WHY THE FUTURE ISN’T MY SECRET

UP FRONT

Allan Girdler

Due to a childhood spent in a small New England town with a skinflint school board. I don't believe in prophets or in people who do.

In the land of Waste Not, Want Not, skinflint isn't an insult. What the school people did, when I was young, was figure that textbooks were useful until they wore out, that is, when the pages crumbled. The contents themselves were assumed to be permanent. So it happened that when I was in grade school, after WW2, I read books from before WW2.

And lost my faith in prophecy. No problem with the discovery of America or such, but when I read in Social Studies about the future, the books told me that within a few years we’d be riding about in the airplanes sure to live in every garage. We’d have little plastic cars with bubble roofs. Not too many of us, though, because the declining birth rate meant the population would have to live a long time or grass would grow in the streets.

None of the above—especially the last, speaking of curing a problem—came to pass. Instead, by the time I read these predictions, we had had a large war and gone on to radar, atomic energy and television. Far more influential, that last, than any garage full of airplanes could have hoped to be.

More than hindsight is involved here. When I got old enough to wonder why the experts had so completely failed. I worked out two things.

One is that the experts are wrong more often than not.

The other is that prophets miss their marks because they predict the future from a base of the recent past.

Did the ownership of private airplanes grow by leaps between 1925 and 1935? Then it must grow equally between 1935

and 1945. Did the birthrate decline between 1930 and 1935? Then it must sink from sight by 1950. Radar and computers and most of all television had no immediate past, so they were left out of the future.

1 mention this because what with the new models, government regulations and cultural shocks of the present, seems to me I’ve been hearing a lot of predictions, mostly from people who. like the hapless seers of my childhood, think you can predict the future from the past, or who have faith in those who try it.

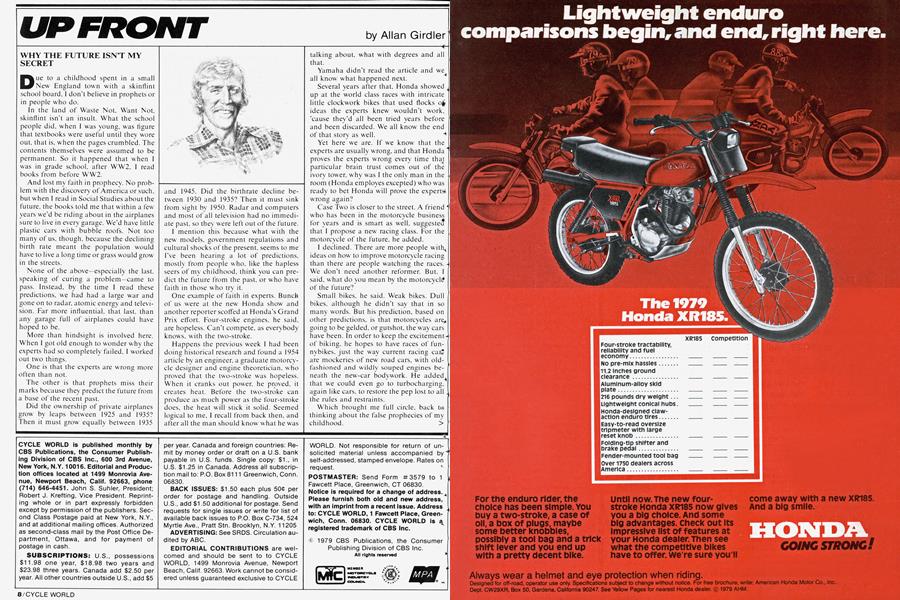

One example of faith in experts. Bunch of us were at the new Honda show and another reporter scoffed at Honda’s Grand Prix effort. Four-stroke engines, he said, are hopeless. Can’t compete, as everybody knows, with the two-stroke.

Happens the previous week I had been doing historical research and found a 1954 article by an engineer, a graduate motorcycle designer and engine theoretician, who proved that the two-stroke was hopeless. When it cranks out power, he proved, it creates heat. Before the two-stroke can produce as much power as the four-stroke does, the heat will stick it solid. Seemed logical to me, I recall from back then, and after all the man should know what he was talking about, what with degrees and all that.

Yamaha didn’t read the article and we all know what happened next. Several years after that, Honda showed up at the world class races with intricate little clockwork bikes that used flocks o£ ideas the experts knew wouldn’t work, ’cause they’d all been tried years before and been discarded. We all know the end of that story as well. ^

Yet here we are. If we know that the experts are usually wrong, and that Honda proves the experts wrong every time thaj particular brain trust comes out of the ivory tower, why was I the only man in the room (Honda employes excepted) who was ready to bet Honda will prove the expert» wrong again?

Case Two is closer to the street. A friend who has been in the motorcycle business for years and is smart as well, suggested that I propose a new racing class. For the motorcycle of the future, he added.

I declined. There are more people withA ideas on how to improve motorcycle racing than there are people watching the races. -We don’t need another reformer. But. I said, what do you mean by the motorcycle of the future?

Small bikes, he said. Weak bikes. Dull bikes, although he didn’t say that in so many words. But his prediction, based on other predictions, is that motorcycles are* going to be gelded, or gutshot, the way cars have been. In order to keep the excitement ^ of biking, he hopes to have races of funnybikes, just the way current racing cari are mockeries of new road cars, with oldfashioned and wildly souped engines beneath the new-car bodywork. He added^ that we could even go to turbocharging, again like cars, to restore the pep lost to all the rules and restraints.

Which brought me full circle, back te thinking about the false prophecies of my childhood. >

Seems to me I’ve heard a lot of th#is lately. I keep being told that motorcycles are going to get so big that they do themselves in, like mastodons. At the same tirnp there are predictions that the safety wowsers will prevail. There will be no more* dirt bikes and road bikes will barely hit 55 mph whilst making the noise of an enragstd sewing machine.

What we have here I think is a view of the motorcycle’s future based on the motorcar’s recent past.

I don’t buy it. True, the sporting motor^ car has gone the way of the mastodon, and true, the car of today isn’t nearly as muqh fun as the car of yesterday.

This isn’t going to happen with us. WhaD happened to the car wasn’t the result of government intervention. That was tht symptom. There was no public clamor for safety. As Detroit learned the hard way, not* only does safety not sell, it can’t even Çe given away. As all the car companies learned an even harder way, their custom-ers didn’t like them. So when a few ambitious people took after the car, the publicapproved. Not because they clamored for air bags and massive bumpers, but because« buying a car is an exercise in humiliation. The only revenge the public could get wás letting Big Govt, bring Big Business to its knees.

We are not like that. When dealing with the cretins who sold my wife her car has driven me into hts of helpless rage, I vis# Greg and Dallas. They’ve just opened a Suzuki store. I don’t own a Suzuki, buf they are nice chaps and like bikes, so the place is a good one to hang around at. ás motorcycle stores have always been and car stores are not. When the government aims at the motorcycle, we take sides, bu^ it’s the side of truth and freedom, i.e. we defend ourselves and our bikes and the^ men who make and sell them.

Next, the men who make motorcycles are good at it. As we’ve seen recently, meeting noise and emissions rules does not mean inferior or slower or less excitine machines.

Some of the present trends will run their^ own courses. There’s a point at which the engine is too big, and the suspension travel too long. When that stage is reached, the problems will solve themselves.

For the rest, the only machines we’ve lost have been the big two-stroke road bikes. They went away not because of the law, but because the buyers didn’t buy1 them.

What we are going to get next, I don’t pretend to know. Not in detail, anyway. But, looking at how much better motorcycles have become, and how quickly thei?makers have responded to our wishes, 1 expect we’ll get whatever it is we want. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1979 -

Departments

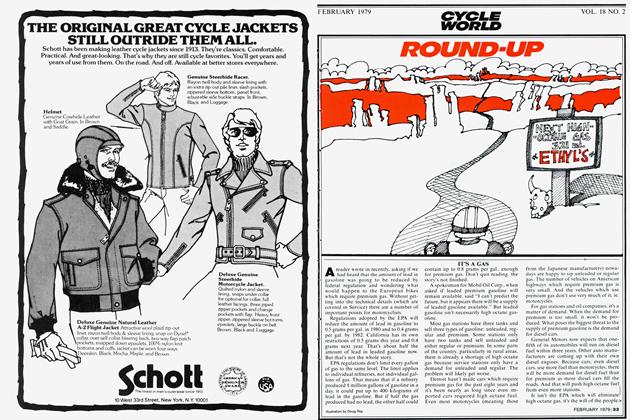

DepartmentsRound-Up

February 1979 -

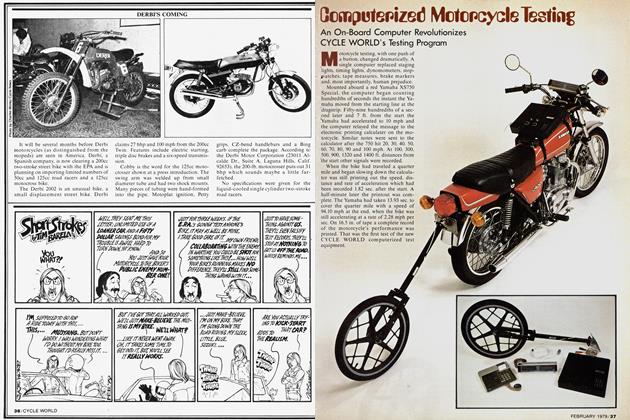

Short Strokes

February 1979 By Tim Barela -

Technical

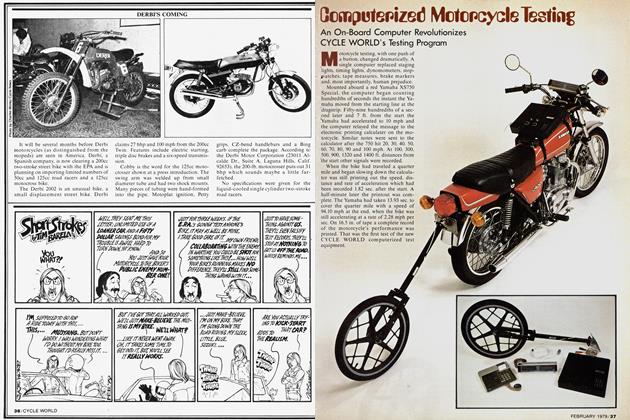

TechnicalComputerized Motorcycle Testing

February 1979 -

Features

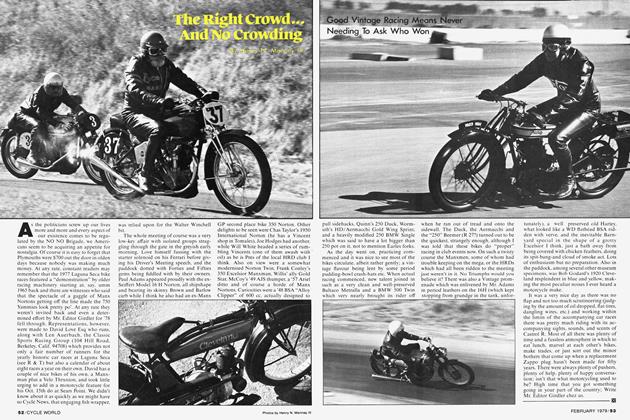

FeaturesThe Right Crowd... And No Crowding

February 1979 By Henry N. Manney III -

Features

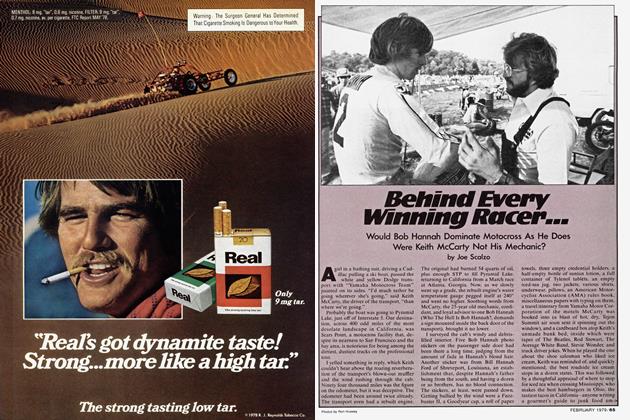

FeaturesBehind Every Winning Racer...

February 1979 By Joe Scalzo