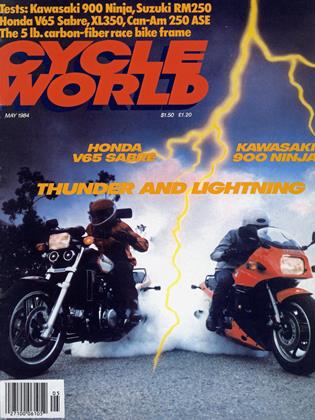

CYCLE WORLD ROUND UP

The finite motorcycle

Due to the delicate nature of the subject-that means we're going to offend nearly everybody-this essay begins with two letters defining the problem.

"I am the unfortunate owner of a 1978 Yamaha XS750, unfortunate because the No. 2 connecting rod spun a bearing, damaging the rod and the crankshaft beyond repair.

"My questions are: "1) Why don't Yamaha and other manufacturers make oversized engine bearings?

"2) How can a company like Yamaha charge prepos terous prices like $400 for a crankshaft, $65 for one connecting rod and nearly $35 for replacement bearings?

"3) Why haven't more peo pie complained about this and why doesn't Yamaha do something?" And... "I'm having a frustrating experience with my 1978 CX500 Honda. The CX has some 46,000 miles to its credit. Last year we rode from Delaware to Daytona for the races and back, no problems.

"Now the frustrating part. At 27,000 miles I had to re place the alternator. I've just had to replace it again. The first time I felt I was unlucky, the one who got the one bad alternator of all the tens of thousands Hitachi produces. The second time, I tried to

get some answers from Honda.

“Their response was that it was never intended that I keep the bike that long. I should have known better.

“How was I to know? The front brake pads are still good after 46,000 miles. I figure the alternator should last as long.

“At current used bike prices, the CX isn’t worth the cost of replacing two alternators. I rode my Norton for eight years and sold it for what I paid for it.

“This is my first Japanese street bike. We already have throw-away hair dryers, TVs, etc. Is the throw-away motorcycle next? Do you think the Japanese are really interested in me as a customer, or do I take too good care of the bike and keep it too long?”

Excellent questions. Would that we could give equally good answers, could reassure those who’ve discovered the dark side of the modern motorcycle business.

Failing that, we’d like to find the villains, whom we could identify and then we’d all throw the rascals out.

But it’s not that easy.

Like most problems, we were in the middle of the disposable motorcycle syndrome before we knew it.

When mass production began, there were no annual model changes. There was no New! Improved! on every box. Samuel Colt built six-shooter revolvers. They came in different calibers. (There were experiments with five-shooters and seven-shooters, but six was a nice, round cylinder number). Colts and Winchesters, etc. were made with standard parts, so if the cylinder wore or the spring got weak, you could replace it easily. But nobody figured to sell you a new one because the handle was curved the other way. You bought a gun to shoot things with, and a gun was what you got.

When motorcycles, cars, washing machines, lawnmowers and so forth arrived, they were improved as the builders learned how to build better.

But the principle, the industrial philosophy, remained: Change only to improve, and only make obsolete what cannot be modified.

So it came to pass that in 1984 Chevrolet still makes the V-Eight introduced in 1955, that the distributor from your 1966 Plymouth will pop right into your 1977 Dodge, that a Harley dealer can satisfy the demands of 27 year’s worth of Sportsters by stocking two versions of the primary cover gasket, that Harleys, Triumphs, BMWs, Nortons can be overhauled and updated and ridden a million miles.

If the owner wants to.

There’s the problem.

And here are the Japanese.

Japan came late to the industrial age. They actually arrived for the Consumer Age, indeed they helped invent it. They sell, or they sink. This is a cultural issue, no criticism intended, but a producer who wants to sell must please the buyer, give the buyer what the buyer wants.

Buyers want New! Improved!

Oh, not us, not you and me. Heck no. But, just as nobody ever admits to falling for the hard sell while hard sellers earn a good living, so do the sales charts prove this year’s whatever outsells last year’s whatever.

The Big Four have perfected production. They can design for a predictable service life. They can tool up for a specific production run. They needn’t re-tool, or crank out extras for spare parts because they won’t need piles of

spare parts because by the time the big items, like crankshafts, are needed, the entire machine will have been replaced by something new and different.

It’s good business. It’s fair. The buyer of the new motorcycle gets a quality product, good service for the money.

This is a good place to destroy another myth: There is no law requiring any manufacturer to stock parts for any length of time. The only law at work here is the law of supply and demand. If 17,000 people demand crankshafts for the Yamaha Triple or alternators for the Honda VTwin, somebody will supply them. If 17 people are the total demand, the supply will be what’s in the secondhand store.

So. We have not yet got the disposable motorcycle. Instead we have the finite motorcycle, a machine built 10 give good service to its first owner. Yes, the manufacturers care about you, the buyer. No, they don’t expect you to keep the bike forever. They think you’ll want a new and different bike next year.

If they’re wrong, then BMW was wrong to come out with the new Four that isn’t like all those years of Twins, and Harley was wrong to design new and better clutches that don’t easily fit in the older models, and Yamaha was wrong to suspend production of the 650 Twin after 13 years.

They think they’re right. They think exciting new designs will sell more bikes.

The majority rules.

And motorcycle enthusiasts get what they’re willing to pay for, which is another way of saying we get what we deserve.

The supreme Triumph?

“For man, as for flower and beast and bird, the supreme triumph is to be most vividly, most perfectly alive,” wrote English author David Herbert Lawrence in 1931.

To that list, let’s add motorcycles because it looks as if the Triumph motorcycle, given up for dead some months ago, is about to make a return to American shores.

As reported in the March Roundup, when the debtplagued Meriden factory went into receivership, English millionaire John Bloor purchased the Triumph name and manufacturing rights for five years. Bloor, who is primarily interested in developing the 900cc watercooled Diana engine that was in the testing stages before Triumph went bankrupt, then leased the name and manufacturing rights for the Triumph Twins to Racing Spares, England’s largest company dealing in parts for British motorcycles.

Racing Spares is owned by Les Harris, a man the flagwaving British press is calling “Triumph's millionaire saviour.” With his company’s 20 years of experience in building parts and the addition of some new expensive machinery for manufacturing frames and crankcases, Harris expects to turn out 20 to 25 motorcycles a week starting in June of this year.

The first models to go into production will be kick-start T140 Bonnevilles with improvements. Harris plans to use alloy cylinders with Nikasil linings that will save weight and decrease noise.

Brembo disc brakes will handle the braking chores and attach to fork leg bottoms of Italian manufacture. Rear shock absorbers will also be improved. “Quality is going to be the most important thing of all,” Harris said.

“We won’t be releasing any bikes until everything is perfect.”

Enter John Calicchio. Calicchio owns JRC, a southern California-based company that sells spare parts for—surprise—Triumphs. When Calicchio learned of the goings-on in England, he called Harris and told him he could sell as many bikes in the U.S. as he could get. The conversation led to Calicchio being named the sole U.S. distributor for the “new” Triumph motorcycles. (Domiracer, a parts company based in Cincinnati, Ohio, will be in charge of Triumph’s spare parts.)

Calicchio expects the first shipment of Triumphs to arrive by the end of August.

The bikes will be sold through the approximately 700 dealers already doing business with JRC. Calicchio is hoping to sell the bikes for under $3000, and says that advance orders for the Bonnevilles are “substantial.”

Will the Buffalo roam?

A company on the outskirts of Buffalo, New York, is proceeding with plans to design and sell an all-new line of Made-in-America bikes. Appropriately enough, the bikes are to be called Buffalos.

Buffalo Motorcycle Works which boasts 38 stockholders,

is developing a range of mod els, including Singles, VTwins and W-Threes (think of a 90-degree V-Twin having an extra cylinder in the middle) with displacements from 500 to I500cc. Originally an I800cc W-Three was planned, but problems with product liability insurance have since caused Buffalo’s design team to start thinking of a smaller Three, a company spokesman said.

Lawrence Domon, Buffalo Motorcycle president, said engineers already are testing two prototype Singles, a 650 and a 1000, and a V-Twin. When production begins, Domon hopes to have three Singles in the lineup, a 500, a 750,and a 1000,five VTwins, ranging from 500cc to 1500cc, and two W-Threes of as-yet-undetermined displacement. The Singles and W-Threes, said Domon, will be offered in custom/cruiser models and sport models, while the VTwins will come in custom/cruiser, sport and touring versions. Then there’s something the company is calling its “100-year machine,” a bike that designers propose to build almost exclusively from aluminum, stainless steel and bronze.

“No paint to chip, no rust. We're thinking of it as a lifetime bike,"Domon said.

According to Domon, the bikes’ most intersting technical feature will be the cylinder head design. “It’s such a simple design that it’s going to surprise a lot of people,” he said. “The cylinder heads will draw a lot of attention; they’re what make us different.” Another interesting feature of the engine is that > while designed to use overhead cams, it can be converted to use pushrods, should a purist buyer decide that’s what he wants.

If there are no hitches, Buffalo Motorcycles hopes to introduce its first V-Twin models in mid-year, Domon said.

“We're hoping to produce somewhere around 1000 bikes the first year. We’d like to keep production very small and quality very high,” he said.

Don't call 'em Maicos

Triumph isn’t the only motorcycle company on its way back from financial difficulties. Maico, under new ownership after bankruptcy troubles last year, is making motorcycles again and importing them to the U.S.

However, since Maico USA still has the rights to the Maico name in the U.S., the bikes are being imported as M Stars, said Ted Lapadakis of Hercules Distributing, the sole U.S. distributor of the bikes.

The first models brought in were the air-cooled 500 Super Cross and the liquid-cooled 250 Super Cross. Air-cooled 250 and 500 cross-country models will also be available, Lapadakis said.

M Star dealerships are being offered to shops that were selling Maicos before the bankruptcy, said Lapadakis. Other dealerships will be appointed later in the year.

Just add water

Over the past few years water-cooling has become a prerequisite in the 125 and 250cc classes in motocross competition. Last year, Husqvarna, the most traditional company in motocross, bit the liquid-cooled bullet and brought out radiator-equipped 125s and 250s. They’ve now taken things a step further with the 400WR, which the company is billing as the world's first open class, liquid-cooled production enduro motorcycle.

The bike is an ISDE replica, patterned after the machine that Swedish rider Sven-Erik Joensson rode to a gold medal and the overall individual victory in last year’s competition. Closer to home, Kevin Hines was aboard a 400WR when he won the opening round of the AMA national enduro series earlier this year.

The bike weighs a claimed 237 lb. and has a seat height of 37.8 in. Front wheel travel is 10.6 in. while the dualshock rear suspension works through 1 1.8 in. Husky claims the 400WR has better fuel economy and better power than last year’s aircooled 500. Suggested retail price is $3195.

When asked if Husqvarna would bring out a watercooled open class motocrosser this year, a company spokesman was properly evasive, saying, “That’s still a secret.” He did mention, however, that Husky is definitely experimenting with a single-shock motocrosser in Europe.

New faces

Cycle World welcomes aboard two new editorial staff members with this issue; Art Director Elaine Anderson and Feature Editor David Edwards. Elaine takes over from Barbara Goss, who went to San Diego to do design work for one of our consultants. David takes the place of Wade Roberts, who left CW for the hustle-bustle of a daily newspaper in Los Angeles.

Elaine comes to Cycle World after logging time in the art departments of Inside Sports, the ski magazine Powder and Flowers&, a trade journal for florists. Her involvement with motorcycles is long, if not particularly awe inspiring, starting with the times she and a boyfriend would quietly push her brother’s Yamaha Big Bear scrambler down the driveway and off into the night for clandestine rides around Pasadena, California. Great fun, she says, until they came home late one night to find the whole house up and waiting.

David joins Cycle World after a year as one of the editors at the weekly motorcycle.newspaper Cycle News. Prior to that, he was working as a photographer and finishing up his college education in north Texas. You may have seen David’s byline in this magazine before. He provided the photographic coverage of the Houston Astrodome Camel Pro Series openers in 1982 and ’83 and penned an article on helmet wind noise that we ran last year. His personal stable of motorcycles includes two sport bikes, a dual-purpose bike, an enduro bike, a trials bike and two BSAs—a Gold Star and a Victor the disassembled parts of which are currently accruing value on the shelves of his parents’ garage in Texas.

New features

Bqsides new names on the masthead, we’ve added two new features to Cycle World's pages.

Follow Up, which first ran in the March issue, will detail what happens good or bad —to test bikes that we keep around after their test period is over. We’ll also tell you how we liked/disliked certain accessories and occasionally include tips on how to make things work better. A catch-all section, in other words. Follow Up will run irregularly, whenever we have enough information to be useful.

The second new section, Things To Do, starts this month. In it you’ll find a rundown of, well, things to do with your street bike. Everything from Sunday morning rides to rallies to antique shows to club news will be highlighted in the section. If you’re a road rider looking for something to do, or belong to an organization scheduling an event, take a look at Things To Do.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

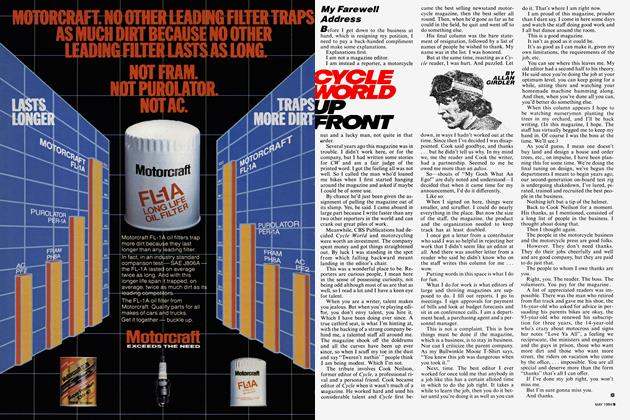

Up Front

Up FrontMy Farewell Address

May 1984 By Allan Girdler -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

May 1984 -

Features

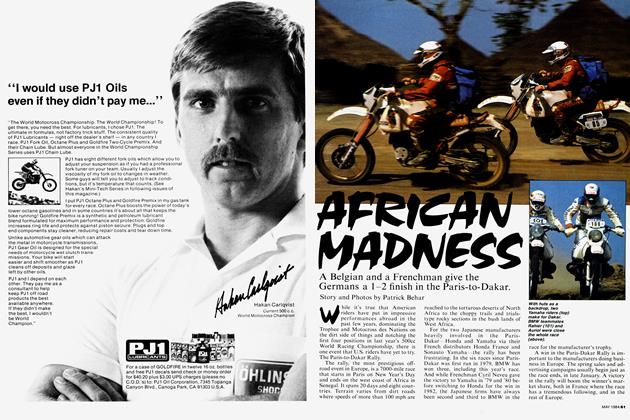

FeaturesAfrican Madness

May 1984 By Patrick Behar -

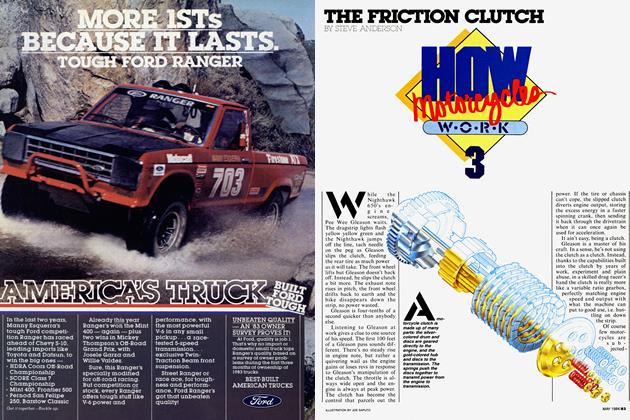

The Friction Clutch

The Friction ClutchHow Motorcycles Work 3

May 1984 By Steve Anderson -

Competition

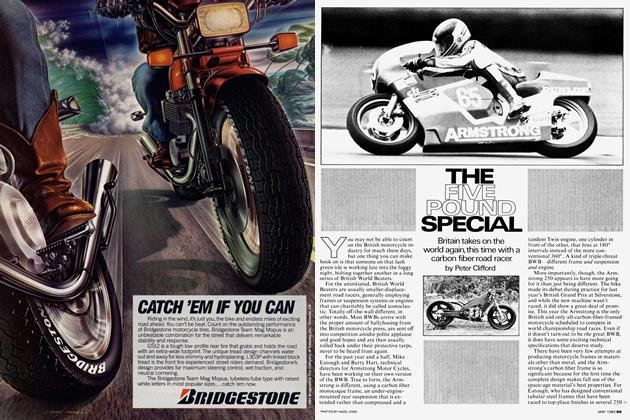

CompetitionThe Five Pound Special

May 1984 By Peter Clifford -

Competition

CompetitionOne Bike Fits All

May 1984 By Allan Girdler