Paying the price

TDC

Kevin Cameron

IN ALL VEHICLES, STABILITY AND REsponsiveness are opposed qualities. When we need hands-off stability—as in designing a large touring bike—the result is a system that rejects all disturbances. This includes our own attempts to steer, so control becomes to a degree heavy and slow. This is the price of stability.

When we want responsiveness above all-as in designing a racing machine-we create a system that is responsive to all inputs, including wind, bumps in the road and wheel imbalance. The result is a machine that responds very quickly to our commands, but which is also twitchy, requiring constant attention. This is the price of responsiveness.

There is an analogy to be made here with the process of human decisionmaking. Stability and responsiveness are again opposed. Stability is useful because our opinions of people are not easily changed by the ups and downs of friendship or marriage, and we are not always flying off in some new direction, instant slaves of the latest guru or other fashion. We are able to reject meaningless disturbances and keep our lives on course.

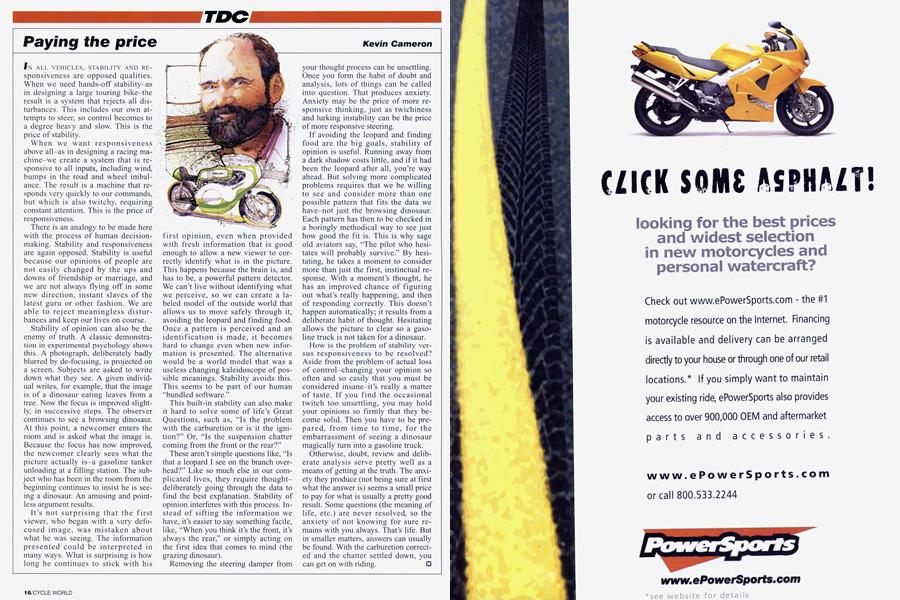

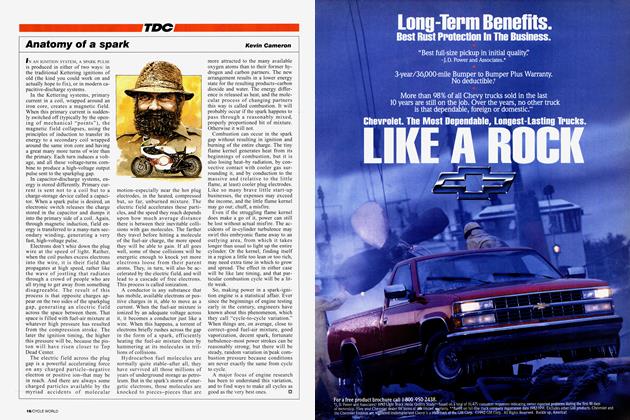

Stability of opinion can also be the enemy of truth. A classic demonstration in experimental psychology shows this. A photograph, deliberately badly blurred by de-focusing, is projected on a screen. Subjects are asked to write down what they see. A given individual writes, for example, that the image is of a dinosaur eating leaves from a tree. Now the focus is improved slightly, in successive steps. The observer continues to see a browsing dinosaur. At this point, a newcomer enters the room and is asked what the image is. Because the focus has now improved, the newcomer clearly sees what the picture actually is-a gasoline tanker unloading at a filling station. The subject who has been in the room from the beginning continues to insist he is seeing a dinosaur. An amusing and pointless argument results.

It’s not surprising that the first viewer, who began with a very defocused image, was mistaken about what he was seeing. The information presented could be interpreted in many ways. What is surprising is how long he continues to stick with his first opinion, even when provided with fresh information that is good enough to allow a new viewer to correctly identify what is in the picture. This happens because the brain is, and has to be, a powerful pattern detector. We can’t live without identifying what we perceive, so we can create a labeled model of the outside world that allows us to move safely through it, avoiding the leopard and finding food. Once a pattern is perceived and an identification is made, it becomes hard to change even when new information is presented. The alternative would be a world model that was a useless changing kaleidoscope of possible meanings. Stability avoids this. This seems to be part of our human “bundled software.”

This built-in stability can also make it hard to solve some of life’s Great Questions, such as, “Is the problem with the carburetion or is it the ignition?” Or, “Is the suspension chatter coming from the front or the rear?”

These aren’t simple questions like, “Is that a leopard I see on the branch overhead?” Like so much else in our complicated lives, they require thoughtdeliberately going through the data to find the best explanation. Stability of opinion interferes with this process. Instead of sifting the information we have, it’s easier to say something facile, like, “When you think it’s the front, it’s always the rear,” or simply acting on the first idea that comes to mind (the grazing dinosaur).

Removing the steering damper from your thought process can be unsettling. Once you form the habit of doubt and analysis, lots of things can be called into question. That produces anxiety. Anxiety may be the price of more responsive thinking, just as twichiness and lurking instability can be the price of more responsive steering.

If avoiding the leopard and finding food are the big goals, stability of opinion is useful. Running away from a dark shadow costs little, and if it had been the leopard after all, you’re way ahead. But solving more complicated problems requires that we be willing to see and consider more than one possible pattern that fits the data we have-not just the browsing dinosaur. Each pattern has then to be checked in a boringly methodical way to see just how good the fit is. This is why sage old aviators say, “The pilot who hesitates will probably survive.” By hesitating, he takes a moment to consider more than just the first, instinctual response. With a moment’s thought, he has an improved chance of figuring out what’s really happening, and then of responding correctly. This doesn’t happen automatically; it results from a deliberate habit of thought. Hesitating allows the picture to clear so a gasoline truck is not taken for a dinosaur.

How is the problem of stability versus responsiveness to be resolved? Aside from the problem of actual loss of control-changing your opinion so often and so easily that you must be considered insane-it’s really a matter of taste. If you find the occasional twitch too unsettling, you may hold your opinions so firmly that they become solid. Then you have to be prepared, from time to time, for the embarrassment of seeing a dinosaur magically turn into a gasoline truck.

Otherwise, doubt, review and deliberate analysis serve pretty well as a means of getting at the truth. The anxiety they produce (not being sure at first what the answer is) seems a small price to pay for what is usually a pretty good result. Some questions (the meaning of life, etc.) are never resolved, so the anxiety of not knowing for sure remains with you always. That’s life. But in smaller matters, answers can usually be found. With the carburetion corrected and the chatter settled down, you can get on with riding.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue