Philosophic conversions

TDC

Kevin Cameron

As A HIGH SCHOOL STUDENT, YEARNING for something beyond pep rallies and spelling disguised as English Literature, I hit upon grand prix auto racing. I dug out precious info on supercharging and I listened to recorded sounds of Mercedes-Benz’s prewar Eights and Twelves. The local library wasn’t much help; all they had was Life and Look and Reader’s Digest.

Off to college, I found better libraries. And book stores. Soon I had a little shelf of titles about Healey, MG and Jaguar. I walked down the avenue and bought the 1953 edition (some unfeeling scoundrel has now stolen this from me) of Harry Ricardo’s High Speed Internal Combustion Engines, and I developed a problem from which I have never been able to recover. Ricardo was the yellow brick road to engine design, performance and understanding; his prose made it clear that more than tradition and craftsmanship lay behind successful engines. Any enthusiasm I might have had for the long-stroke dinosaurs that powered British sports cars deflated over the time I spent reading Ricardo.

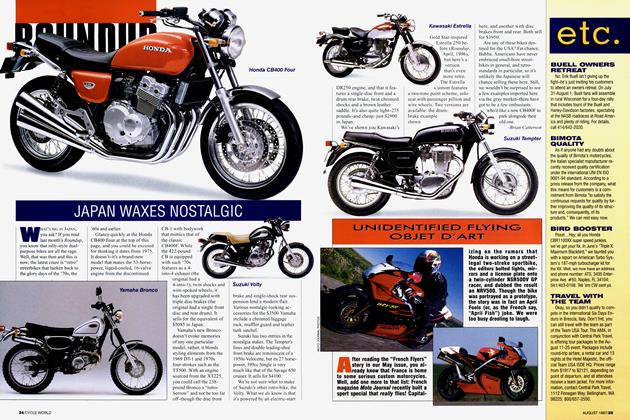

Cars were big and heavy, dripping gritty blobs into the eyes of those who lay beneath them. Motorcycles fitted neatly into college rooms, and their engines were closer by far to Ricardo’s world. I switched my allegiance. From magazines, I learned about England’s highly developed single-cylinder racers-the Manx, the G50, the 7R-and the engineers and tuners behind them. And then I could hear another note, much higher and sharper. I saw a single black-and-white photo in a car magazine, announcing condescendingly that a quaint little company in Japan-Honda-had created a fourcylinder 250cc motorcycle known as the RC160, capable of 13,500 rpm. I wanted to know more about this.

This was the rpm revolution, and I became its passionate partisan. It made sense because it reached rationally for power where power could still be made, at higher revs. It was exciting because it leaped beyond the flogging of tired tradition. Every new British magazine revealed fresh Japanese success. I learned to pronounce the names.

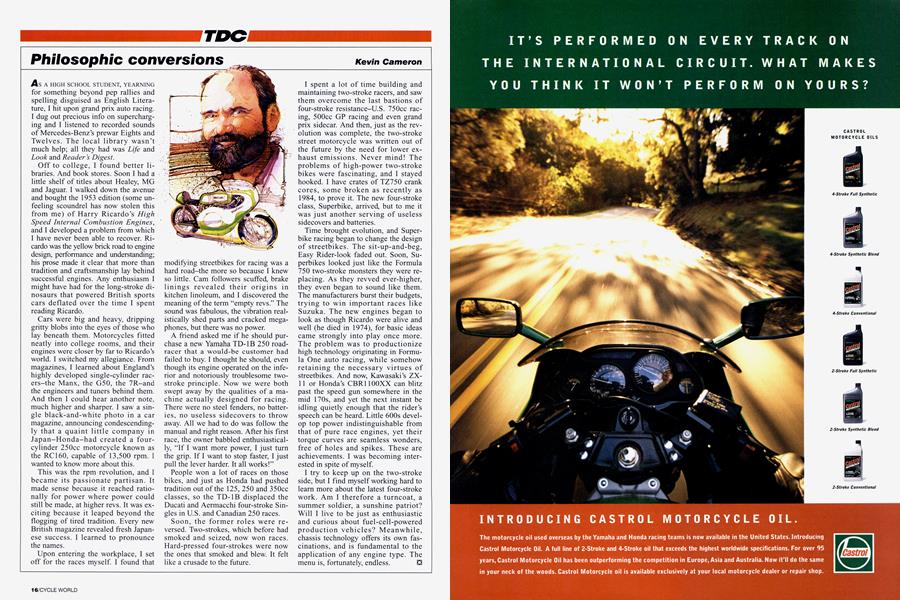

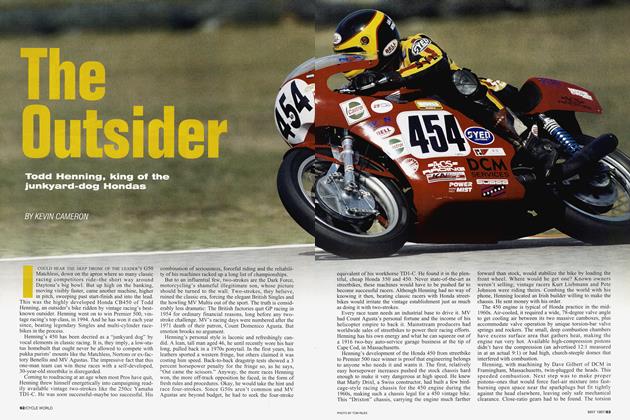

Upon entering the workplace, I set off for the races myself. I found that modifying streetbikes for racing was a hard road-the more so because I knew so little. Cam followers scuffed, brake linings revealed their origins in kitchen linoleum, and I discovered the meaning of the term “empty revs.” The sound was fabulous, the vibration realistically shed parts and cracked megaphones, but there was no power.

A friend asked me if he should purchase a new Yamaha TD-1B 250 roadracer that a would-be customer had failed to buy. I thought he should, even though its engine operated on the inferior and notoriously troublesome twostroke principle. Now we were both swept away by the qualities of a machine actually designed for racing. There were no steel fenders, no batteries, no useless sidecovers to throw away. All we had to do was follow the manual and right reason. After his first race, the owner babbled enthusiastically, “If I want more power, I just turn the grip. If I want to stop faster, I just pull the lever harder. It all works!”

People won a lot of races on those bikes, and just as Honda had pushed tradition out of the 125, 250 and 350cc classes, so the TD-1B displaced the Ducati and Aermacchi four-stroke Singles in U.S. and Canadian 250 races.

Soon, the former roles were reversed. Two-strokes, which before had smoked and seized, now won races. Hard-pressed four-strokes were now the ones that smoked and blew. It felt like a crusade to the future.

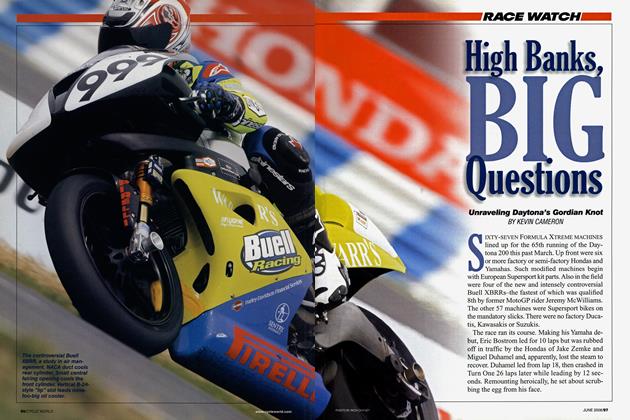

I spent a lot of time building and maintaining two-stroke racers, and saw them overcome the last bastions of four-stroke resistance-U.S. 750cc racing, 500cc GP racing and even grand prix sidecar. And then, just as the revolution was complete, the two-stroke street motorcycle was written out of the future by the need for lower exhaust emissions. Never mind! The problems of high-power two-stroke bikes were fascinating, and I stayed hooked. I have crates of TZ750 crank cores, some broken as recently as 1984, to prove it. The new four-stroke class, Superbike, arrived, but to me it was just another serving of useless sidecovers and batteries.

Time brought evolution, and Superbike racing began to change the design of streetbikes. The sit-up-and-beg, Easy Rider-look faded out. Soon, Superbikes looked just like the Formula 750 two-stroke monsters they were replacing. As they revved ever-higher, they even began to sound like them. The manufacturers burst their budgets, trying to win important races like Suzuka. The new engines began to look as though Ricardo were alive and well (he died in 1974), for basic ideas came strongly into play once more. The problem was to productionize high technology originating in Formula One auto racing, while somehow retaining the necessary virtues of streetbikes. And now, Kawasaki’s ZX11 or Honda’s CBR1100XX can blitz past the speed gun somewhere in the mid 170s, and yet the next instant be idling quietly enough that the rider’s speech can be heard. Little 600s develop top power indistinguishable from that of pure race engines, yet their torque curves are seamless wonders, free of holes and spikes. These are achievements. I was becoming interested in spite of myself.

I try to keep up on the two-stroke side, but I find myself working hard to learn more about the latest four-stroke work. Am I therefore a turncoat, a summer soldier, a sunshine patriot? Will I live to be just as enthusiastic and curious about fuel-cell-powered production vehicles? Meanwhile, chassis technology offers its own fascinations, and is fundamental to the application of any engine type. The menu is, fortunately, endless.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue