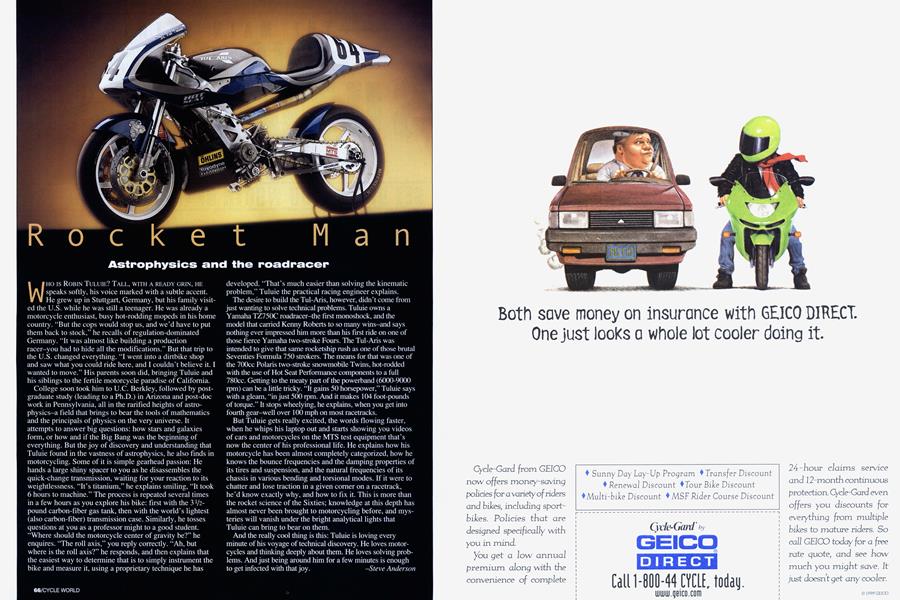

Rocket Man

Astrophysics and the roadracer

WHO IS ROBIN TULUIE? TALL, WITH A READY GRIN, HE speaks softly, his voice marked with a subtle accent. He grew up in Stuttgart, Germany, but his family visited the U.S. while he was still a teenager. He was already a motorcycle enthusiast, busy hot-rodding mopeds in his home country. “But the cops would stop us, and we’d have to put them back to stock,” he recalls of regulation-dominated Germany. “It was almost like building a production racer-you had to hide all the modifications.” But that trip to the U.S. changed everything. “I went into a dirtbike shop and saw what you could ride here, and I couldn’t believe it. I wanted to move.” His parents soon did, bringing Tuluie and his siblings to the fertile motorcycle paradise of California.

College soon took him to U.C. Berkley, followed by postgraduate study (leading to a Ph.D.) in Arizona and post-doc work in Pennsylvania, all in the rarified heights of astrophysics-a field that brings to bear the tools of mathematics and the principals of physics on the very universe. It attempts to answer big questions: how stars and galaxies form, or how and if the Big Bang was the beginning of everything. But the joy of discovery and understanding that Tuluie found in the vastness of astrophysics, he also finds in motorcycling. Some of it is simple gearhead passion: He hands a large shiny spacer to you as he disassembles the quick-change transmission, waiting for your reaction to its weightlessness. “It’s titanium,” he explains smiling, “It took 6 hours to machine.” The process is repeated several times in a few hours as you explore his bike: first with the 3 l/2pound carbon-fiber gas tank, then with the world’s lightest (also carbon-fiber) transmission case. Similarly, he tosses questions at you as a professor might to a good student. “Where should the motorcycle center of gravity be?” he enquires. “The roll axis,” you reply correctly. “Ah, but where is the roll axis?” he responds, and then explains that the easiest way to determine that is to simply instrument the bike and measure it, using a proprietary technique he has developed. “That’s much easier than solving the kinematic problem,” Tuluie the practical racing engineer explains.

The desire to build the Tul-Aris, however, didn’t come from just wanting to solve technical problems. Tuluie owns a Yamaha TZ750C roadracer-the first monoshock, and the model that carried Kenny Roberts to so many wins-and says nothing ever impressed him more than his first ride on one of those fierce Yamaha two-stroke Fours. The Tul-Aris was intended to give that same rocketship rush as one of those brutal Seventies Formula 750 strokers. The means for that was one of the 700cc Polaris two-stroke snowmobile Twins, hot-rodded with the use of Hot Seat Performance components to a full 780cc. Getting to the meaty part of the powerband (6000-9000 rpm) can be a little tricky. “It gains 50 horsepower,” Tuluie says with a gleam, “in just 500 rpm. And it makes 104 foot-pounds of torque.” It stops wheelying, he explains, when you get into fourth gear-well over 100 mph on most racetracks.

But Tuluie gets really excited, the words flowing faster, when he whips his laptop out and starts showing you videos of cars and motorcycles on the MTS test equipment that’s now the center of his professional life. He explains how his motorcycle has been almost completely categorized, how he knows the bounce frequencies and the damping properties of its tires and suspension, and the natural frequencies of its chassis in various bending and torsional modes. If it were to chatter and lose traction in a given comer on a racetrack, he’d know exactly why, and how to fix it. This is more than the rocket science of the Sixties; knowledge at this depth has almost never been brought to motorcycling before, and mysteries will vanish under the bright analytical lights that Tuluie can bring to bear on them.

And the really cool thing is this: Tuluie is loving every minute of his voyage of technical discovery. He loves motorcycles and thinking deeply about them. He loves solving problems. And just being around him for a few minutes is enough to get infected with that joy.

Steve Anderson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Parkhurst Papers

March 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsStocking Up

March 2001 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCEarly Days, Good Days

March 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

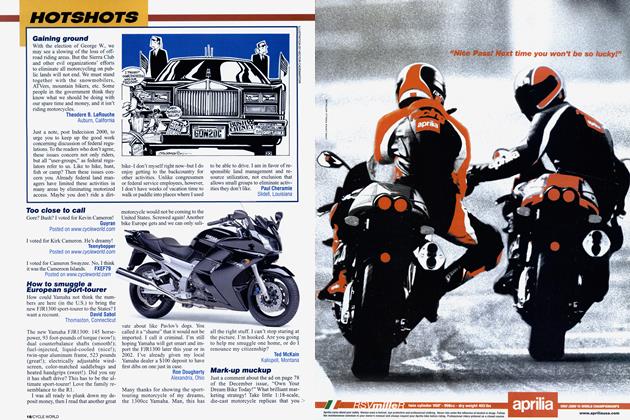

DepartmentsHotshots

March 2001 -

Roundup

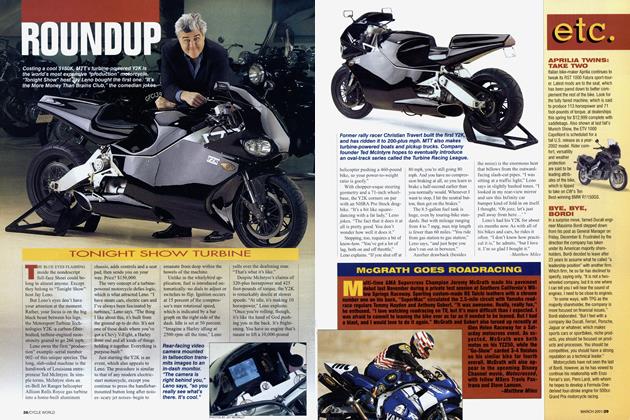

RoundupTonight Show Turbine

March 2001 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

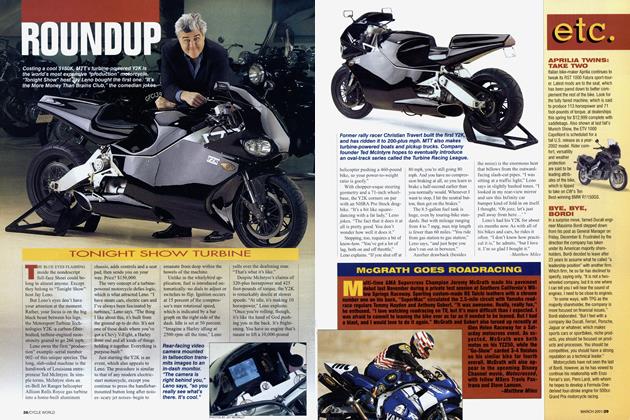

RoundupMcgrath Goes Roadracing

March 2001 By Matthew Miles