A thousand phone calls

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

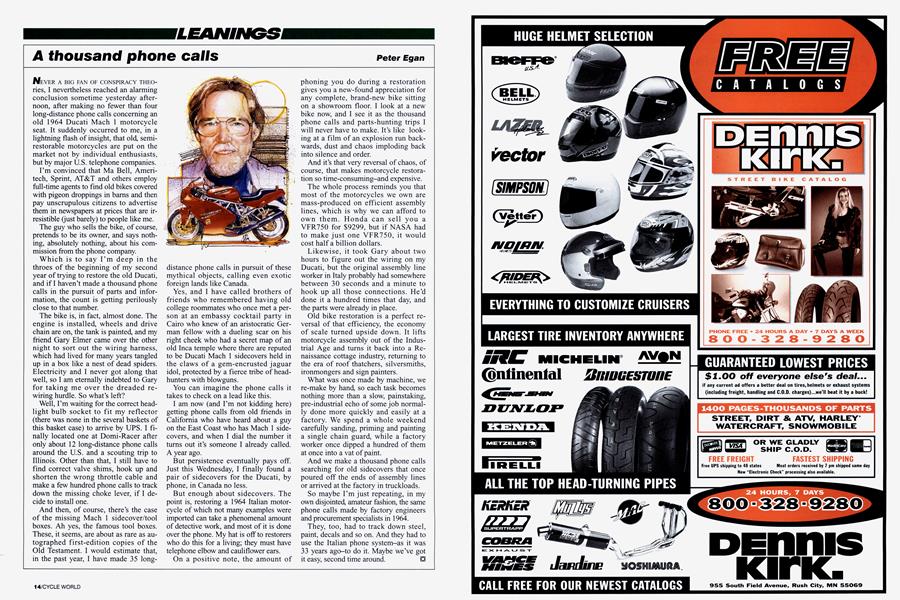

NEVER A BIG FAN OF CONSPIRACY THEOries, I nevertheless reached an alarming conclusion sometime yesterday afternoon, after making no fewer than four long-distance phone calls concerning an old 1964 Ducati Mach 1 motorcycle seat. It suddenly occurred to me, in a lightning flash of insight, that old, semirestorable motorcycles are put on the market not by individual enthusiasts, but by major U.S. telephone companies.

I’m convinced that Ma Bell, Ameritech, Sprint, AT&T and others employ full-time agents to find old bikes covered with pigeon droppings in bams and then pay unscrupulous citizens to advertise them in newspapers at prices that are irresistible (just barely) to people like me.

The guy who sells the bike, of course, pretends to be its owner, and says nothing, absolutely nothing, about his commission from the phone company.

Which is to say I’m deep in the throes of the beginning of my second year of trying to restore the old Ducati, and if I haven’t made a thousand phone calls in the pursuit of parts and information, the count is getting perilously close to that number.

The bike is, in fact, almost done. The engine is installed, wheels and drive chain are on, the tank is painted, and my friend Gary Elmer came over the other night to sort out the wiring harness, which had lived for many years tangled up in a box like a nest of dead spiders. Electricity and I never got along that well, so I am eternally indebted to Gary for taking me over the dreaded rewiring hurdle. So what’s left?

Well, I’m waiting for the correct headlight bulb socket to fit my reflector (there was none in the several baskets of this basket case) to arrive by UPS. I finally located one at Domi-Racer after only about 12 long-distance phone calls around the U.S. and a scouting trip to Illinois. Other than that, I still have to find correct valve shims, hook up and shorten the wrong throttle cable and make a few hundred phone calls to track down the missing choke lever, if I decide to install one.

And then, of course, there’s the case of the missing Mach 1 sidecover/tool boxes. Ah yes, the famous tool boxes. These, it seems, are about as rare as autographed first-edition copies of the Old Testament. I would estimate that, in the past year, I have made 35 longdistance phone calls in pursuit of these mythical objects, calling even exotic foreign lands like Canada.

Yes, and I have called brothers of friends who remembered having old college roommates who once met a person at an embassy cocktail party in Cairo who knew of an aristocratic German fellow with a dueling scar on his right cheek who had a secret map of an old Inca temple where there are reputed to be Ducati Mach 1 sidecovers held in the claws of a gem-encrusted jaguar idol, protected by a fierce tribe of headhunters with blowguns.

You can imagine the phone calls it takes to check on a lead like this.

I am now (and I’m not kidding here) getting phone calls from old friends in California who have heard about a guy on the East Coast who has Mach 1 sidecovers, and when I dial the number it turns out it’s someone I already called. A year ago.

But persistence eventually pays off. Just this Wednesday, I finally found a pair of sidecovers for the Ducati, by phone, in Canada no less.

But enough about sidecovers. The point is, restoring a 1964 Italian motorcycle of which not many examples were imported can take a phenomenal amount of detective work, and most of it is done over the phone. My hat is off to restorers who do this for a living; they must have telephone elbow and cauliflower ears.

On a positive note, the amount of phoning you do during a restoration gives you a new-found appreciation for any complete, brand-new bike sitting on a showroom floor. I look at a new bike now, and I see it as the thousand phone calls and parts-hunting trips I will never have to make. It’s like looking at a film of an explosion run backwards, dust and chaos imploding back into silence and order.

And it’s that very reversal of chaos, of course, that makes motorcycle restoration so time-consuming-and expensive.

The whole process reminds you that most of the motorcycles we own are mass-produced on efficient assembly lines, which is why we can afford to own them. Honda can sell you a VFR750 for $9299, but if NASA had to make just one VFR750, it would cost half a billion dollars.

Likewise, it took Gary about two hours to figure out the wiring on my Ducati, but the original assembly line worker in Italy probably had somewhere between 30 seconds and a minute to hook up all those connections. He’d done it a hundred times that day, and the parts were already in place.

Old bike restoration is a perfect reversal of that efficiency, the economy of scale turned upside down. It lifts motorcycle assembly out of the Industrial Age and turns it back into a Renaissance cottage industry, returning to the era of roof thatchers, silversmiths, ironmongers and sign painters.

What was once made by machine, we re-make by hand, so each task becomes nothing more than a slow, painstaking, pre-industrial echo of some job normally done more quickly and easily at a factory. We spend a whole weekend carefully sanding, priming and painting a single chain guard, while a factory worker once dipped a hundred of them at once into a vat of paint.

And we make a thousand phone calls searching for old sidecovers that once poured off the ends of assembly lines or arrived at the factory in truckloads.

So maybe I’m just repeating, in my own disjointed, amateur fashion, the same phone calls made by factory engineers and procurement specialists in 1964.

They, too, had to track down steel, paint, decals and so on. And they had to use the Italian phone system-as it was 33 years ago-to do it. Maybe we’ve got it easy, second time around.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue