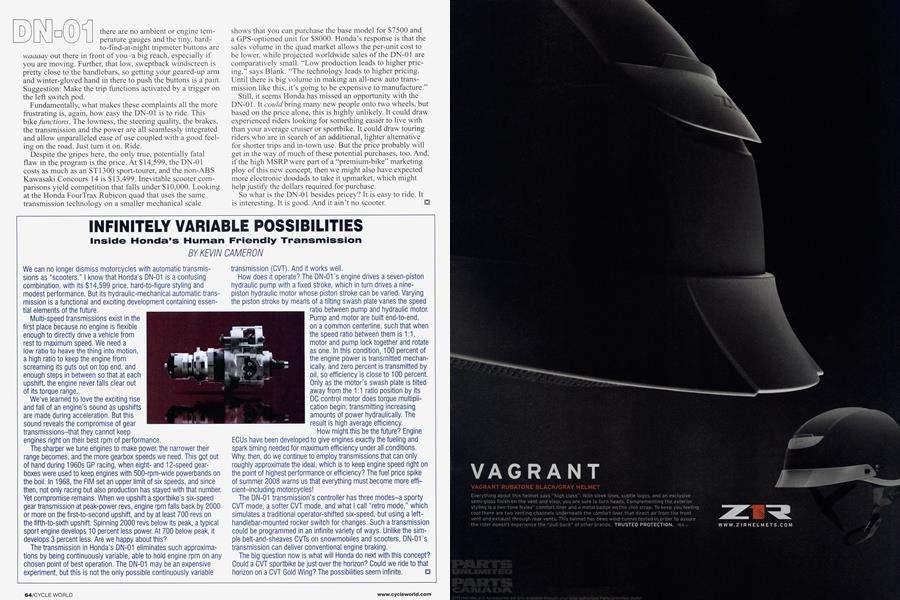

INFINITELY VARIABLE POSSIBILITIES

Inside Honda's Human Friendly Transmission

KEVIN CAMERON

We can no longer dismiss motorcycles with automatic transmissions as “scooters.” I know that Honda’s DN-01 is a confusing combination, with its $14,599 price, hard-to-figure styling and modest performance. But its hydraulic-mechanical automatic transmission is a functional and exciting development containing essential elements of the future.

Multi-speed transmissions exist in the first place because no engine is flexible enough to directly drive a vehicle from rest to maximum speed. We need a low ratio to heave the thing into motion, a high ratio to keep the engine from screaming its guts out on top end, and enough steps in between so that at each upshift, the engine never falls clear out of its torque range.

We’ve learned to love the exciting rise and fall of an engine’s sound as upshifts are made during acceleration. But this sound reveals the compromise of gear transmissions-that they cannot keep

engines right on their best rpm of performance.

The sharper we tune engines to make power, the narrower their range becomes, and the more gearbox speeds we need. This got out of hand during 1960s GP racing, when eightand 12-speed gearboxes were used to keep engines with 500-rpm-wide powerbands on the boil. In 1968, the FIM set an upper limit of six speeds, and since then, not only racing but also production has stayed with that number. Yet compromise remains. When we upshift a sportbike’s six-speed gear transmission at peak-power revs, engine rpm falls back by 2000 or more on the first-to-second upshift, and by at least 700 revs on the fifth-to-sixth upshift. Spinning 2000 revs below its peak, a typical sport engine develops 10 percent less power. At 700 below peak, it develops 3 percent less. Are we happy about this?

The transmission in Honda’s DN-01 eliminates such approximations by being continuously variable, able to hold engine rpm on any chosen point of best operation. The DN-01 may be an expensive experiment, but this is not the only possible continuously variable transmission (CVT). And it works well.

How does it operate? The DN-01 ’s engine drives a seven-piston hydraulic pump with a fixed stroke, which in turn drives a ninepiston hydraulic motor whose piston stroke can be varied. Varying the piston stroke by means of a tilting swash plate varies the speed

ratio between pump and hydraulic motor. Pump and motor are built end-to-end, on a common centerline, such that when the speed ratio between them is 1:1, motor and pump lock together and rotate as one. In this condition, 100 percent of the engine power is transmitted mechanically, and zero percent is transmitted by oil, so efficiency is close to 100 percent. Only as the motor’s swash plate is tilted away from the 1:1 ratio position by its DC control motor does torque multiplication begin, transmitting increasing amounts of power hydraulically. The result is high average efficiency.

How might this be the future? Engine

ECUs have been developed to give engines exactly the fueling and spark timing needed for maximum efficiency under all conditions.

Why, then, do we continue to employ transmissions that can only roughly approximate the ideal, which is to keep engine speed right on the point of highest performance or efficiency? The fuel price spike of summer 2008 warns us that everything must become more efficient-including motorcycles!

The DN-01 transmission’s controller has three modes-a sporty CVT mode, a softer CVT mode, and what I call “retro mode,” which simulates a traditional operator-shifted six-speed, but using a lefthandlebar-mounted rocker switch for changes. Such a transmission could be programmed in an infinite variety of ways. Unlike the simple belt-and-sheaves CVTs on snowmobiles and scooters, DN-01’s transmission can deliver conventional engine braking.

The big question now is what will Honda do next with this concept? Could a CVT sportbike be just over the horizon? Could we ride to that horizon on a CVT Gold Wing? The possibilities seem infinite. n