Forever young

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

WHILE DRIVING THROUGH A LIGHT snowstorm to see my dad at the nursing home this weekend, I happened to be listening to A Prairie Home Companion with Garrison Keillor on the radio.

For those of you who are unfamiliar with this program, it's a variety show broadcast live from St. Paul on National Public Radio, generally highlighting humorists and musicians whose work is not tedious enough to land them a slot on Easy Listening stations. It often features blues, Cajun, bluegrass, folk and genuine country music. My kind of stuff: Hard Listening.

Anyway, at one point in the show, host Keillor sang one of the great old Bob Dylan songs, “Forever Young.” He sang it with a clear, moving simplicity that made it sound almost like a traditional church hymn.

Which I guess it would be natural to do. It’s written almost as a psalm or a prayer anyway, each verse ending with the wish, “May you stay forever young...”

I have to admit, it made me feel pretty sad. I was going to visit my father, who remains cheerful, with a sharp sense of humor, but cannot remember being in the Navy during WWII, nor where his children now live. He can’t remember owning his ’66 Mustang, either.

He’s forever young in some waysmostly in his easy wit and our family’s recollections-but not in other ways. Time marches on. Even Bob Dylan himself is not looking like a kid these days. It’s mostly his music that keeps him fixed in time.

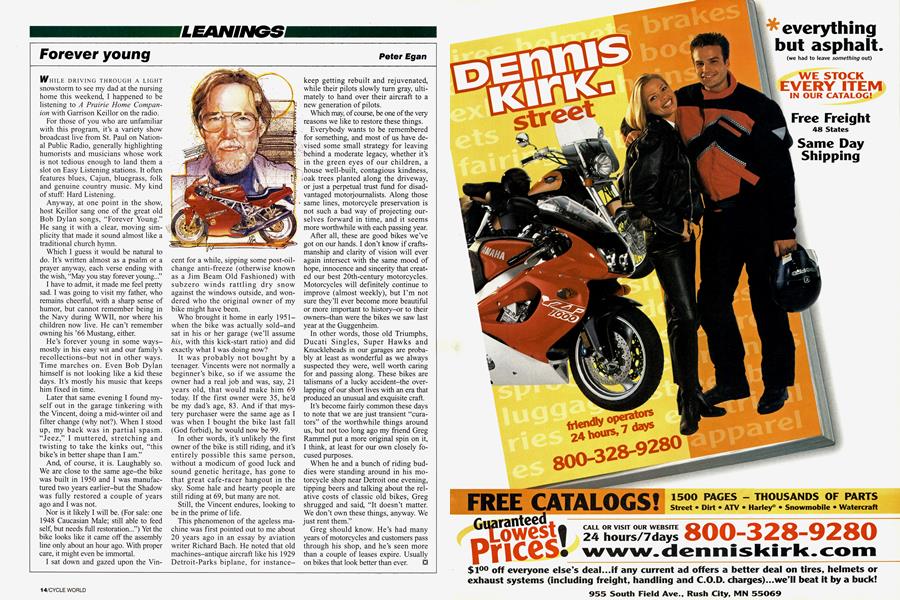

Later that same evening I found myself out in the garage tinkering with the Vincent, doing a mid-winter oil and filter change (why not?). When I stood up, my back was in partial spasm. “Jeez,” I muttered, stretching and twisting to take the kinks out, “this bike’s in better shape than I am.”

And, of course, it is. Laughably so. We are close to the same age-the bike was built in 1950 and I was manufactured two years earlier-but the Shadow was fully restored a couple of years ago and I was not.

Nor is it likely I will be. (For sale: one 1948 Caucasian Male; still able to feed self, but needs full restoration...”) Yet the bike looks like it came off the assembly line only about an hour ago. With proper care, it might even be immortal.

I sat down and gazed upon the Vincent for a while, sipping some post-oilchange anti-freeze (otherwise known as a Jim Beam Old Fashioned) with subzero winds rattling dry snow against the windows outside, and wondered who the original owner of my bike might have been.

Who brought it home in early 1951when the bike was actually sold-and sat in his or her garage (we’ll assume his, with this kick-start ratio) and did exactly what I was doing now?

It was probably not bought by a teenager. Vincents were not normally a beginner’s bike, so if we assume the owner had a real job and was, say, 21 years old, that would make him 69 today. If the first owner were 35, he’d be my dad’s age, 83. And if that mystery purchaser were the same age as I was when I bought the bike last fall (God forbid), he would now be 99.

In other words, it’s unlikely the first owner of the bike is still riding, and it’s entirely possible this same person, without a modicum of good luck and sound genetic heritage, has gone to that great cafe-racer hangout in the sky. Some hale and hearty people are still riding at 69, but many are not.

Still, the Vincent endures, looking to be in the prime of life.

This phenomenon of the ageless machine was first pointed out to me about 20 years ago in an essay by aviation writer Richard Bach. He noted that old machines-antique aircraft like his 1929 Detroit-Parks biplane, for instance-

keep getting rebuilt and rejuvenated, while their pilots slowly turn gray, ultimately to hand over their aircraft to a new generation of pilots.

Which may, of course, be one of the very reasons we like to restore these things.

. Everybody wants to be remembered for something, and most of us have devised some small strategy for leaving behind a moderate legacy, whether it’s in the green eyes of our children, a house well-built, contagious kindness, joak trees planted along the driveway, or just a perpetual trust fund for disadvantaged motorjournalists. Along those same lines, motorcycle preservation is not such a bad way of projecting ourselves forward in time, and it seems more worthwhile with each passing year.

After all, these are good bikes we’ve got on our hands. I don’t know if craftsmanship and clarity of vision will ever again intersect with the same mood of hope, innocence and sincerity that created our best 20th-century motorcycles. Motorcycles will definitely continue to improve (almost weekly), but I’m not sure they’ll ever become more beautiful or more important to history-or to their owners-than were the bikes we saw last year at the Guggenheim.

In other words, those old Triumphs, Ducati Singles, Super Hawks and Knuckleheads in our garages are probably at least as wonderful as we always suspected they were, well worth caring for and passing along. These bikes are talismans of a lucky accident-the overlapping of our short lives with an era that produced an unusual and exquisite craft.

It’s become fairly common these days to note that we are just transient “curators” of the worthwhile things around us, but not too long ago my friend Greg Rammel put a more original spin on it, I think, at least for our own closely focused purposes.

When he and a bunch of riding buddies were standing around in his motorcycle shop near Detroit one evening, tipping beers and talking about the relative costs of classic old bikes, Greg shrugged and said, “It doesn’t matter. We don’t own these things, anyway. We just rent them.”

Greg should know. He’s had many years of motorcycles and customers pass through his shop, and he’s seen more than a couple of leases expire. Usually on bikes that look better than ever. □