ONE BIKE FITS ALL

The season begins with a revolution in machines, while rider rivalry takes up where it left off.

Allan Girdler

Every year the Camel Pro/AMA Grand National championship begins with a doubleheader at the Houston Astrodome, and every year all interested parties say it's nothing but bonus points, that the results of the short track and TT races don't forecast anything about the rest of the year.

And so it may prove for 1984. But don't bet on it. Things were very different this year, while at the same time they were the same . . . except better.

The difference begins with the rules. For 1984 the pros are allowed to race short track with four-stroke Singles up to 500cc, as well as the 250 two-strokes that have been the machines for 10 years.

TT has allowed two-stroke Singles, and 600cc four-stroke Singles and 750 Twins for the same length of time. It's been an interesting era, in that moto cross-based Maicos, Hondas and Yamahas have been running against Honda and Yamaha four-stroke Singles and Twins from Harley, Yamaha, Tri umph, Norton and BSA. There have been fierce struggles, surprise winners and lots of fuel for bench racing.

When the new rules were announced they seemed puzzling. It wasn't as if no body knew where to find or how to build a competitive two-stroke. Officially the change was made to make things easier for the privateer, which cynics interpreted as meaning the factories had ex erted themselves. Politics as usual, in other words, but nothing beyond that.

All wrong. The four-strokes took over short track in one day. Only one two stroke, a Honda, made the main event. It was ridden by Terry Poovey, who won last year's short track aboard a Honda two-stroke and understandably didn't want to tamper with his formula.

The other racers had no such limita tions. Most teams brought a two-stroke and a four-stroke. They practiced, and all the two-strokes went back in the trucks.

The four-strokes were not only faster, they worked better.

They did that because in dirt track, power isn't everything. On packed, treated dirt, using the semi-knob tires the rules dictate, what matters is the power the bike will put on the ground. If the maximum is, say, 50 bhp, then a 50 bhp bike will beat the one with 45, and the one with 55.

It's easier to get 50 bhp from the 500 than the 250, and the power is milder, adjustable even. Both riders and tuners can make mistakes and be forgiven.

Further, the rules change encouraged development. The factory teams and the better independents have been working with the Singles from Honda and Yamaha and those made by Rotax for themselves, Can-Am, Harley-Davidson and KTM.

That brought experimentation, spe cifically in suspension. Most visible here is Gil Vallaincourt of Works Perfor mance, who last year designed a risingrate single rear shock for the Honda team. He's still working on that, and he~s come up with single shock on one side of the swing arm, as in BMW except it's nearly horizontal and angles in from the left side of the frame toward the rear hub. Most of the bikes in both short track and TT main events were using Vallaincourt's thinking.

Which includes longer travel. There's another revolution. Most of us naturally assume that lower is better for flat track, that you only need extra suspension for the jumps and bumps of TT. Vallaincourt says no, that suspension that's really right for one set of condi tions will be right, assuming minor tun ing, for others, and that the machine can be so low it slides out when it should be powering forward. (He also admits that not everybody believes that yet. )

Vallaincourt also says longer travel makes for bumpier tracks. Better suspension means better traction, the higher bike with extra grip transfers weight and the turns get rougher. That’s the way it worked in off-road racing, so it should be true here, too.

Further still, the racers say the Astrodome’s dirt is wearing out. Yes. Wearing out. Shoved in for the races, packed down, moved out, put back, watered, ground into mud, dried, whipped into dust, the dirt is reported to be losing its bounce.

What all this means, assuming Houston is a forecast, is closer competition.

Everybody can afford the same starting place, the 500 Single. There may have been more romance with the underdog Maico, the thundering Harley Twin and the traditional Triumph, but with all the good riders and tuners crafting within the same basic framework, there's more emphasis on who's got the skill and who can best predict the optimum gearing/ tune/tires.

Plus politics. Out early for the best qualifying short track time was Hank Scott, riding for Tex Peel, w ho used to be partners with Ricky Graham, who's now with Honda along with Bubba Shobert who signed just minutes before he would have gone with a Harley support deal, freeing that arrangement for Jimmy Filice. Just as in any extended family there are deep and lasting friendships, branch rivalries and cousins who haven't spoken for 20 years. This year's war is between the two factories, Harley and Honda (notice the use of alphabetical order). Harley refers to Honda as the best

team money can buy, while the Honda camp pointedly refers to the orange machines as Can-Ams.

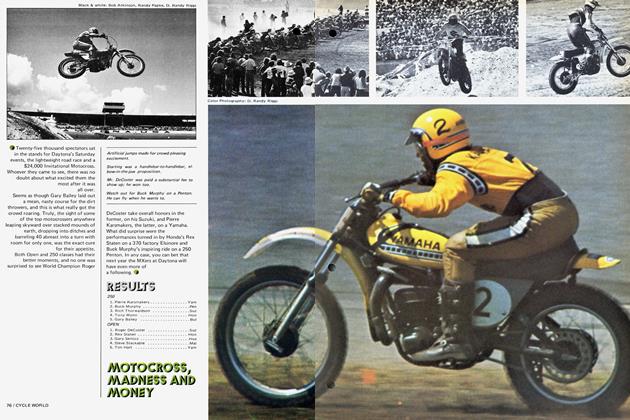

Racing. Not to destroy any suspense, but there were jokes about the plot to inspire National Champion Randy Goss. He won the 1983 title on consistency, earning points every time out, while rivals Ricky Graham and Jay Springsteen won more races. After Goss won the short track, reporters joked they only disparaged Goss' lack of total wins to get him mad, that is, faster.

Scott's fast time turned out to have been won by getting there early. By the time 80-odd riders had been out, the track was slick, loose and rough, all at the same time, and Scott went from pole position in the first heat to third, behind Rod Sullivan and Dan Bennett.

Goss showed his form in the second heat. He didn't qualify well, or start well, and second-year expert Pete Haines took the second heat, wire to wire.

Goss meanwhile worked his way into third, behind Bubba Shobert. He sat on Shobert's rear fender and watched.

Short track is an oval. Shobert was making his ow n oval, sort of a wider and misplaced one, by going wide and high for the start-finish straight, then tucking in tight on the back straight.

Goss, the thinker, reversed the pattern. He tucked in for the front half, swung wide for the back half and nailed Shobert, for second place and a sure spot in the main, on the last lap. Neat.

Two-stroke Terry Poovey won the third heat by shadowing Doug Chandler, 1983 rookie of the year, then getting inside so close Chandler snapped upright and lost that vital few feet. In the fourth heat Graham moved into second and came out of the last turn of the last lap right next to Ronnie Jones, so close that the officials called for instant replay at last, one good reason to race in football stadiums. (It looked like Graham to this reporter, but the camera said Jones.)

Then the last two heats went to Fran Brown and Jay Springsteen, more or less parades except that Springsteen's a treat to watch even by himself, and the last heats were the slow ones.

There was lots of thinking before the main event. The clocks tell part of the story; times for the heats were 2:25.9, 2:26.1. 2:24.2, 2:27.0, 2:27.2 and 2:27.5.

So the track was slowing down as it roughed up. The exception, the heat won by Poovey, proved that in the right hands, with no mistakes to overcome, the two-stroke can still win.

There were personal issues as well. Not personal in the grudge sense, but personal/professional. Graham and Shobert are now Honda factory riders. Fast year they were Harley support riders, so they'd like to prove they made the right choice. Filice filled the spot vacated by Shobert; he'd like to show he's worth the investment. Hank Scott gave Honda their first 750 Twin victory in Camel Pro and had hoped for a place on the payroll. Instead. Honda hired Chandler: That put Chandler in the spotlight while Pete Hames, who was expected to win the rookie title last year, looks forward to beating Chandler this year.

So they all worried about picking the best tire and gearing for the season's first race. For instance. Bill Werner loosened the front wheel on Springsteen's bike, then stared at it until he got up and put on a new back tire. Then he put on a new front tire.

The start was stopped when one man jumped the light. Three laps into the sec-

ond try, Mickey Fay, Randy Green and Chandler tangled and the race was stopped while Fay was taken away for inspection. (He was shaken up. He crashed three times this weekend, hard but not serious, and later quipped he’d been getting the season’s tumbles taken care of early.)

Springsteen took advantage of the inuption to zip over to the pit gate and have the old front tire put back on. The final re-start, so to speak, was single file with Hames in the lead, oss in the middle of the back. Charger Goss had seen something or figured something out. He zapped past Fran Brown, Graham, Springsteen and closed up on Hames. The two looked equal except that every time they powered out of the second and fourth turns, Goss's Harley had more jump than Hames’ Har. . . uh, excuse it, CanAm. Goss caught up, took the lead, lost it, got it back and motored away, riding with an intensity the younger Hames couldn’t match. Springsteen meanwhile did his best with less, in a comfortable but tractionless third. Graham’s first Honda ride netted fourth place.

Fater Goss was asked why his bike hooked up better than the others. “The traction was there,” he said, “you just had to know where to find it.”

Harley’s short track effort hasn't looked that good in years, while Honda

hasn't lost anything. Graham's their number one. Although he’s never done well on two-strokes, there’s nothing he likes better than a rough track, which Houston became. Two-stroke Terry Poovey meanwhile battled to eighth and Chandler versus Hames, remember was 1 2th.

The TT

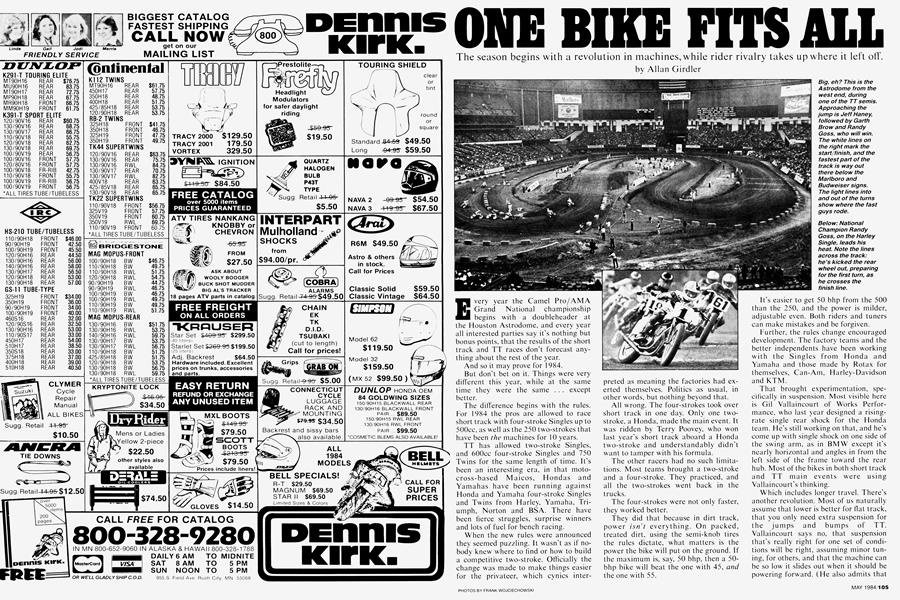

While the bikes grew 100 cc, the track was re-arranged for the traditional Uplus-jump. (See large photo with small bikes in it. Indoors at the Astrodome isn’t like indoors elsewhere.)

Fast qualifier was former national champ Steve Eklund, aboard an omnipresent Rotax, this time bearing the KTM label. Next came Graham, who won the TT here two years ago, then Pete Hames. Eklund, Goss and Fran Brown, also in the top 10 qualifiers, were in the first heat. Goss got past them both, then when he was in the clear, he fell. Just tipped over in the horseshoe. He got back up, in eighth, and made the final only by winning the first semi-final.

Pause for racing luck: In last year’s final race, Goss looked to be too far behind to make the main event, upon which hinged the title. But three guys in front of him fell, and he was home free. This spill evened things up.

When Goss dropped it, Mrs. Goss, herself a former champion ice racer and a member of a racing family, wasn’t upset. She’s seen it happen hundreds of times.

By contrast, when Jim Filice took a slam into the ground later in the evening, his fiance raced across the infield, scattering grown men like ten-pins, to be sure he was okay. When she was sure he was, she got mad. When she saw his arm was hurt, she got worried. Next morning, though, both were smiling again. The wedding is still on.

Speaking of full circles, two years ago Springsteen won the short track on his ancient Aermacchi. Last year the bike died of exhaustion. So this year there are brand new machines and Springer was all set for his TT heat when the clutch quit. New may be better than old, but new also means another set of weak links to discover and reforge.

Back to the heats. In the second, more jumpers caused more re-starts. Poovey— on a four-stroke. No sense being impractical—got the lead but fell. Rich Arnaiz won, with Graham, one of the guilty prestarters, in second after a spectacular charge. Hames took the fourth heat, the one in which Springsteen’s clutch quit.

The come-from-behind trophy of the evening went to Harley teamster Scott Parker. He was trying too hard and overrode into a fourth in his heat. However, his determination was such that he snapped off a footpeg. Deprived of a place to stand, he took a calmer approach . . . and went faster. This was noted by his crew, who'd also seen what the bike was doing when Parker overcharged.

They replaced the peg and did other things too quickly for even the most zealous reporter to note. In the last-ditch, winner-into-the-main, Parker was magnificent. A treat to the eye, especially his sweep through the second turn, the fastest place on the track. He won, he made the national, and he deserved it.

Parker however started the main at the back. In the front at the start were Graham and Shobert, who swapped in a manner that proves teammates can still compete against each other. Shobert couldn't get the front tire to stick and Graham got clear. Eklund meanwhile came out of the middle and up to second. Both men have won the event before and both seemed to be using the same lines and styles, except that Graham had more drive off the turns. (Eklund said later his rear shock had faded, i.e. it wasn’t as willing to keep the rear tire engaged.) Shobert held on, Parker worked up to fifth but slipped to eighth, Hames was edged out of fourth by Goss, who started on the back row and did a businesslike run, getting one man at a time.

Graham had a good lead as he and Eklund caught the slower riders.

He also had, well, potential insurances

The insurance is named Ken Tolbert. He’s an apprentice, you might say. While earning his expert rider’s license, Tolbert has been working for Tex Peel. Last season he was Graham’s mechanic, friend and play-riding companion while learning the tuning arts from Peel and Ron Alexander.

This year, Tolbert qualified for the national, his first. And an achievement: the 48 fastest in time trials run the qualifiers, and only the best 15 of the 48 make the national.

There Tolbert was, in 12th, when his pal passed him. The flag fell before Eklund caught Tolbert, so how wide Tolbert’s bike would have been had Eklund been catching Graham, we can only guess.

At said flag it was Graham, Eklund, Shobert and Goss. (Take notes.) Sophomores Chandler and Harnes were fifth and eighth, a switch on their short track results.

The track was fast, with a fair groove and a useful cushion on the outside of the turns. Graham said he could have won the race with his old bike, that is, the Harley XR750, which brought hoots and cries of “Speak into the microphone” from the assembled press.

Graham meant no disloyalty and was telling the truth as he saw it. Of course, Graham’s the only rider in the Houston TT’s 16-year history to win on a Harley 750 so he probably was speaking for himself only.

The inevitable downside is that the top racers won’t be seen everywhere. Harley doesn’t mind using ideas not invented there. One of their engineers has the rights to a promising road-race 750, a two-stroke of all things, and they’d hoped to appear in the road-race portion of the national championship. But they don’t have the money.

Honda has the money and the Formula One machines. But despite Honda’s desire to win the AMA title, the one prize in racing Honda hasn’t won, there are no plans to field Graham, Shobert or Chandler in road races. The trio is interested, has been to Keith Code’s racing school, where Chandler showed such promise Code would like to sponsor him. But Honda says no, reason not given.

Aside from that . . . the 1984 season looks better than promising. Thanks to their finishes of l-4 and 4-1 in the first two races Goss and Graham, Harley and Honda, are tied for the series lead. Things could change; Springsteen is in bouncing good health. And Houston doesn’t mean anything.

Which is where we came in. Except that anybody looking for a real bargai in used racing equipment might ch the prices on a 250 short-tracker or a TT bike.

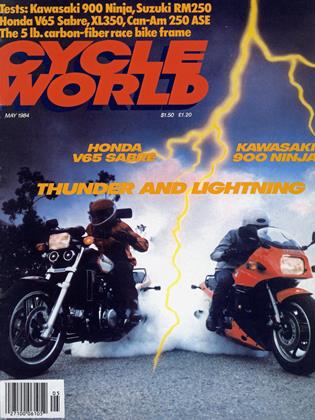

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMy Farewell Address

May 1984 By Allan Girdler -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

May 1984 -

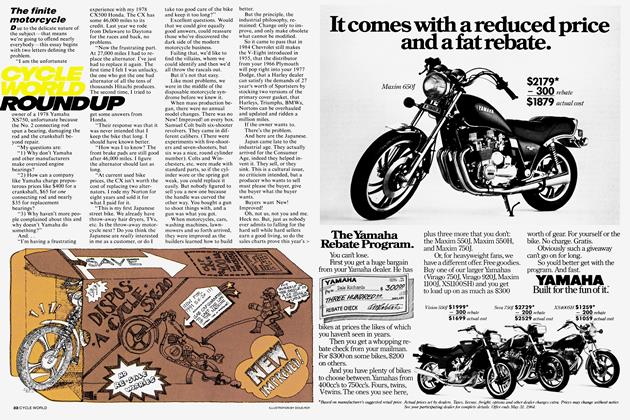

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Round Up

May 1984 -

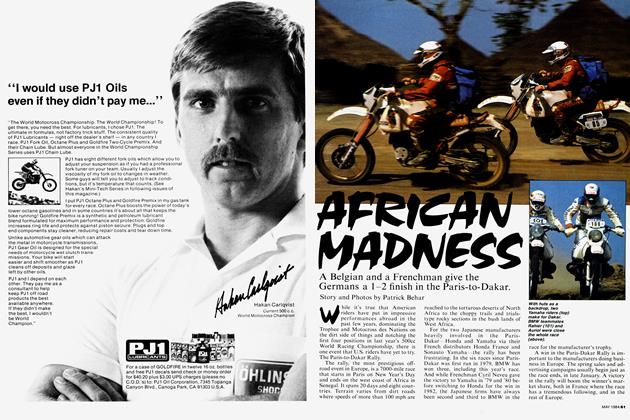

Features

FeaturesAfrican Madness

May 1984 By Patrick Behar -

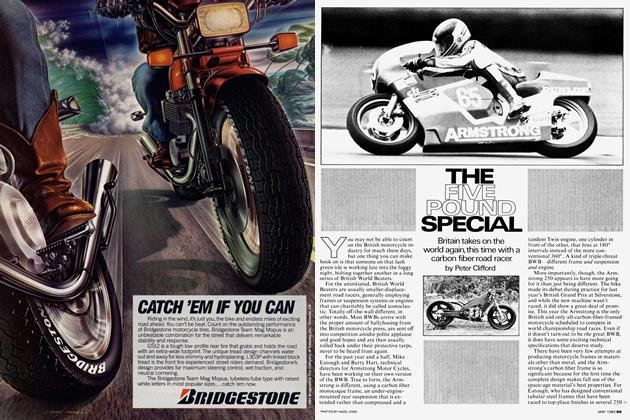

The Friction Clutch

The Friction ClutchHow Motorcycles Work 3

May 1984 By Steve Anderson -

Competition

CompetitionThe Five Pound Special

May 1984 By Peter Clifford