ANATOMY OF A CLAIM

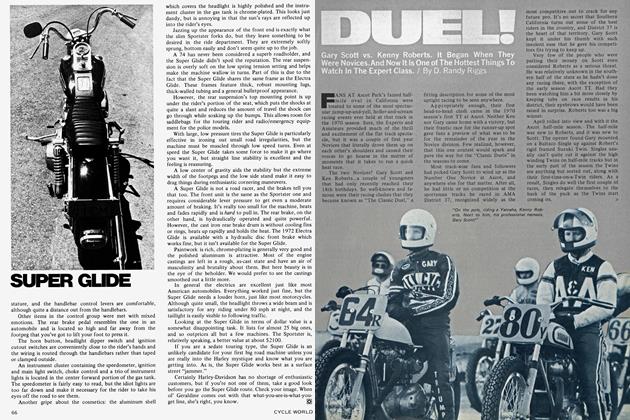

Rumors Have Floated Around Since May That Kenny Roberts’ OW72 Yamaha Would Be Claimed. At The First Of Two Indy Mile Nationals, Rumor Was Transformed Into Fact.

D. Randy Riggs

AS MIKE KIDD, Jay Springsteen and Rex Beauchamp were showing their pearly whites in the winners' circle of the Saturday night Indy Mile National, a lesser known rider by the name of Sam Ingram was searching out Central Regional AMA referee Duke Oliges, and he had the fat sum of $3500 in his hip pocket. For those of you who don't know it, $3500 is a magic number around the Class C dirt circles these days. That number of bucks, and adherence to a few other requirements outlined under the AMA's infamous claiming rule, will get you the power-producing components of a fellow competitor's race bike if you're so inclined.

The other requirements are that you file your claim in writing within half an hour of an event's completion, and, most important, that you were entered in that event. Ingram met the requirements, had the money, and wanted the OW72 750cc Yamaha engine nestled in machine No. 2 belonging to Yamaha International Corp. It had been ridden only minutes before by Kenny Roberts to a not-too-impressive 7th-place finish in the first of the two Nationals.

The claiming rule had lately raised its head in surprising fashion when National Champion Gary Scott claimed the factory H-D that Rex Beauchamp had used to win the San Jose Mile. Gary plucked the machine from the very company from which he had severed relations over the winter under some rather hostile conditions. That claim had probably been the most astounding since the AMA had conceived the idea in 1971 in an effort to keep factory-produced megabuck exotica from completely trashing the hopes of privateers. Taken in that spirit, the claiming rule is a good one, but why, then, has each and every claim produced nothing but hostility and created a pile of extra work for people who are already doing their share of overtime?

Factory-employed mechanics are no different from the wrenches building Harry Local's 750 Whatzit in the back room of a dealership, or in the family garage, for that matter. Each puts his heart and soul into the work at hand, calling on every past bit of experience in an effort to create the very best package he can for his rider. Granted, the factory man usually has a dyno room at his elbow, money to spend, and more experience to call on should he run into a problem. But who is silly enough to be-

lieve that all factory wrenches started out as factory wrenches?

They are there because they've paid their dues . . . the rewards for which are dyno rooms, full toolboxes, factory support and a budget. And, oh yes, a rider who deserves their efforts as much as they deserve his. And yet their efforts and hard work can be snatched away in an instant under the guise of the claiming rule, usually by someone who can make as much use of the package as a giraffe can a backyard doghouse.

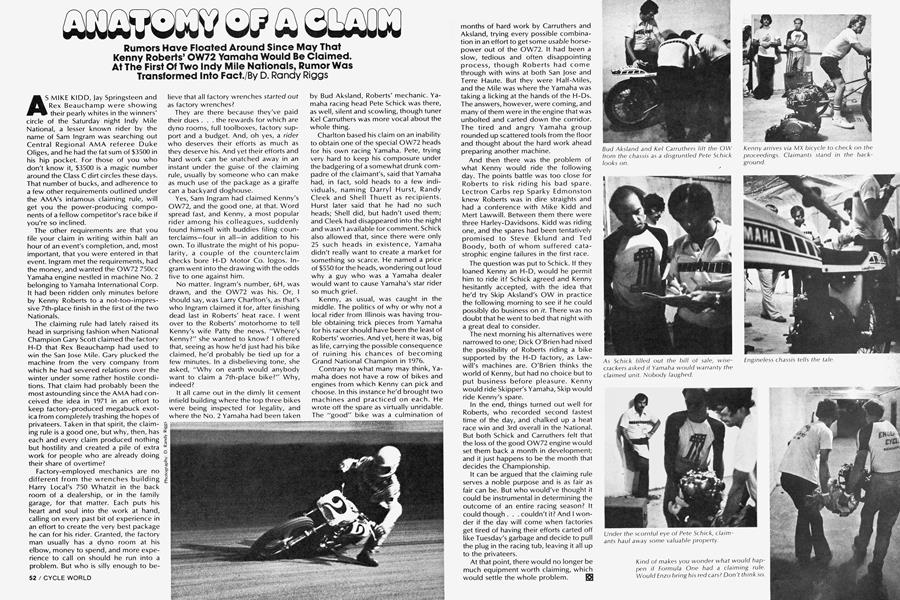

Yes, Sam Ingram had claimed Kenny's OW72, and the good one, at that. Word spread fast, and Kenny, a most popular rider among his colleagues, suddenly found himself with buddies filing counterclaims—four in all-in addition to his own. To illustrate the might of his popularity, a couple of the counterclaim checks bore H-D Motor Co. logos. Ingram went into the drawing with the odds five to one against him.

No matter. Ingram's number, 6H, was drawn, and the OW72 was his. Or, I should say, was Larry Charlton's, as that's who Ingram claimed it for, after finishing dead last in Roberts' heat race. I went over to the Roberts' motorhome to tell Kenny's wife Patty the news. “Where's Kenny?" she wanted to know? I offered that, seeing as how he'd Just had his bike claimed, he'd probably be tied up for a few minutes. In a disbelieving tone, she asked, “Why on earth would anybody want to claim a 7th-place bike?" Why, indeed?

It all came out in the dimly lit cement infield building where the top three bikes were being inspected for legality, and where the No. 2 Yamaha had been taken

by Bud Aksland, Roberts' mechanic. Yamaha racing head Pete Schick was there, as well, silent and scowling, though tuner Kei Carruthers was more vocal about the whole thing.

Charlton based his claim on an inability to obtain one of the special OW72 heads for his own racing Yamaha. Pete, trying very hard to keep his composure under the badgering of a somewhat drunk compadre of the claimant's, said that Yamaha had, in fact, sold heads to a few individuals, naming Darryl Hurst, Randy Cleek and Shell Thuett as recipients. Hurst later said that he had no such heads; Shell did, but hadn't used them; and Cleek had disappeared into the night and wasn't available for comment. Schick also allowed that, since there were only 25 such heads in existence, Yamaha didn't really want to create a market for something so scarce. He named a price of $550 for the heads, wondering out loud why a guy who was a Yamaha dealer would want to cause Yamaha's star rider so much grief.

Kenny, as usual, was caught in the middle. The politics of why or why not a local rider from Illinois was having trouble obtaining trick pieces from Yamaha for his racer should have been the least of Roberts' worries. And yet, here it was, big as life, carrying the possible consequence of ruining his chances of becoming Grand National Champion in 1976.

Contrary to what many may think, Yamaha does not have a row of bikes and engines from which Kenny can pick and choose. In this instance he'd brought two machines and practiced on each. He wrote off the spare as virtually unridable. The “good" bike was a culmination of months of hard work by Carruthers and Aksland, trying every possible combination in an effort to get some usable horsepower out of the OW72. It had been a slow, tedious and often disappointing process, though Roberts had come through with wins at both San Jose and Terre Haute. But they were Half-Miles, and the Mile was where the Yamaha was taking a licking at the hands of the H-Ds. The answers, however, were coming, and many of them were in the engine that was unbolted and carted down the corridor. The tired and angry Yamaha group rounded up scattered tools from the floor and thought about the hard work ahead preparing another machine.

And then there was the problem of what Kenny would ride the following day. The points battle was too close for Roberts to risk riding his bad spare. Lectron Carbs rep Sparky Edmonston knew Roberts was in dire straights and had a conference with Mike Kidd and Mert Lawwill. Between them there were three Harley-Davidsons. Kidd was riding one, and the spares had been tentatively promised to Steve Eklund and Ted Boody, both of whom suffered catastrophic engine failures in the first race.

The question was put to Schick. If they loaned Kenny an H-D, would he permit him to ride it? Schick agreed and Kenny hesitantly accepted, with the idea that he'd try Skip Aksland's OW in practice the following morning to see if he could possibly do business on it. There was no doubt that he went to bed that night with a great deal to consider.

The next morning his alternatives were narrowed to one; Dick O'Brien had nixed the possibility of Roberts riding a bike supported by the H-D factory, as Lawwill's machines are. O'Brien thinks the world of Kenny, but had no choice but to put business before pleasure. Kenny would ride Skipper's Yamaha, Skip would ride Kenny's spare.

In the end, things turned out well for Roberts, who recorded second fastest time of the day, and chalked up a heat race win and 3rd overall in the National. But both Schick and Carruthers felt that the loss of the good OW72 engine would set them back a month in development; and it just happens to be the month that decides the Championship.

It can be argued that the claiming rule serves a noble purpose and is as fair as fair can be. But who would've thought it could be instrumental in determining the outcome of an entire racing season? It could though . . . couldn't it? And I wonder if the day will come when factories get tired of having their efforts carted off like Tuesday's garbage and decide to pull the plug in the racing tub, leaving it all up to the privateers.

At that point, there would no longer be much equipment worth claiming, which would settle the whole problem. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

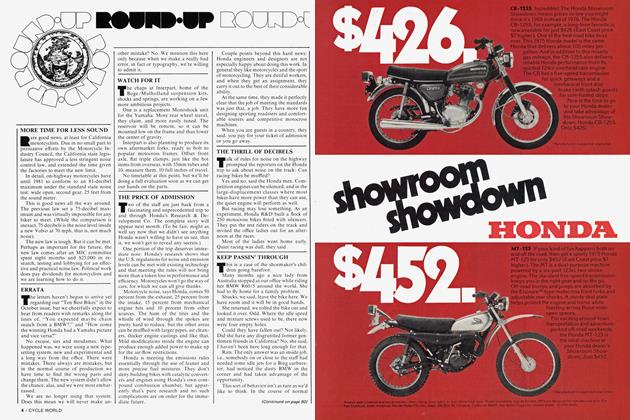

DepartmentsRound·up

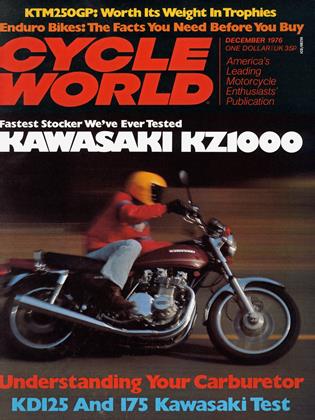

December 1976 -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1976 -

Demise of the British Industry, Ii

December 1976 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

December 1976 -

Technical

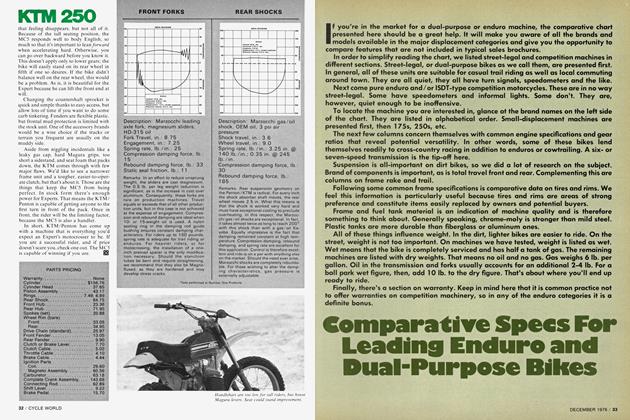

TechnicalComparative Specs For Leading Enduro And Dual-Purpose Bikes

December 1976 -

Features

FeaturesPro Techniques For Off-Road Riding

December 1976 By Russ Darnell