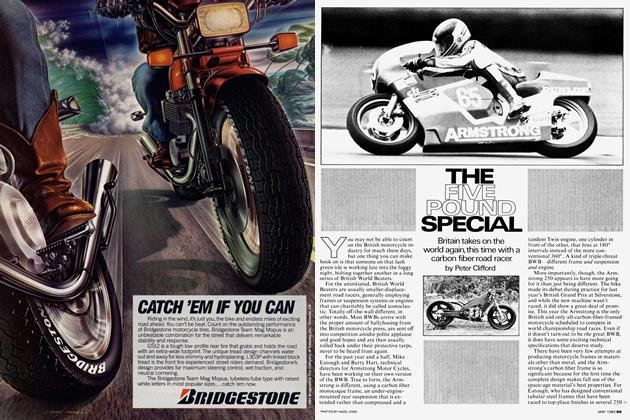

CompetitionThe Five Pound Special

May 1984 By Peter Clifford -

Competition

CompetitionOne Bike Fits All

May 1984 By Allan Girdler