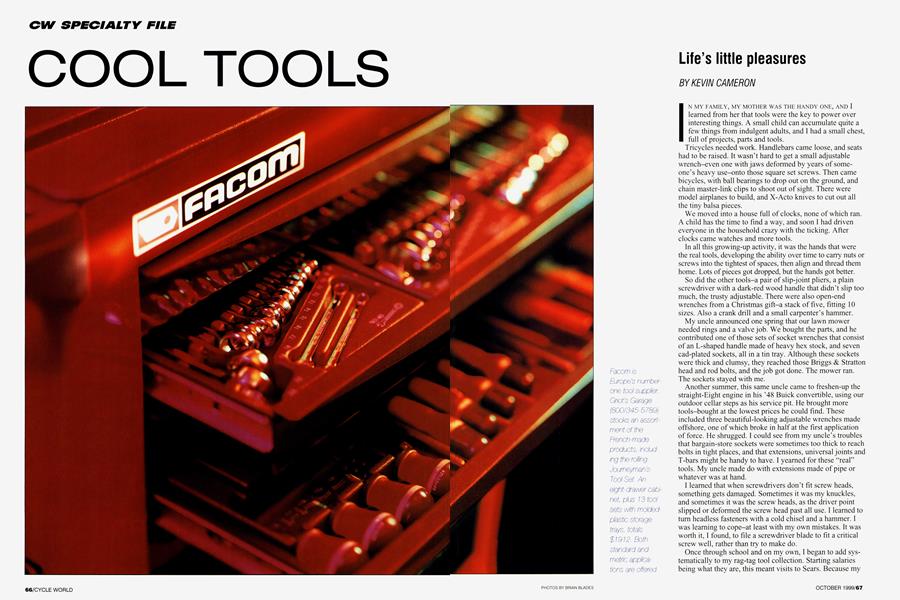

COOL TOOLS

CW SPECIALTY FILE

Life’s little pleasures

KEVIN CAMERON

IN MY FAMILY, MY MOTHER WAS THE HANDY ONE, AND I learned from her that tools were the key to power over interesting things. A small child can accumulate quite a few things from indulgent adults, and I had a small chest, full of projects, parts and tools.

Tricycles needed work. Handlebars came loose, and seats had to be raised. It wasn’t hard to get a small adjustable wrench—even one with jaws deformed by years of someone’s heavy use-onto those square set screws. Then came bicycles, with ball bearings to drop out on the ground, and chain master-link clips to shoot out of sight. There were model airplanes to build, and X-Acto knives to cut out all the tiny balsa pieces.

We moved into a house full of clocks, none of which ran. A child has the time to find a way, and soon I had driven everyone in the household crazy with the ticking. After clocks came watches and more tools.

In all this growing-up activity, it was the hands that were the real tools, developing the ability over time to carry nuts or screws into the tightest of spaces, then align and thread them home. Lots of pieces got dropped, but the hands got better.

So did the other tools-a pair of slip-joint pliers, a plain screwdriver with a dark-red wood handle that didn’t slip too much, the trusty adjustable. There were also open-end wrenches from a Christmas gift-a stack of five, fitting 10 sizes. Also a crank drill and a small carpenter’s hammer.

My uncle announced one spring that our lawn mower needed rings and a valve job. We bought the parts, and he contributed one of those sets of socket wrenches that consist of an L-shaped handle made of heavy hex stock, and seven cad-plated sockets, all in a tin tray. Although these sockets were thick and clumsy, they reached those Briggs & Stratton head and rod bolts, and the job got done. The mower ran. The sockets stayed with me.

Another summer, this same uncle came to freshen-up the Straight-Eight engine in his ’48 Buick convertible, using our outdoor cellar steps as his service pit. He brought more tools-bought at the lowest prices he could find. These included three beautiful-looking adjustable wrenches made offshore, one of which broke in half at the first application of force. He shrugged. I could see from my uncle’s troubles that bargain-store sockets were sometimes too thick to reach bolts in tight places, and that extensions, universal joints and T-bars might be handy to have. I yearned for these “real” tools. My uncle made do with extensions made of pipe or whatever was at hand.

I learned that when screwdrivers don’t fit screw heads, something gets damaged. Sometimes it was my knuckles, and sometimes it was the screw heads, as the driver point slipped or deformed the screw head past all use. I learned to turn headless fasteners with a cold chisel and a hammer. I was learning to cope-at least with my own mistakes. It was worth it, I found, to file a screwdriver blade to fit a critical screw well, rather than try to make do.

Once through school and on my own, I began to add systematically to my rag-tag tool collection. Starting salaries being what they are, this meant visits to Sears. Because my friends and I initially had British bikes, this meant Whitworth sizes. Then came metric. I wasn’t able to put up with that first socket set for long, and began to accumulate f2-inch drive. I soon found these large sockets more suitable to auto service, and switched to 3/8-inch drive.

While waiting for a part at Andrews Indian (a Triumph shop in greater Boston), 1 heard a hot-tempered young mechanic in the back, debating tool brands with a salesman.

“You tell me these other tools are guaranteed, but if one of ’em breaks, I have to drive clear across town to get that free replacement. And it won’t be any better than the one that broke. The way I see it, there’s only two brands of tools in this world-Snap-on and snap off”

I didn’t own any Snap-on tools-I couldn’t afford them. But I did recognize their beauty, the beauty of many tools. Service shops are visited at weekly intervals by tool trucks filled with beautiful, painfully expensive temptations. Young mechanics become addicts, owing their souls to the tool man, paying off their debts at so much a week, constantly tempted by the gleaming perfections up in the truck.

I bought the gleaming wrenches and the pliers with the joints so smooth and tight that you couldn’t feel any play in them.

But because many of the tools I already owned had come to me from particular people, or under special circumstances, my toolbox was becoming a kind of personal museum. I have several chisels that I bought used one summer that I spent with a young woman in Denver. I have a light ball-peen hammer that belonged to my great grandad, and a very second-handlooking Wizard plug socket that came from my maternal grandfather. Each time 1 use one of these tools, it has some of the aspects of a sacrament-not a big thing, but I’m always aware of it.

Lots of other tools relate to particular jobs, and the times in which I had to do them. I learned about gearboxes during the 1971 season, when we did 26 race weekends with the ingeniously unreliable Kawasaki Hl-R 500 Triple-a 75-horsepower engine with a 40-bhp gearbox. Therefore, my transmission pliers-like needle noses that open instead of close when you squeeze the handles-are an old favorite. They make it easy to handle eyeless snap rings, even the strongest ones. I have a pair of Robinson safety-wire twisters that twist to the left-specialordered so I could tell who had wired what. This expensive and now well-worn tool replaced a pile of falling-apart Air Force-surplus twisters that were barely better than twisting wire hand over hand. The bluing has worn off the handles and the spinner doesn’t fit very well anymore, but this tool is a pleasure to me.

There is a no-brand #3 Phillips screwdriver with a black-and-yellow plastic handle that always makes me think of building up engines on fresh cases at trackside, under the kind of hot sun that means a headache by dinner time. All the Snap-on combination wrenches (open on one end, box on the other) have short handles because I didn’t want fasteners over-torqued.

I have a big cardboard box full of second-line tools that I keep for special jobs. The cheaper the socket, the looser the fit, so when 1 need to turn something that’s an odd size, one of my cheez-o sockets often fits. When a tool has to be cut or welded to make a special, the raw material comes from this box.

In various places in my shop are special tools-some made to service fork dampers, one to hold Yamaha TZ750 cranks while their drive gear bolts are torqued. Another, 6 feet long, opens auto trunks when their locks fall out. One item-a 120-degree sector cut from a Yamaha transmission gear-I’ve had since 1966. Freddie Guttner, a German racer, seeing me struggling to tighten a clutch nut, kindly made this tool for me. Three gears in triangular mesh with each other cannot turn, so to jam the primary drive, you just engage this sector to both the crank and clutch gears, and they are locked solid, without damaging forces generated anywhere. Then, you can torque or un-torque clutch or crankshaft nuts easily. This is a fine tool, not available in stores.

Those with two-stroke experience know the frustration of trying to set or remove the springs that hold exhaust pipes to cylinder couplers. Pliers slip and knuckles suffer. Among my screwdrivers is a cheap-o with a diagonal slot cut in the side of its blade, to act as a hook for pipe springs.

End of problem.

I have two Bronze Age drill motors; one is 40 years old, a gift of that uncle, long ago, and rebuilt twice now. The other, my “new” drill, I bought in 1973. They still work. On the other hand, pop riveters are disloyal tools that fly apart without warning.

Need to check the shifting on a freshly assembled engine? I keep a 12mm shift pedal, from one of my Kawasakis of 197073, in the toolbox to keep myself from ever using a Vise-Grip plier to mash the shift shaft. There is a 12-inch straight-edge that has checked many a brake disc for flatness. Most measurements can be handled with either an inch/mm tape measure, or a 6inch vernier caliper, and these are veteran tools. Because I set these down and forget where I’ve put them, I have several of both, as with scribers and center-punches, giving me more chances to find one.

To set ignition timing, I have dial gauges left over from my long-ago association with the Kawasaki Al-R, the not-so-hot 250cc racer of 1967. The gauge, packed in a period wooden box with accessories, continues to serve. Degree wheel? Mine is off of some early ’60s defense gadget, and so small it annoyed the Vance & Hines crew into sending me one of their big ones.

There is, for me, real pleasure in pulling out a pair of 7mm combination wrenches for synching carb cables. These are doll’s house miniatures of larger tools, gracefully shaped and effective. A real anachronism are my spoke wrenches-a pair of early-days Japan dealer-kit items that I still use to build and true wire-spoked wheels.

Spin-tites are small sockets, used on a screwdriver-like handle. They reach in through bowl plugs to extract mainjets, and they fit all those odd-sized hex screws for which I’m too stingy to buy wrenches. I never wanted a giant roll-around with one of everything in it-too hard to transport. Rather, I keep only the sizes I need in the box, and leave the 9, 11, 15 and 16mm stuff unbought, back in the tool truck. They don’t fit anything I work on. Conversely, for the common sizes 7, 8, 10, 12, 13, 14 and 17mm, I have a pair of combination wrenches for each, one for the bolt, the other for the nut.

Grand Prix mechanics seem to like Thandles, and I can see the advantage of them-spinning fasteners in and out without having to change sockets. I think maybe I’ll get a set one day and try them.

Diagonal-cutting pliers-dikes-are a special concern. If their jaws don’t meet perfectly, and without dents caused by gripping things like hard dowel pins, the pliers won’t cut .020-inch safety wire cleanly. I don’t lend these to weenies, and I buy new when they don’t cut that wire. The retired pliers join the other second-line tools in that cardboard box.

As long as there’s life, there are tools.

The toolbox is a lot like the kitchen and its utensils. The work, and the tools used in performing it, are not just life’s routine. They’re a pleasure in their own right.