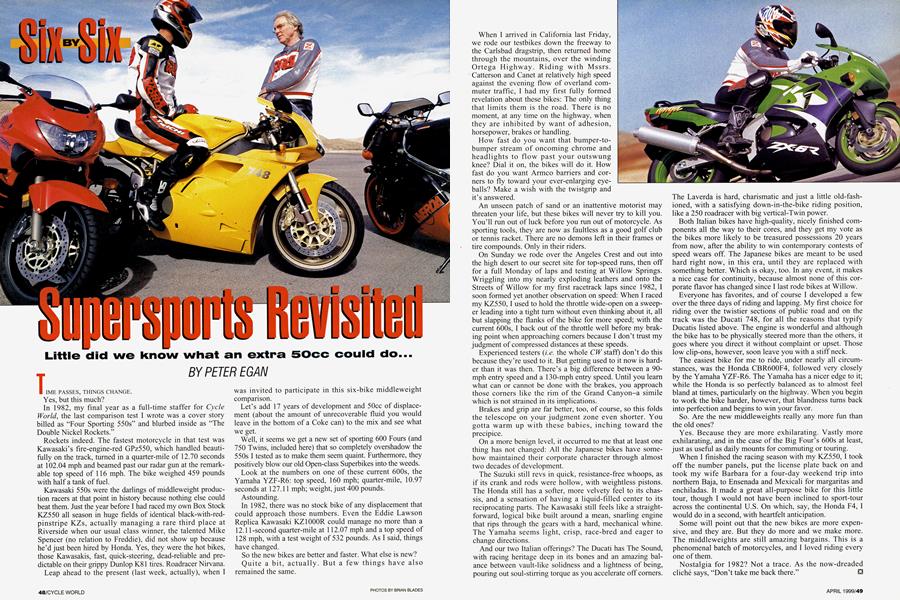

Supersports Revisited

SixBYSix

Little did we know what an extra 50cc could do...

PETER EGAN

TIME PASSES, THINGS CHANGE. Yes, but this much? In 1982, my final year as a full-time staffer for Cycle World, the last comparison test I wrote was a cover story billed as "Four Sporting 550s" and blurbed inside as "The Double Nickel Rockets."

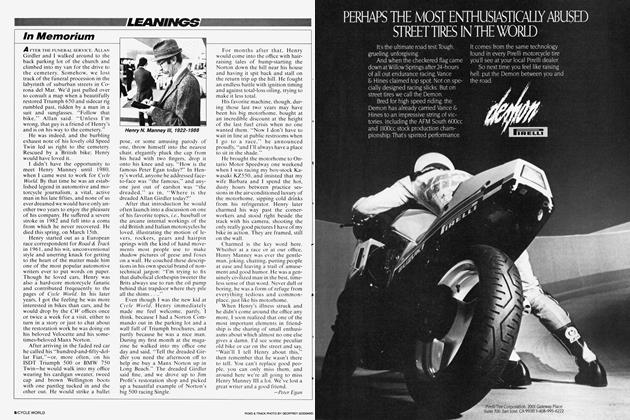

Rockets indeed. The fastest motorcycle in that test was Kawasaki's fire-engine-red GPz550, which handled beautifully on the track, turned in a quarter-mile of 12.70 seconds at 102.04 mph and beamed past our radar gun at the remarkable top speed of 116 mph. The bike weighed 459 pounds with half a tank of fuel. Kawasaki 550s were the darlings of middleweight production racers at that point in history because nothing else could beat them. Just the year before I had raced my own Box Stock KZ550 all season in huge fields of identical black-with-redpinstripe KZs, actually managing a rare third place at Riverside when our usual class winner, the talented Mike Spencer (no relation to Freddie), did not show up because he'd just been hired by Honda. Yes, they were the hot bikes, those Kawasakis, fast, quick-steering, dead-reliable and predictable on their grippy Dunlop K81 tires. Roadracer Nirvana. Leap ahead to the present (last week, actually), when I

was invited to participate in this six-bike middleweight comparison. Let's add 17 years of development and 50cc of displacement (about the amount of unrecoverable fluid you would leave in the bottom of a Coke can) to the mix and see what we get.

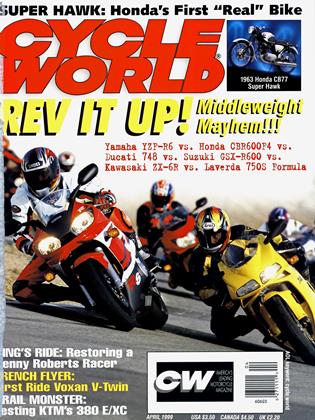

Well, it seems we get a new set of sporting 600 Fours (and 750 Twins, included here) that so completely overshadow the 550s I tested as to make them seem quaint. Furthermore, they positively blow our old Open-class Superbikes into the weeds. Look at the numbers on one of these current 600s, the Yamaha YZF-R6: top speed, 160 mph; quarter-mile, 10.97 seconds at 127.11 mph; weight, just 400 pounds. Astounding. In 1982, there was no stock bike of any displacement that could approach those numbers. Even the Eddie Lawson Replica Kawasaki KZ1000R could manage no more than a 12.11-second quarter-mile at 112.07 mph and a top speed of 128 mph, with a test weight of 532 pounds. As I said, things have changed. So the new bikes are better and faster. What else is new? Quite a bit, actually. But a few things have also remained the same.

When I arrived in California last Friday, we rode our testbikes down the freeway to the Carlsbad dragstrip, then returned home through the mountains, over the winding Ortega Highway. Riding with Mssrs.

Catterson and Canet at relatively high speed against the evening flow of overland commuter traffic, I had my first fully formed revelation about these bikes: The only thing that limits them is the road. There is no moment, at any time on the highway, when they are inhibited by want of adhesion, horsepower, brakes or handling.

How fast do you want that bumper-tobumper stream of oncoming chrome and headlights to flow past your outswung knee? Dial it on, the bikes will do it. How fast do you want Armco barriers and corners to fly toward your ever-enlarging eyeballs? Make a wish with the twistgrip and it’s answered.

An unseen patch of sand or an inattentive motorist may threaten your life, but these bikes will never try to kill you. You’ll run out of luck before you run out of motorcycle. As sporting tools, they are now as faultless as a good golf club or tennis racket. There are no demons left in their frames or tire compounds. Only in their riders.

On Sunday we rode over the Angeles Crest and out into the high desert to our secret site for top-speed runs, then off for a full Monday of laps and testing at Willow Springs. Wriggling into my nearly exploding leathers and onto the Streets of Willow for my first racetrack laps since 1982, I soon formed yet another observation on speed: When I raced my KZ550,1 used to hold the throttle wide-open on a sweeper leading into a tight turn without even thinking about it, all but slapping the flanks of the bike for more speed; with the current 600s, I back out of the throttle well before my braking point when approaching comers because I don’t tmst my judgment of compressed distances at these speeds.

Experienced testers (i.e. the whole CW staff) don’t do this because they’re used to it. But getting used to it now is harder than it was then. There’s a big difference between a 90mph entry speed and a 130-mph entry speed. Until you leam what can or cannot be done with the brakes, you approach those corners like the rim of the Grand Canyon-a simile which is not strained in its implications.

Brakes and grip are far better, too, of course, so this folds the telescope on your judgment zone even shorter. You gotta warm up with these babies, inching toward the precipice.

On a more benign level, it occurred to me that at least one thing has not changed: All the Japanese bikes have somehow maintained their corporate character through almost two decades of development.

The Suzuki still revs in quick, resistance-free whoops, as if its crank and rods were hollow, with weightless pistons. The Honda still has a softer, more velvety feel to its chassis, and a sensation of having a liquid-filled center to its reciprocating parts. The Kawasaki still feels like a straightforward, logical bike built around a mean, snarling engine that rips through the gears with a hard, mechanical whine. The Yamaha seems light, crisp, race-bred and eager to change directions.

And our two Italian offerings? The Ducati has The Sound, with racing heritage deep in its bones and an amazing balance between vault-like solidness and a lightness of being, pouring out soul-stirring torque as you accelerate off comers.

The Laverda is hard, charismatic and just a little old-fashioned, with a satisfying down-in-the-bike riding position, like a 250 roadracer with big vertical-Twin power.

Both Italian bikes have high-quality, nicely finished components all the way to their cores, and they get my vote as the bikes more likely to be treasured possessions 20 years from now, after the ability to win contemporary contests of speed wears off. The Japanese bikes are meant to be used hard right now, in this era, until they are replaced with something better. Which is okay, too. In any event, it makes a nice case for continuity, because almost none of this corporate flavor has changed since I last rode bikes at Willow.

Everyone has favorites, and of course I developed a few over the three days of riding and lapping. My first choice for riding over the twistier sections of public road and on the track was the Ducati 748, for all the reasons that typify Ducatis listed above. The engine is wonderful and although the bike has to be physically steered more than the others, it goes where you direct it without complaint or upset. Those low clip-ons, however, soon leave you with a stiff neck.

The easiest bike for me to ride, under nearly all circumstances, was the Honda CBR600F4, followed very closely by the Yamaha YZF-R6. The Yamaha has a nicer edge to it; while the Honda is so perfectly balanced as to almost feel bland at times, particularly on the highway. When you begin to work the bike harder, however, that blandness turns back into perfection and begins to win your favor.

So. Are the new middleweights really any more fun than the old ones?

Yes. Because they are more exhilarating. Vastly more exhilarating, and in the case of the Big Four’s 600s at least, just as useful as daily mounts for commuting or touring.

When I finished the racing season with my KZ550, I took off the number panels, put the license plate back on and took my wife Barbara for a four-day weekend trip into northern Baja, to Ensenada and Mexicali for margaritas and enchiladas. It made a great all-purpose bike for this little tour, though I would not have been inclined to sport-tour across the continental U.S. On which, say, the Honda F4, I would do in a second, with heartfelt anticipation.

Some will point out that the new bikes are more expensive, and they are. But they do more and we make more. The middleweights are still amazing bargains. This is a phenomenal batch of motorcycles, and I loved riding every one of them.

Nostalgia for 1982? Not a trace. As the now-dreaded cliché says, “Don’t take me back there.” □