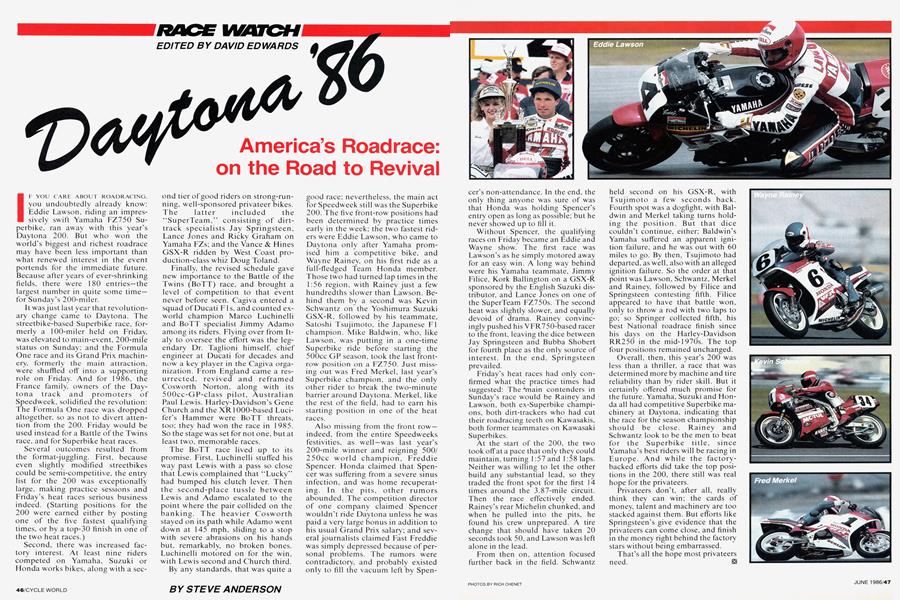

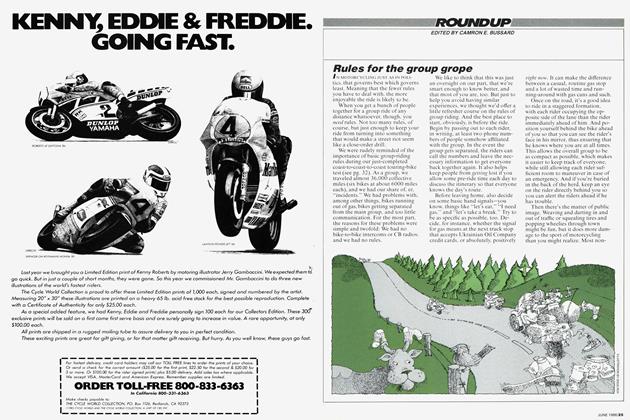

Daytona '86

RACE WATCH

America's Road race: on the Road to Revival

DAVID EDWARDS

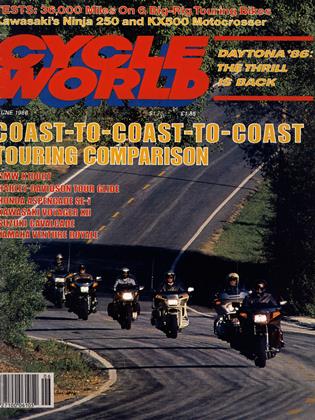

IF YOU CARE ABOUT ROADRACING, you undoubtedly already know: Eddie Lawson, riding an impressively swift Yamaha FZ750 Superbike, ran away with this year’s Daytona 200. But who won the world's biggest and richest roadrace may have been less important than what renewed interest in the event portends for the immediate future. Because after years of ever-shrinking fields, there were 180 entries—the largest number in quite some time— for Sunday’s 200-miler.

It was just last year that revolutionary change came to Daytona. The streetbike-based Superbike race, formerly a 100-miler held on Friday, was elevated to main-event. 200-mile status on Sunday; and the Formula One race and its Grand Prix machinery, formerly the main attraction, were shuffled off into a supporting role on Friday. And for 1986, the France family, owners of the Daytona track and promoters of Speedweek, solidified the revolution: The Formula One race was dropped altogether, so as not to divert attention from the 200. Friday would be used instead for a Battle of the Twins race, and for Superbike heat races.

Several outcomes resulted from the format-juggling. First, because even slightly modified streetbikes could be semi-competitive, the entry list for the 200 was exceptionally large, making practice sessions and Friday’s heat races serious business indeed. (Starting positions for the 200 were earned either by posting one of the five fastest qualifying times, or by a top-30 finish in one of the two heat races.)

Second, there was increased factory interest. At least nine riders competed on Yamaha. Suzuki or Honda works bikes, along with a second tier of good riders on strong-running, well-sponsored privateer bikes. The latter included the “SuperTeam,” consisting of dirttrack specialists Jay Springsteen, Lance Jones and Ricky Graham on Yamaha FZs; and the Vance & Hines GSX-R ridden by West Coast production-class whiz Doug Toland.

Finally, the revised schedule gave new importance to the Battle of the Twins (BoTT) race, and brought a level of competition to that event never before seen. Cagiva entered a squad of Ducati FIs, and counted exworld champion Marco Luchinelli and BoTT specialist Jimmy Adamo among its riders. Flying over from Italy to oversee the effort was the legendary Dr. Taglioni himself, chief engineer at Ducati for decades and now a key player in the Cagiva organization. From England came a resurrected, revived and reframed Cosworth Norton, along with its 500cc-GP-class pilot, Australian Paul Lewis. Harley-Davidson’s Gene Church and the XR 1000-based Lucifer’s Hammer were BoTT threats, too; they had won the race in 1985. So the stage was set for not one, but at least two, memorable races.

The BoTT race lived up to its promise. First, Luchinelli stuffed his way past Lewis with a pass so close that Lewis complained that “Lucky” had bumped his clutch lever. Then the second-place tussle between Lewis and Adamo escalated to the point where the pair collided on the banking. The heavier Cosworth stayed on its path while Adamo went down at 145 mph, sliding to a stop with severe abrasions on his hands but, remarkably, no broken bones. Luchinelli motored on for the win. with Lewis second and Church third.

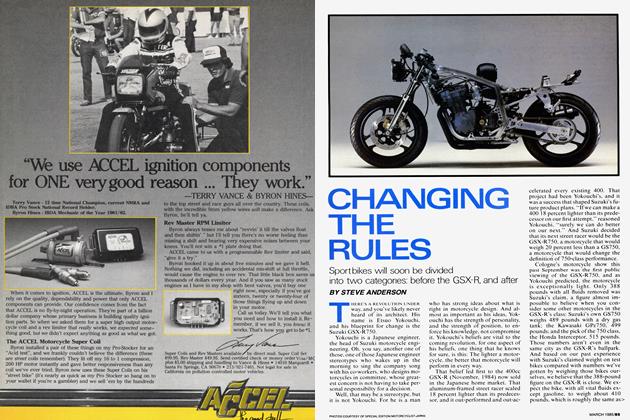

By any standards, that was quite a good race; nevertheless, the main act for Speedweek still was the Superbike 200. The five front-row positions had been determined by practice times early in the week; the two fastest riders were Eddie Lawson, who came to Daytona only after Yamaha promised him a competitive bike, and Wayne Rainey, on his first ride as a full-fledged Team Honda member. Those two had turned lap times in the 1:56 region, with Rainey just a few hundredths slower than Lawson. Behind them by a second was Kevin Schwantz on the Yoshimura Suzuki GSX-R, followed by his teammate, Satoshi Tsujimoto, the Japanese FI champion. Mike Baldwin, who, like Lawson, was putting in a one-time Superbike ride before starting the 500cc GP season, took the last frontrow position on a FZ750. Just missing out was Fred Merkel, last year’s Superbike champion, and the only other rider to break the two-minute barrier around Daytona. Merkel, like the rest of the field, had to earn his starting position in one of the heat races.

Also missing from the front row— indeed, from the entire Speedweeks festivities, as well—was last year’s 200-mile winner and reigning 500/ 250cc world champion, Freddie Spencer. Honda claimed that Spencer was suffering from a severe sinus infection, and was home recuperating. In the pits, other rumors abounded. The competition director of one company claimed Spencer wouldn’t ride Daytona unless he was paid a very large bonus in addition to his usual Grand Prix salary; and several journalists claimed Fast Freddie was simply depressed because of personal problems. The rumors were contradictory, and probably existed only to fill the vacuum left by Spencer’s non-attendance. In the end, the only thing anyone was sure of was that Honda was holding Spencer’s entry open as long as possible; but he never showed up to fill it.

STEVE ANDERSON

Without Spencer, the qualifying races on Friday became an Eddie and Wayne show. The first race was Lawson’s as he simply motored away for an easy win. A long way behind were his Yamaha teammate, Jimmy Filice, Kork Ballington on a GSX-R sponsored by the English Suzuki distributor, and Lance Jones on one of the SuperTeam FZ750s. The second heat was slightly slower, and equally devoid of drama. Rainey convincingly pushed his VFR750-based racer to the front, leaving the dice between Jay Springsteen and Bubba Shobert for fourth place as the only source of interest. In the end, Springsteen prevailed.

Friday’s heat races had only confirmed what the practice times had suggested: The 'main contenders in Sunday’s race would be Rainey and Lawson, both ex-Superbike champions, both dirt-trackers who had cut their roadracing teeth on Kawasakis, both former teammates on Kawasaki Superbikes.

At the start of the 200, the two took off at a pace that only they could maintain, turning 1:57 and 1:58 laps. Neither was willing to let the other build any substantial lead, so they traded the front spot for the first 14 times around the 3.87-mile circuit. Then the race effectively ended. Rainey’s rear Michelin chunked, and when he pulled into the pits, he found his crew unprepared. A tire change that should have taken 20 seconds took 50, and Lawson was left alone in the lead.

From then on, attention focused further back in the field. Schwantz held second on his GSX-R, with Tsujimoto a few seconds back. Fourth spot was a dogfight, with Baldwin and Merkel taking turns holding the position. But that dice couldn't continue, either; Baldwin’s Yamaha suffered an apparent ignition failure, and he was out with 60 miles to go. By then, Tsujimoto had departed, as well, also with an alleged ignition failure. So the order at that point was Lawson, Schwantz, Merkel and Rainey, followed by Filice and Springsteen contesting fifth. Filice appeared to have that battle won, only to throw a rod with two laps to go; so Springer collected fifth, his best National roadrace finish since his days on the Harley-Davidson RR250 in the mid-1970s. The top four positions remained unchanged.

Overall, then, this year’s 200 was less than a thriller, a race that was determined more by machine and tire reliability than by rider skill. But it certainly offered much promise for the future. Yamaha, Suzuki and Honda all had competitive Superbike machinery at Daytona, indicating that the race for the season championship should be close. Rainey and Schwantz look to be the men to beat for the Superbike title, since Yamaha’s best riders will be racing in Europe. And while the factorybacked efforts did take the top positions in the 200, there still was real hope for the privateers.

Privateers don’t, after all, really think they can win; the cards of money, talent and machinery are too stacked against them. But efforts like Springsteen’s give evidence that the privateers can come close, and finish in the money right behind the factory stars without being embarrassed.

That’s all the hope most privateers need. S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue