EDITORIAL

Watching paint dry

LYDIA HENSHAW IS A SPORTSWRITER. working for a small newspaper. Like most sportswriters, she spends her time covering ball sports: basketball, and football, and baseball, the meat of the sports pages. She writes about the local teams, and, in her column, entertains with major-league news as well. Nothing out of the ordinary.

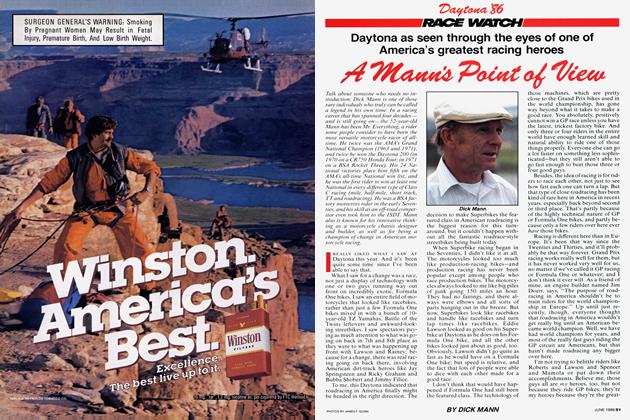

What separates Ms. Henshaw from most of her colleagues is her newspaper: the Daytona Beach News Journal. For a sportswriter, having the Daytona Speedway in your hometown adds spice to that meaty diet; there are stock-car races, sportscar endurance races, and, of course, the Daytona 200 motorcycle race.

Fve never met Lydia Henshaw, but I do have something in common with her: I, too, was at the Daytona Speedway this year, reporting on the 200. And while the race wasn’t anywhere near a classic, with Eddie Lawson winning unchallenged after Wayne Rainey’s tire problems, it was exciting. When I left afterwards, I was well-satisified.

Accordingly, Monday morning’s sports section in the News Journal was quite a shock. “I came, I saw, I was bored,” was the headline of Ms. Henshaw’s column, which went on to savage the entertainment value of the 200-mile race.

My first reaction was a reflexive defensiveness: I had enjoyed the race, so why hadn’t Ms. Henshaw? Didn’t she like motorcycles? As I read through her column, I felt increasingly disconnected. Had we even seen the same race, I wondered?

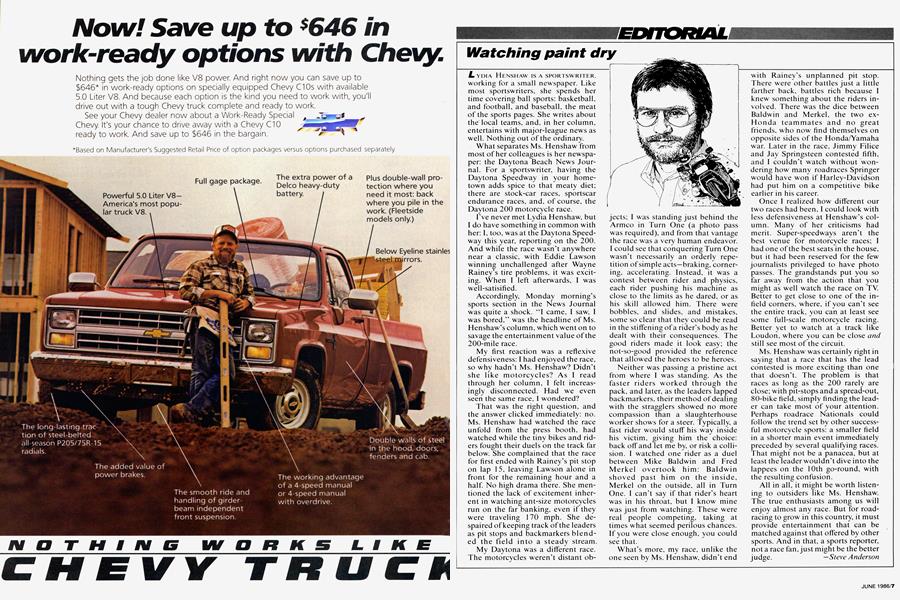

That was the right question, and the answer clicked immediately: no. Ms. Henshaw had watched the race unfold from the press booth, had watched while the tiny bikes and riders fought their duels on the track far below. She complained that the race for first ended with Rainey’s pit stop on lap 15, leaving Lawson alone in front for the remaining hour and a half. No high drama there. She mentioned the lack of excitement inherent in watching ant-size motorcycles run on the far banking, even if they were traveling 170 mph. She despaired of keeping track of the leaders as pit stops and backmarkers blended the Field into a steady stream.

My Daytona was a different race. The motorcycles weren’t distant objects; I was standing just behind the Armco in Turn One (a photo pass was required), and from that vantage the race was a very human endeavor. I could see that conquering Turn One wasn’t necessarily an orderly repetition of simple acts—braking, cornering, accelerating. Instead, it was a contest between rider and physics, each rider pushing his machine as close to the limits as he dared, or as his skill allowed him. There were bobbies, and slides, and mistakes, some so clear that they could be read in the stiffening of a rider’s body as he dealt with their consequences. The good riders made it look easy; the not-so-good provided the reference that allowed the heroes to be heroes.

Neither was passing a pristine act from where I was standing. As the faster riders worked through the pack, and later, as the leaders lapped backmarkers, their method of dealing with the stragglers showed no more compassion than a slaughterhouse worker shows for a steer. Typically, a fast rider would stuff his way inside his victim, giving him the choice: back off and let me by, or risk a collision. I watched one rider as a duel between Mike Baldwin and Fred Merkel overtook him: Baldwin

shoved past him on the inside, Merkel on the outside, all in Turn One. I can’t say if that rider’s heart was in his throat, but I know mine was just from watching. These were real people competing, taking at times what seemed perilous chances. If you were close enough, you could see that.

What’s more, my race, unlike the one seen by Ms. Henshaw, didn’t end with Rainey’s unplanned pit stop. There were other battles just a little farther back, battles rich because I knew something about the riders involved. There was the dice between Baldwin and Merkel, the two exHonda teammates and no great friends, who now find themselves on opposite sides of the Honda/Yamaha war. Later in the race, Jimmy Filice and Jay Springsteen contested fifth, and I couldn't watch without wondering how many roadraces Springer would have won if Harley-Davidson had put him on a competitive bike earlier in his career.

Once I realized how different our two races had been, I could look with less defensiveness at Henshaw’s column. Many of her criticisms had merit. Super-speedways aren’t the best venue for motorcycle races; I had one of the best seats in the house, but it had been reserved for the few journalists privileged to have photo passes. The grandstands put you so far away from the action that you might as well watch the race on TV. Better to get close to one of the infield corners, where, if you can’t see the entire track, you can at least see some full-scale motorcycle racing. Better yet to watch at a track like Loudon, where you can be close and still see most of the circuit.

Ms. Henshaw was certainly right in saying that a race that has the lead contested is more exciting than one that doesn’t. The problem is that races as long as the 200 rarely are close; with pit-stops and a spread-out, 80-bike field, simply finding the leader can take most of your attention. Perhaps roadrace Nationals could follow the trend set by other successful motorcycle sports: a smaller field in a shorter main event immediately preceded by several qualifying races. That might not be a panacea, but at least the leader wouldn’t dive into the lappees on the 10th go-round, with the resulting confusion.

All in all, it might be worth listening to outsiders like Ms. Henshaw. The true enthusiasts among us will enjoy almost any race. But for roadracing to grow in this country, it must provide entertainment that can be matched against that offered by other sports. And in that, a sports reporter, not a race fan, just might be the better judge.

Steve Anderson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue