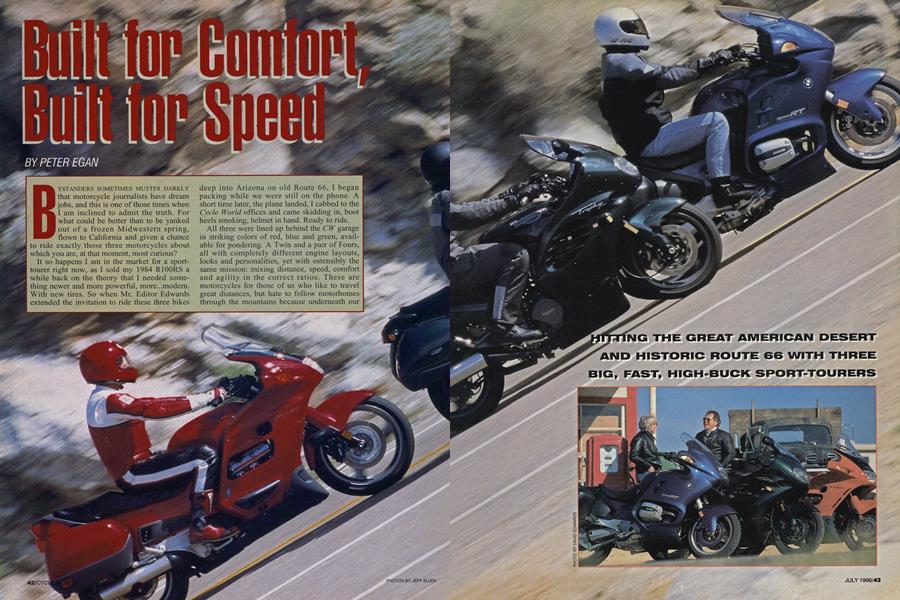

Built for Comfort, Built for Speed

PETER EGAN

BYSTANDERS SOMETIMES MUTTER DARKLY that motorcycle journalists have dream jobs, and this is one of those times when I am inclined to admit the truth. For what could be better than to be yanked out of a frozen Midwestern spring, flown to California and given a chance to ride exactly those three motorcycles about which you are, at that moment, most curious?

It so happens I am in the market for a sporttourer right now, as I sold my 1984 R100RS a while back on the theory that I needed something newer and more powerful, more...modem. With new tires. So when Mr. Editor Edwards extended the invitation to ride these three bikes deep into Arizona on old Route 66, I began packing while we were still on the phone. A short time later, the plane landed, I cabbed to the Cycle World offices and came skidding in, boot heels smoking, helmet in hand. Ready to ride.

All three were lined up behind the CW garage in striking colors of red, blue and green, available for pondering. A Twin and a pair of Fours, all with completely different engine layouts, looks and personalities, yet with ostensibly the same mission: mixing distance, speed, comfort and agility in the correct ratios. These are motorcycles for those of us who like to travel great distances, but hate to follow motorhomes through the mountains because underneath our mature, thoughtful exteriors we have the same long-suffering patience as rabid bats in a bam fire.

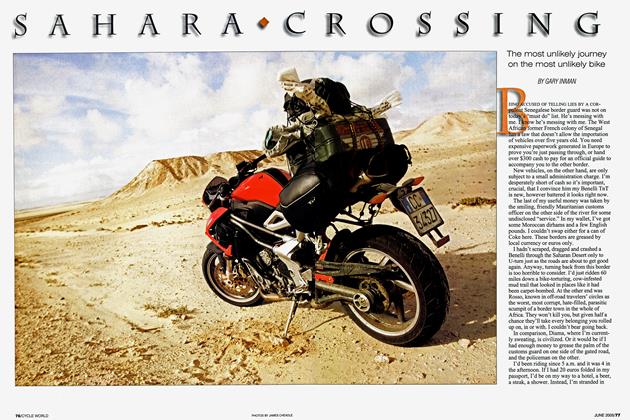

HITTING THE GREAT AMERICAN DESERT AND HISTORIC ROUTE 66 WITH THREE BIG, FAST, HIGH-BUCK SPORT-TOURERS

BMW R1100RT

Since selling my old RIOORS, I’ve held off on buying a new or used RI 100RS because, although the new RS does almost everything better (except be simple and cheap), its weather protection is not as good as the old Beemer’s. Perhaps, I reasoned, the new RT would split the difference and be sportier than the old RT while delivering the weather protection of the old RS. And maybe the windshield would not put out a deafening, sense-addling level of wind noise and helmet roar like my old RS’s did.

Well. When the new RT arrived, I was somewhat taken aback by its aero-egg styling, high price, non-optional radio and apparent bulk. Sitting next to it in the local dealership, the last of the old-generation BMW R1 OORTs looks almost delicate. Also relatively inexpensive, easy to maintain and simple as a dirtbike; essentially, everything the new RT is not.

On the other hand, the new RT’s styling looks good from some angles (and will probably continue to grow on me), and staffers who rode the bike back from its Montana press introduction gave it rave reviews, saying it just plain works. And, having spent considerable time on the more lithe RI 100RS, I am favorably disposed toward BMW’s remarkable compliant-yet-planted Telelever front suspension, nonkneeling Paralever rear suspension (many levers here) and superb ABS-equipped brakes.

Also, the new-generation, fuel-injected, cam-in-head engine maintains its Boxer heritage while putting out 82 silken horsepower at 7250 rpm and 75 foot-pounds of torque at 5750 rpm, a big improvement on the old one-liter Boxer motor, which can feel a bit chuffy and strained by comparison. The whole bike is a reasonably convincing argument for The Future.

Obviously, a long ride on some famous highway was needed to see if the RS virtues transferred, undiminished, to the RT.

HONDA ST1100 ABS II

Honda’s sport-tourer has been around since the 1991 model year and has won Cycle World's Best Touring Bike award four years in a row. I rode the very first testbike up the Pacific Coast Highway to the USGP at Laguna Seca in the summer of 1990, two-up, and was impressed with the ST’s mellifluous, torquey motor, tall and easy gearing, vast range, comfort, all-around refinement and-most of all—that the bike could be ridden so quickly and effortlessly in the company of pure sportbikes. For a 702-pound motorcycle, fully fueled, it was (and still is) an amazingly deft backroad companion.

Wind flow around the screen, however, was a little noisy, and if you added a passenger the wind mysteriously ran straight down your back (and the passenger’s front) like a bad curve in the Canadian jetstream. Cold.

Since 1992, the ST has been available in two versions, the standard non-ABS model or with ABS and TCS (traction control) for a few grand extra. This year there is still a standard model for $11,599, or our $13,999 ABS II-TCS version, now with the mixed blessings of a Linked Braking System, as first seen on the CBR1000F. More on this later. The ST also has a new windscreen with pressure-relief holes for quieter flow and better weather protection. And a higher output alternator, boosted from 18 to 40 amps.

Beneath these updates is the same punchy 1084cc longitudinal V-Four with four belt-driven cams, liquid cooling and an output of 96 rear-wheel horsepower at 7250 rpm and 78 foot-pounds of torque at 6000 rpm. It also has stout 43mm fork legs with Honda’s TRAC (Torque Reactive Anti-dive Control) system, adjustable single-shock rear suspension and an enormous 7.4-gallon gas tank. This year, the ABS II version of the STI 100 also gets new radial tires, which may reduce a front tire cupping problem highermileage STs have had in the past.

TRIUMPH TROPHY 1200

Least radical of the group, the Triumph is basic motorcycle, a big powerful warhorse that generally follows the longsuccessful UJM layout: transverse four-cylinder twin-cam engine and chain drive, but with a fully adjustable single shock at the rear. When Triumph decided to go after the sport-touring buyer, it left the spine frame and driveline alone but restyled the bodywork with rounder curves and Ford Taurus-like dual headlights, while adding a pair of large, 32-liter Givi-built hard plastic saddlebags.

Ergonomics were also fiddled with for more long-distance comfort-higher, more pulled-back handlebars, repositioned footpegs and a new seat were stirred into the mix. Interestingly, while it “sits” big and tall, the Triumph is the lightest of our three bikes, and its 58.7-inch wheelbase is only 0.3 inch longer than the BMW’s and 2.5 inches shorter than the Honda’s.

I rode the old Trophy 1200 through New Zealand last year and found it a fast, competent bike with stable and accurate, if not inspired, handling, lacking only real luggage to make it what perhaps it should have been all along-a sport-tourer to compete with the other two bikes in this test.

ON THE ROAD

Dry morning warmth and beaming sunlight, the kind that reacts with black leather and makes you feel good to the bone. We fill up the bikes and run counter-commute out of Orange County and into the desert, past the old Riverside racetrack where now the Moreno Valley Shopping Mall proudly stands. Seems we had too many racetracks and not enough places to buy overpriced athletic shoes.

Up through Banning Pass, past the wind generators near Palm Springs and off on the little roads toward Joshua Tree and Amboy, onto Historic Route 66. This is the desert country beloved of ad agencies, where faded convertibles mingle with biker gangs, ghost-town saloons and miraculously cold beer that makes it snow. I am riding the Triumph.

Let me say this about the Triumph: It has power.

And not just at the upper end. The engine is like the offspring of a liaison between an Open-class endurance bike and a Farmall tractor. You can motor through the town of Yucca Valley at 30 mph in top gear (sixth) without a hint of stumble, ping or shudder. Yet out on the highway, passing cars and trucks, it all but flattens your nose and jowls in waves of effortless acceleration.

Following Jon Thompson on the BMW and Edwards on the Honda, I find myself playing an acceleration game for my own amusement: I give them a long lead when we move out to pass a car, then dial on the throttle at the last minute, closing the gap between our bikes like an arrow fired from a longbow, piling on the brakes to avoid a rear-end collision. And this in top gear. No downshift needed.

The other two bikes feel (and are) plenty quick, but the Triumph has a definite edge when throttles are suddenly twisted to take advantage of a gap in traffic. The 1200 Four doesn’t have the soulful exhaust note of the 900 Triple, but it gets the job done right now. On the dyno, it has only about a 1-horsepower advantage on the Honda and slightly less peak torque, but its very broad torque spread, lower sixth gear and lighter weight make a difference.

In overall feel, the Trophy is slightly stiffer and more precise feeling than the other two bikes, more mechanical and less damped everywhere. Though the ride is very good, it is just a bit harsher and-a British bike enthusiast might tell you-more real. Full metal.

It is also the loudest, in terms of wind noise. I could have used the optional taller windscreen for my 6-foot, 1-inch frame, because, having forgotten my earplugs, I almost went deaf riding the Triumph. The seat is moderately comfortable, but quite narrow at the front and tilted slightly forward. Also, the rather wide, tall handlebars keep you pinned to the rear of the rider’s section, so there’s not much flexibility of movement.

In mountain-road handling the Trophy feels long, stable and predictable. The handlebars give you a lot of leverage, but you need it because you have the sense of hustling a rather large motorcycle through the tight stuff, and feedback from the front tire is not as acute as with the other two bikes. It’ll get through the curves just as fast, but without the same sense of ease and confidence you get from the Honda or BMW.

Nice roomy saddlebags, easily unlocked and removed, good finish, handsome instrumentation; an honest, straightahead bike without a lot of frills, senseless or otherwise.

We trade bikes at Amboy, on old Route 66, at a historic stainless-steel-festooned diner called Roy’s, which is closing as we arrive. They let us in, nevertheless, to soak up a little air-conditioned shade and a few gallons of water and soft drinks. From there through the afternoon, I ride the BMW RI 100RT.

My first reaction to the BMW is that it has a lot of nooks, crannies, ducts, speaker grilles, knobs and doo-dads after the clean, simple Triumph. In true BMW tradition, however, a lot of them do something for you. And some don’t.

The electrically controlled windshield does. A thumb switch on the left handlebar moves it through 20 degrees of rake. Full-up, it makes the wind flow around your shoulders and leaves your helmet dead calm and silent-the only one of our bikes with this golden feature. As it moves downward, you get increasing levels of wind noise and ventilation. In some of the very hot weather we rode through, the UP position is simply too warm, so you have to trade some noise for fresh air.

In cool weather it’s great. And so are the standard-equipment heated handgrips, which Editor Edwards remarked ought to be required by law on any touring bike, and I agree. Not so effective are some little fairing ducts that, when opened, channel warm air from the oil cooler to your hands. The faint heat seems to lose its way, but I suppose every little bit helps when the cold turns grim.

Somewhat wasted on our staff of experts was the radio, which no one thought loud or clear enough to overcome the wind and bike noise. My own tendency is to avoid running loud motors while listening to my home stereo system, and vice versa. Each seems to cancel out the soul-soothing benefits of the other, like industrial white noise. But to each his or her own.

BMW’s three-position adjustable seat is a good idea, however. In the lowest position I feel like an alumnus visiting his third-grade desk, but the highest is just right. The beautifully polished handlebars keep you in just a slight forward lean, but also fix you pretty firmly at the rear of the rider’s seat, which is a little wider and more comfortable than the Triumph’s, but still has a forward tilt and forces you to push away from the tank periodically, or stand up to rearrange your Jockey shorts.

Why bike manufacturers don’t quit screwing around and just copy the flat, wide, long comfortable seat on the 1980 Suzuki GS1000 is beyond me. But they don’t. And Mike Corbin loves them for it.

On the road, the BMW’s suspension soaks up bumps and dips with aplomb. Both ends stay firmly connected to the road, but are compliant and never harsh. It’s wonderful to watch the action of that stiction-free Telelever front end as it soaks up a thousand small irregularities without upsetting the bike. The front end also works brilliantly under braking, with the RT’s powerful front discs inducing just enough drop to give the bike a settled feel, but not so much that it actually dives.

We did three or four passes, up and downhill, on a divided, curving stretch of steep mountain road, and all three of us voted the RI 100RT King of the Mountain. Of our three bikes, it is the most confidence-inspiring at speed, has the best and most easily modulated brakes, and gives the rider the greatest sense of feedback from its tires. We rated the Honda a close second on this section and the Triumph a nottoo-distant third.

The only glitch with the BMW was a tendency, under steady uphill throttle, to surge slightly as if the fuel injection were hunting for the correct mixture. Our primitive carbureted Honda and Triumph ran flawlessly. Ah, progress.

Back and forth we traded the bikes, stopping for the night in the created-from-nothing gambling mecca of Laughlin, Nevada, on the Colorado River, where we lodged in a glitzy casino the size of Rhode Island. David pointed out that gamblers never look like they’re having much fun, and I had to admit he was right. A hard-smoking woman at a nearby slot machine wore the expression of someone sniffing a quart of milk that’s been in the refrigerator a week too long.

In the morning, I rode the Honda through Kingman, onto old 66 again and then south toward Prescott, Arizona.

You don’t have to ride the Honda ST 1100 long to see why it’s won Touring Bike of the Year so many times. It has a deep, purring exhaust note, a longish wide seat, a powerful engine that’s nearly as much of a stump puller as the Triumph’s and tall gearing that allows it to cruise at a relaxed 3450 rpm at 70 mph. Among our three bikes, it also has the sportiest riding position, canting the rider forward into a comfortable tuck, while allowing considerable movement on the seat. Ride quality was pretty mushy until we dialed in more rear shock damping, and then it tightened up to within a hairsbreadth of the BMW’s superb road manners.

Curiously, though the Honda is both the heaviest and longest-wheelbased bike in the group, it feels smaller on the road than either the BMW or Triumph. Low seat height may have something to do with it-it’s about 2 inches lower than the Trophy’s and just a little above the BMW’s lowest adjusted position-combined with bar and peg placement. Or it may just be the compact cleanness of the fairing. Only in very slow maneuvers do you feel the Honda’s true porkitude, though all these bikes become suddenly hulkish when you have to move them around a parking lot.

Incidentally, I clumsily dropped the Honda in just such a parking maneuver (blaming my bad back, as there was no one else around). It landed on its fairing tip-over bumper and knocked off the left mirror. We picked it up (notice I do not say / picked it up), reattached the mirror with its clever plug-in snaps and found no sign of damage anywhere on the bike. I like that.

The new windshield is only semi-quiet for the tall rider-better than the Triumph, but not as silent as the BMW on full upward tilt. It needs to be just a shade taller for me. When I retracted my neck an inch or two, all was serene and silent. Still, not a bad compromise between noise, fresh air and aerodynamics.

Only one unpleasant characteristic plagued us with the Honda throughout the trip: the Linked Braking System.

This setup, which allows the rear pedal to engage a pair of front-brake pistons (there are six), and the front lever to activate a limited amount of rear brake, is quite effective in a straight-ahead panic stop; the Honda hauls its considerable weight down fiercely. It is also a good system for beginning riders who are shy of the front brake, especially in emergencies.

But ST 1 100 buyers are very seldom beginning riders. And what the experienced rider notices most is that the brakes are (a) overly sensitive and touchy, and (b) that trailing a small amount of rear brake into a comer to settle the

bike causes the front end to grab and dive, throwing your rhythm off. Unsettling. The rear pedal also activates the front discs in slow gas-station maneuvers, while you have the front fork cocked, upsetting your balance and increasing your odds of dropping the bike.

Essentially, this system makes the bike a little safer in straight panic stops (though the excellent ABS is more significant here), but takes much fun out of riding a mountain road, a mission for which the ST1100 is otherwise admirably suited. This is a confidence-inspiring, fine-handling bike, but the LBS system never gives you what you want, when you want it.

Would that it could be disengaged with a simple push of a button, like the Traction Control. Better yet, would that it were not there at all. Sadly, you can’t get ABS in the ST 1100 without the LBS.

Other nits to pick? The Honda’s broad, spacious seat seems to settle as the hours drone on, losing its shape and composure. One grade firmer foam might do it. Frankly, I would toss every one of these seats and go aftermarket before leaving on a long trip.

And a fine long trip we had. Spent the night in Prescott at the wonderful old restored Hassayampa Hotel, right on the square, drinking and dining like the true Western cattlemen we are, under all this riding gear, then rode home on one long, fast day, dropping from mountains to desert floor on Highway 89, across the Colorado at Parker, down a few more segments of old 66, over the hump at Banning and down into the green hanging gardens of Babylon otherwise known as greater L.A. Home at sundown.

At a last iced-tea tankup, I asked my two colleagues which bike they would pick for the duration if we had to turn around right now and head for New York. After some thought, both said, “Probably the BMW.” “Why?”

said Edwards. “The windshield, heated grips, plug-in for electric vest, standard luggage rack...so on. You pay more for the BMW ($15,990), but they give you a lot; you don’t have to buy many extras. They thought of nearly everything.” We were unanimous in agreeing that the BMW was the best-handling bike on a winding road, and also had the best ride.

Second pick, and my first, was the ST 1100. Why? Almost for the reverse of the BMW’s appeal; simplicity versus options and clutter. As Thompson said, “Except for the wonderful sound of the engine, the Honda almost becomes invisible when you ride it. I mean that in a positive sense; it works so well, there are no irritants or distractions between you and the scenery or the road-except for the brakes, of course.”

The Honda was also mileage and range champ of the group, averaging 41.9 mpg, giving its 7.4-gallon tank a remarkable range of 310 miles to empty. Ridden in a medium cruise mode, the Honda got closer to 50 mpg. The BMW was a very close second, at 40.4 mpg, but its smaller, 6.6-gallon tank brought its range down to a still respectable 267 miles. On the Triumph, you pay for all that roll-on horsepower with a 33.9 mpg average and a range of 223 miles on its 6.6-gallon tank. On the road, the Trophy hit reserve at around 175 miles, while the Honda gauge hovered at half-full.

The Triumph was third pick for all of us, but not by much. Not as refined as the other two, it is nevertheless a noble beast for swooping across great expanses of America, and its engine never fails to delight. I, personally, would need only a quieter windshield, slightly lower bars and a better seat to warm up to the Triumph-and maybe the charismatic rip of the 900 Triple engine, at the expense of that vast well of horsepower.

When we got back to the office that evening, deep in satisfied fatigue, ears ringing, I needed to borrow a bike to ride to my sister Barbara’s house, where I would be staying for the night, half an hour away.

I transferred my riding gear to the saddlebags of the Honda, even though I’d been on the ST for the past three hours, hammering across the desert, then dodging and darting through freeway traffic. I guess this is called voting with your luggage.

Maybe I’ll look for a non-LBS version, or a good used one. Honda’s ABS is fine, without the Linked Braking System. The hardest pill for me to swallow in considering an ST 1100 is its unfortunate familial resemblance to the Pacific Coast 800-1 like bare handlebars much better than gooshy plastic handlebar covers, for instance-but the bike works so well I almost don’t care. The sound and pull of that V-Four, the sense of a solid billet chassis with a liquidfilled center, the great riding position, all win me over.

But I haven’t ruled out the lighter, nimbler BMW RI 100RS, either (the RT is just too bulky and expensive for my tastes). Or a 900 Trophy. Or another old BMW Boxer for $2000. Or that Guzzi 1000S I’ve never owned. Great bikes, all.

So I guess I’m still shopping.

Hard to beat the Honda, though. I felt happy every time I got on it, and it’s this quiet, highly personal glow of satisfaction that makes a motorcycle worth having and keeping.

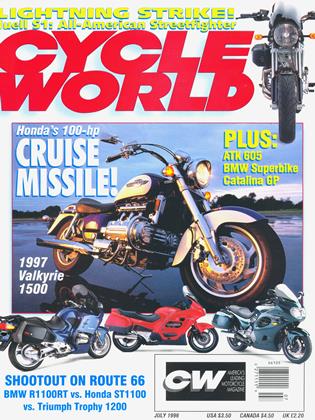

BMW

R1100RT

$15,990

HONDA

ST1100 ABS II

$13,999

TRIUMPH

TROPHY 1200

$12,995

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontNorton Boy

July 1996 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsTriumph Deferment

July 1996 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCIntake Flow 101

July 1996 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1996 -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Superbike Revival

July 1996 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupIs There A Stroker In Your Future?

July 1996 By Kevin Cameron