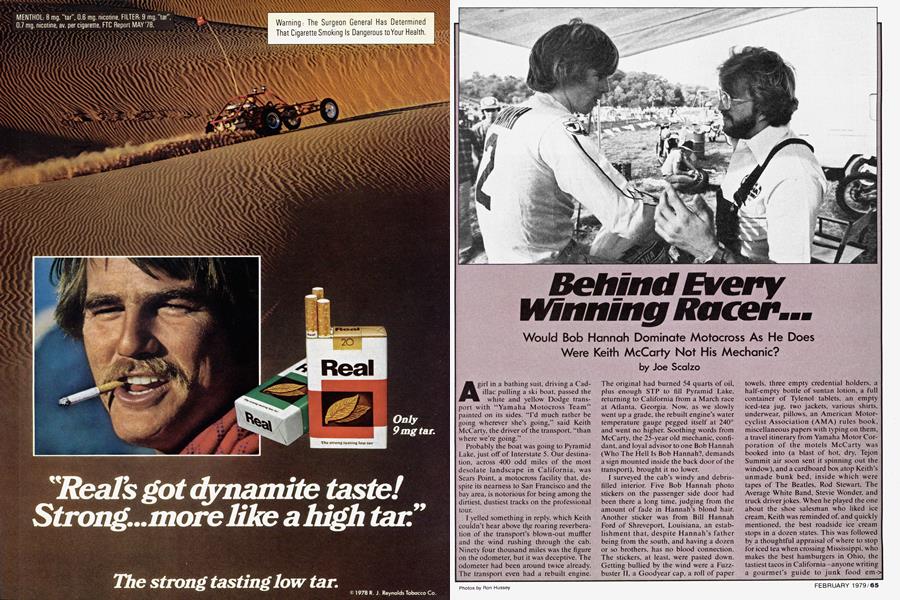

Behind Every Winning Racer...

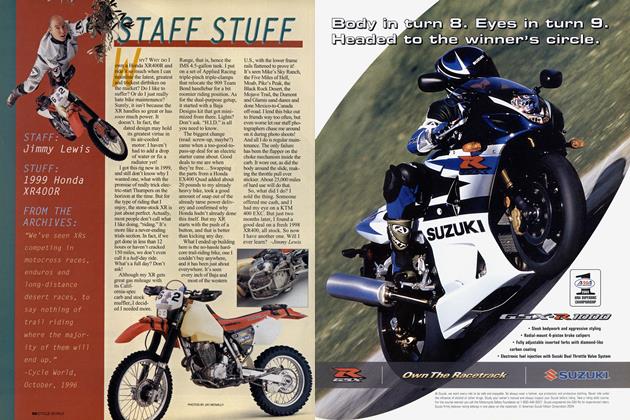

Would Bob Hannah Dominate Motocross As He Does Were Keith McCarty Not His Mechanic?

Joe Scalzo

A girl in a bathing suit, driving a Cadillac pulling a ski boat, passed the white and yellow Dodge transport with “Yamaha Motocross Team” painted on its sides. “I’d much rather be going wherever she’s going,” said Keith McCarty, the driver of the transport, “than where we’re going.”

Probably the boat was going to Pyramid Lake, just off of Interstate 5. Our destination, across 400 odd miles of the most desolate landscape in California, was Sears Point, a motocross facility that, despite its nearness to San Francisco and the bay area, is notorious for being among the dirtiest, dustiest tracks on the professional tour.

I yelled something in reply, which Keith couldn’t hear above the roaring reverberation of the transport’s blown-out muffler and the wind rushing through the cab. Ninety four thousand miles was the figure on the odometer, but it was deceptive. The odometer had been around twice already. The transport even had a rebuilt engine.

The original had burned 54 quarts of oil, plus enough STP to fill Pyramid Lake, returning to California from a March race at Atlanta, Georgia. Now, as we slowly went up a grade, the rebuilt engine’s water temperature gauge pegged itself at 240° and went no higher. Soothing words from McCarty, the 25-year old mechanic, confidant, and loyal advisor to one Bob Hannah (Who The Hell Is Bob Hannah?, demands a sign mounted inside the back door of the transport), brought it no lower.

I surveyed the cab’s windy and debrisfilled interior. Five Bob Hannah photo stickers on the passenger side door had been there a long time, judging from the amount of fade in Hannah’s blond hair. Another sticker was from Bill Hannah Ford of Shreveport, Louisiana, an establishment that, despite Hannah’s father being from the south, and having a dozen or so brothers, has no blood connection. The stickers, at least, were pasted down. Getting bullied by the wind were a Fuzzbuster H, a Goodyear cap, a roll of paper towels, three empty credential holders, a half-empty bottle of suntan lotion, a full container of Tylenol tablets, an empty iced-tea jug, two jackets, various shirts, underwear, pillows, an American Motorcyclist Association (AMA) rules book, miscellaneous papers with typing on them, a travel itinerary from Yamaha Motor Corporation of the motels McCarty was booked into (a blast of hot, dry, Tejón Summit air soon sent it spinning out the window), and a cardboard box atop Keith’s unmade bunk bed, inside which were tapes of The Beatles, Rod Stewart, The Average White Band, Stevie Wonder, and truck driver jokes. When he played the one about the shoe salesman who liked ice cream, Keith was reminded of, and quickly mentioned, the best roadside ice cream stops in a dozen states. This was followed by a thoughtful appraisal of where to stop for iced tea when crossing Mississippi, who makes the best hamburgers in Ohio, the tastiest tacos in California—anyone writing a gourmet’s guide to junk food em-> poriums, it became obvious, would do well to consult this man.

Meanwhile, in the rear of the van, where everything was so fastidiously clean that you could have, without hesitation, eaten off the green carpeted floor, a yellow and black Yamaha 250 motocross racer. No. 2, and 1500 pounds of tackle including spare wheels, tires, engines and tools were stowed away in textbook order. The stark contrast between his spotless working and disheveled living quarters might be comic, except that it is compelling evidence that Keith McCarty has his priorities in order. When Yamaha got him his new transport in a couple of weeks, he said, he would try and find time to be a better housekeeper.

What time? It was June, but he had been on the road since January and would continue to be until November. Traveling, not racing, must take up 80 percent of a racing mechanic’s life. The big indoor motocross meets in Washington. Georgia, Florida, Texas, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Louisiana had come and gone so fast it was hard remembering them anymore, and the outdoor 250cc races, the second of three AMA series (the third is the Trans-AMA,) that Yamaha pays Keith for, already were at hand. On the day I was sitting next to him in the cab, Keith McCarty had, I calculated roughly, been to 13 national races, in half a dozen states, in six months. However many times (Keith himself doesn’t know) he has driven back and forth across the continent to one race or another, during 1974, ’75, ’76, ’77, and now ’78, has worn out a score of van transports, but so far not Keith. And, of course, when he arrives at a race is when his serious work begins.

Inside the steel and glass cab it was baking, and the temperature, as we crossed the almost windless San Joaquin Valley, had climbed to above 100. But even though perspiration was dripping from both ends of McCarty’s obligatory moustache (everyone in the sport, including Hannah, seems to have one), Keith resolutely kept the air conditioning button on Off. Ironically, the air conditioning was one of the few accessories on the worn-out transport that still worked. The reason it worked was because it never, ever, got used. Keith similarly leaves the air conditioning off in motel rooms, garages, and anywhere else he finds himself indoors while on the road. Despite serious health problems when he was younger, he has the constitution of an athlete. He’d better. Being the mechanic, not to mention the close personal friend, of the physically hyperactive Hannah, whose off-track moments are spent water skiing, surfing, hunting, skeet shooting, swimming, running and generally burning up enormous amounts of energy, requires stamina. However, the idea of staying in good physical condition by foregoing air conditioning and adapting to every new temperature, climate and altitude he encounters is not. Keith admits, an original one: the smarter mechanics were doing it long before he got into motocross. The riders always did it.

And although the riders, properly, still get the majority of the glory and acclaim, more and more in motocross the realization seems to be taking hold that a mechanic can make or break a rider. Would Bob Hannah dominate motocross as he does were Keith not his mechanic? Is the reason Tony DiStefano doesn’t dominate as he used to because Keith is no longer his mechanic? No one can say, and Keith himself certainly won’t. All that is clear is that any mechanic, unless he works with an outstanding rider, one who wins frequently, is guaranteed a career of relative anonymity. Had it not been for DiStefano and Hannah, nobody might have heard of Keith McCarty. Yet Keith’s story, in its way, is just as interesting and unlikely as Hannah’s own.

Born without the sense of hearing in his left ear, and with no neck muscles on his left side, and without the ability to breath through his left nostril (he still has an accompanying high nasal intonation). Keith, raised in Southern California, also had a congenitally weak heart that later limited his physical education classes in high school. He went through six operations before he was 10, including open heart surgery at seven. Without overstating the obvious, he overcame much to get where he is today.

He never went to school to become a racing mechanic; no such school exists. “No,” Keith says, “I was lucky.” By lucky, he means that when he still was relatively young he was fortunate enough to discover an occupation which rewarded his mechanical aptitude (more about this in a moment) while also satisfying his appetite for competition. Although he doesn’t have, and apparently never had, a desire to race motorcycles himself, Keith McCarty seems to be a competitor. He hates to lose at anything. He is further lucky, he feels, to be working for a company, Yamaha, which also hates to lose (winning every 1978 motocross championship, a first), and which reportedly pays its racing mechanics as much or more, and gives them greater security, than most teams.

The way Keith got into motocross was circuitous. His physical inability to go out for sports in high school led him to semester after semester of machine shop courses. Whether he had an intuitive feel for them, or developed one, he excelled in such classes. In his senior year came a mechanical award, and an accompanying job offer from the Ford Motor Company, which he never followed through on. Had he done so, motocross might never have heard of him. Instead, when he got out of school, Keith worked for a brief time in an engine rebuilding plant and, for an even briefer period for the short-lived motorcycle division of one of the most flamboyant and obnoxious of Southern California automobile dealerships. He owned and rode motorcycles (he and a brother actually constructed a Harley chopper, a particularly garish one, for exhibit at custom shows) and then, though a friend, heard about a mechanic’s opening on Suzuki’s motocross team.

Turned down for that position, he instead was offered a job in Suzuki’s service and parts section at the main headquarters in Santa Fe Springs, near Los Angeles. A year and a half later, in 1974, the racing job came open again and McCarty worked, in turn, with Mike Runyard, Billy Grossi and, ultimately and most successfully, DiStefano, who won two seasonal 250 titles. In those hectic days McCarty rarely noticed the slim, quiet, teenager who hung around Suzuki and occasionally raced in the 125 class. Later Bob Hannah told Keith that he always wanted to talk to him, but McCarty seemed too busy.

In 1977, when McCarty left Suzuki to go to Yamaha, and Hannah’s old mechanic ■.............................. ..................................»..................— Bill Buchka, who helped Hannah win the 125ce national title as a rookie, left Yamaha and joined Honda in Europe, McCarty and Hannah became a team. Now. one year and one Supercross series championship later (Hannah, in a matter of weeks, would add another Supercross title, and also the 1978 250 championship), they remained a team, in fact the passenger seat in the overheated cab absorbing my perspiration as Keith and I proceeded to Sears Point, normally would have been occupied by Hannah. This weekend he was coming by air.

“When Em driving and Bob sits there talking,” McCarty said, “sometimes he’ll randomly say something about the way the bike felt that day that will really ring a bell with me. It gives an insight into the sort of power curve, gearing, and so forth, that can help him. Bob’s good that way. And he thinks and talks an awful lot after a race.”

The other part of the story is that by traveling on the road with McCarty, instead of first class in a plane, expenses paid by Yamaha, Hannah purposely shares with his mechanic some of the hardship, tedium and boredom that is so much a part of the racing. It is a thoughtful gesture, but he has other ways of rewarding Keith. The expensive watch Keith wears was a gift Hannah brought him following one of his trips to Japan for Yamaha. Correspondingly, the pair of matched rings, made from five dollar gold pieces, that both rider and mechanic wear, were gifts from McCarty’s mother, celebrating the 1977 Supercross title. Astonishingly, in two seasons together McCarty and Hannah have yet to experience a really serious quarrel, and two seasons happens to be a lifetime in something as eruptive as professional motocross. Pictures on the wall of McCarty’s garage in Southern California show' him smiling w ith DiStefano, still a close friend, but once a far closer one. Their highlysuccessful rider-mechanic relationship, which brought in those back-to-back 250 titles, broke up. essentially, over what started as a minor disagreement about the type of front fender DiStefano wanted.

“A rider can become a different person when he starts winning, compared to getting seconds, third, and fourths,” McCarty says. “But when Bob and I got together in 1977. he’d already won his first national title, and I was coming from Tony, so between us we were accustomed to winning. That helped.

“What also helps.” he went on, “is that even though we’re friends. Bob and I are professionals. He knows I wouldn't work as hard as I do if he didn’t work as hard, and put the effort into riding, that he does. We both respect each other, which is the important thing—more important even than money. Yamaha pays me a straight salary, and Bob gets a salary and also keeps all the prize money. I wouldn’t want it any other way, because he earns it. If he was paying me a percentage of his winnings, and he didn’t win, it would be too easy for me to blame him and gripe ‘Look at that. Bob just cost me $150.' Ed rather that when he rewards me, it comes from Bob’s heart.”

McCarty, who has an Irish-English father. and an Armenian mother (he is a distant nephew of the racing entrepreneur J.C. Agajanian), and Hannah, who apparently is of Scotch, Irish, and French-Canadian stock are (McCarty is speaking) “Pretty emotional people, really. People who don’t know' Bob think he has an easier time showing his negative feelings than he does his positive ones, but he’s really a warm person who cares a lot about and does things for his family and friends. Me,

I have an easier time showing my positive feelings than I do my negative ones. I feel lucky to be doing what I am. So many people, as they get older, can’t be perfectionists anymore. They have to settle for second-best. Bob and I are both young enough, and I think dedicated enough, where we haven't gotten to that point. I don't think either of us ever will, if we can help it.”

“Of course,” he said, “it’s easy for me not to be moody now. Bob’s leading the point standings. Everything’s going so well for us. Maybe I wouldn’t be smiling if things weren’t going the way they are.”

Perhaps not. Keith is quite intense about his motocross, about winning, and is encyclopedic about everything from the texture of sand found on the race tracks of Florida (finely textured, it insidiously works its way inside chain links), to the coarser dirt found elsewhere, and what horrors it dishes out to tires and engines, about sand vs. dirt tracks generally, about engine-building and theory, and about suspensions, wheels, spokes, tires, spring rates and countless other things, including who truly goes fast and who does not. Plainly, it would distress Keith to have Hannah run in the back instead of the front. He might w^ell lose his even-tempered manner that is as rare in a mechanic as it is in anyone else who has anything to do w'ith racing.

But a slogan he intends putting on the dashboard of his new transport says something about Keith McCarty, too.

“The vibes you send out (it reads) return home in due time.”

If you cannot get to know' something about a person after spending 10 hours with them inside a heart-strickened transport truck, you never will. I think Keith really believes, and does his best to observe, the law of karma. Additionally, he has an interest in, and a comprehensive knowledge of, a great number of subjects besides motocross and junk food. Without working hard at it, he’s an accomplished raconteur. And an often surprisingly funny person.

On the other hand, the light punching bag mounted inside the back door of the transport is for the use of Yamaha's star mechanic rather than its star rider, Hannah. To release his pent-up disappointment and frustration when things go badly, as they sometimes do, McCarty reluctantly admits he needs something to bash. At Mt. Morris, Pennsylvania, a year ago, things got about as bad as they can get. An apparent double victory for Hannah turned instead, thanks to a pair of thrown chains, into a double Did Not Finish. McCarty’s afternoon was made abominable in triplicate because of a runin with a surly AMA official. After the races, motorists on the main highway out of Mt. Morris couldn’t help noticing the transport parked off to the side, back door flung open, and some madman in the road mindlessly abusing a punching bag. It was Keith.

“I only got about halfway back to the motel,” he said, apologetically, “when all the disappointment and stuff hit me so hard that I just had to stop and punch something.” He said, “It made me feel better.”

At Sears Point Keith didn’t have to sock the bag again, but in a crowded motel room at the Holiday Inn, he somehow managed to get into a good-humored, if strength-sapping, no-holds-barred wrestling match with one of his best racing friends, a big-bellied mechanic named Bevo Forti. A jovial, thick-necked Pennsylvanian with a smile that lights up like Christmas at the sight of food, big Bevo, when he isn’t doing a laudable job of tuning the machines of independent rider John Savitski, is renowned for his appetite, and the money his prowess as a spectacular eater has won him. “Alligator Jaws,” as McCarty named him, once won a bet by taking tw'o full-sized slices of pizza, folding them double, and swallowing them. A contest between himself. McCarty, Hannah and Savitski about which of the quartet could eat a doughnut the fastest was won by Bevo despite the allegation that he cheated by, again, not chewing. McCarty. Hannah, Savitski and Bevo seem to have fun with their bets. Another time Bevo lost face, plus $125 of his and McCarty’s money, to Hannah and Savitski for not quite being able to put away an entire eight-inch peach pie in six minutes. His alibi was that he’d just consumed three hamburgers and dessert.

In any case, at Sears Point, McCarty caught the other mechanic in the act of going through the chest of food McCarty had purchased for Hannah and himself to eat during the morrow’s race (Hawaiian punch, orange juice, peanut butter, roast beef, Roman Meal bread, etc.). A wrestling match broke out. It raged back and forth over the floor and across the tops of beds for a good five minutes before Bevo finally got Keith, still fighting and thrashing, spread-eagled. Then he slowly began strangling him with his stomach until Keith had to wave quit.

Nothing so dramatic happened at the motocross (wrestling bouts between Keith and Bevo happen frequently, apparently always with the same result), but it was instructive watching how someone like Keith works.

continued on page 112

continued from page 68

Hannah, whose plane from Los Angeles arrived late, immediately came down with hay fever, a malady he suffers from worse than most people. He still had the strength of will to repel a hard charge from Jim Ellis and win the first of two 45-minute motos. During the intermission, under the shade of an awning Keith had put up next to the transport van, and wdping down his face with a towel he had brought w ith him from the motel, Hannah sat in a camp chair, fogging the dusty air with raking sneezes. Keith worked. He had something like half an hour to rebuild a motorcycle that Hannah had had to overwork to hold off Ellis. No. 2 seemed, to me, to be thoroughly trashed. Keith was too busy to talk although Hannah, between sneezes, tried to.

Hannah: “Keith, I had a hole shot at the start, but I blew' the first turn. Didn’t know how to handle it. I should have practiced more.”

Keith: “Saw that.”

Hannah: “Em not riding right.”

Keith: “Everyone else must be riding worse.”

Hannah: “I was riding hardest the last four laps because Ellis was catching me. You should have heard him. He was yelling at me while we were racing. I heard him yelling ‘Hey, Bob!’ ”

Keith: “What?”

Hannah: “I hope Ellis isn’t going to want to race as hard this next moto as he did the last one.”

Keith: “Oh.”

So much for dramatic conversation and shrewd tactics between rider and mechanic. It would be superfluous, anyway because Hannah isn’t the kind of competitor who requires a pep talk, and Keith knew exactly what he had to do to No. 2. In the limited amount of time he had he attacked the tires, frame, footpegs and chain (careful not to hit the master link) with a wire brush until an almost 6-inch mound of dirt and mud from the track appeared under No. 2; checked the frame, wheels, and spokes for fractures; changed the air filter; tightened the spokes, handlebars, and everything else; debated changing to fresh tires and decided not to; topped off the fuel and oil; and did other maintenance that I can’t remember.

Sears Point was hot, dry and dusty, and Keith must have been parched, but not until he was through did I see him take his first drink of anything. He never got to sit down, not once, and he had already been on his feet signaling Hannah throughout the first moto.

Hannah, helmet in place, rode off to the starting line and Keith followed carrying a signaling blackboard and tools. Hannah's sneezing worsened on the starting line and Keith had to run all the way back to the pits again for Kleenex. Holding a stop watch in front of Hannah with his right hand, massaging Hannah’s back with his left, Keith stepped back just as the starting gate dropped and dirt clods and engine exhaust exploded backwards through the air.

Sprinting with the blackboard and tools to the signaling area, Keith spent the following 45 minutes signaling and worrying, signaling and worrying. He saw almost nothing of the race. Located in one of the lowest points of the track. Sears Point’s signaling area is no place for spectating. What must it be like to have your machine and rider hurtling around and around yet never be able to see them? Keith missed the pass that Marty Tripes put on Hannah that won Tripes the moto and dropped Hannah to second; and though afterwards he looked at it with curiosity, he never knew where all the green paint came from on No. 2’s front forks. Hannah told me it was off of Jim Weinert’s Kawasaki: that after Weinert had rammed him, he, Hannah, gave it back to him, fracturing two spokes off his own front wheel, but still couldn’t stop Weinert from beating him out of second place.

Nevertheless, even with a display of riding that everyone seemed to agree was, for him, substandard, Hannah, with one victory and one third place, was overall winner of the meet.

“Even on a bad day,” Keith exulted, driving the transport out of the race track, starting to unwind, to talk again and savor another victory, “Bob wins.”

Hannah, still sneezing, was seated on the passenger side.

“How can Marty Tripes go that fast on a 250?” I asked. Tripes, a massive 200-lb. rider, once had a reputation for eating second only to Bevo Forti’s.

“His weight helps him,” said Hannah. “It’s where he gets traction”

“But the Honda team won’t let him eat on race day, I don’t think.” said Keith. “They worry that he’ll get as heavy as he used to be. He couldn’t do anything then.” (A week later, at St. Peters, Missouri, Keith and Bevo slipped past the watchful Honda mechanics and fed and stuffed a hungry Marty Tripes full of the biggest hero sandwich Bevo had been able to make. It was supposed to be a prank. Prank or not, Hannah subsequently won both motos, clinched the 250 season championship, and Tripes, his vanquisher at Sears Point, was nowhere to be seen.)

Suddenly Hannah looked up and realized what was happening. Keith was in the middle of a drag race to the narrow Sears Point exit with the transports of two other Yamaha mechanics, Jim West and bushyhaired Dave Osterman, who Hannah called “Brillo.”

“No. Keith, no!” Hannah implored. “No! Watch it! Slow down! Brillo doesn’t see you! He’s not looking!”

Discovering that Bob Hannah, of all people, was an inveterate backseat driver was startling. But mechanics must win their races, too.

“We beat them on the track,” said Keith., moving ahead of Brillo.

“Now' we beat them off the track.” S3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

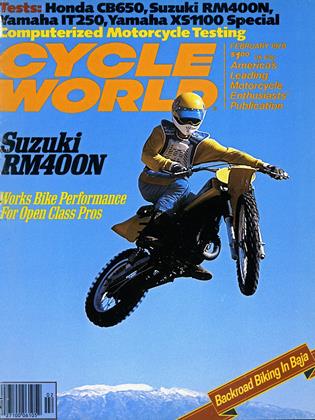

Up Front

Up FrontWhy the Future Isn't My Secret

February 1979 By Allan Girdler -

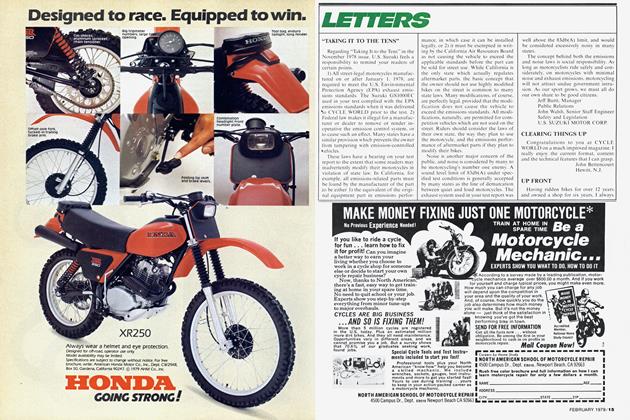

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1979 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound-Up

February 1979 -

Short Strokes

February 1979 By Tim Barela -

Technical

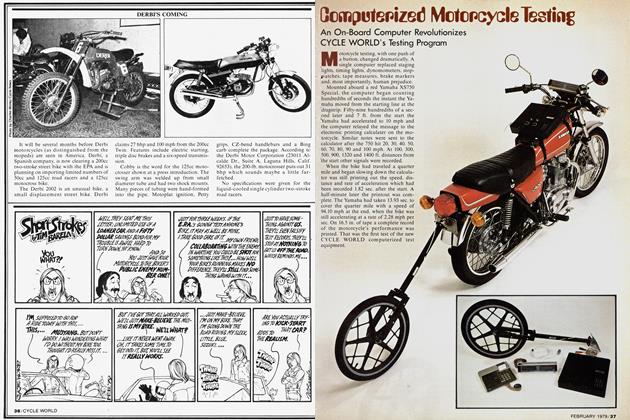

TechnicalComputerized Motorcycle Testing

February 1979 -

Features

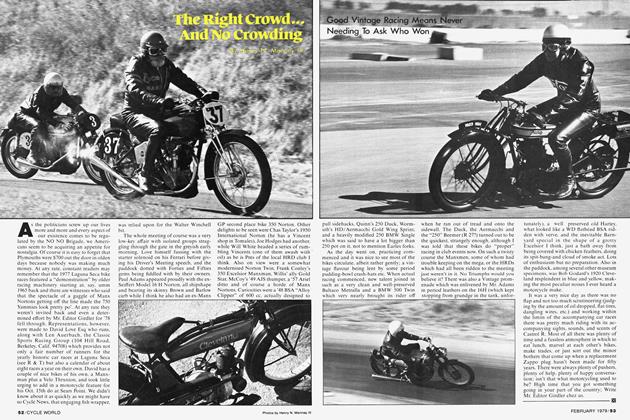

FeaturesThe Right Crowd... And No Crowding

February 1979 By Henry N. Manney III