THE SCHISM

RACE WATCH

Roadracing at War

KEVIN CAMERON

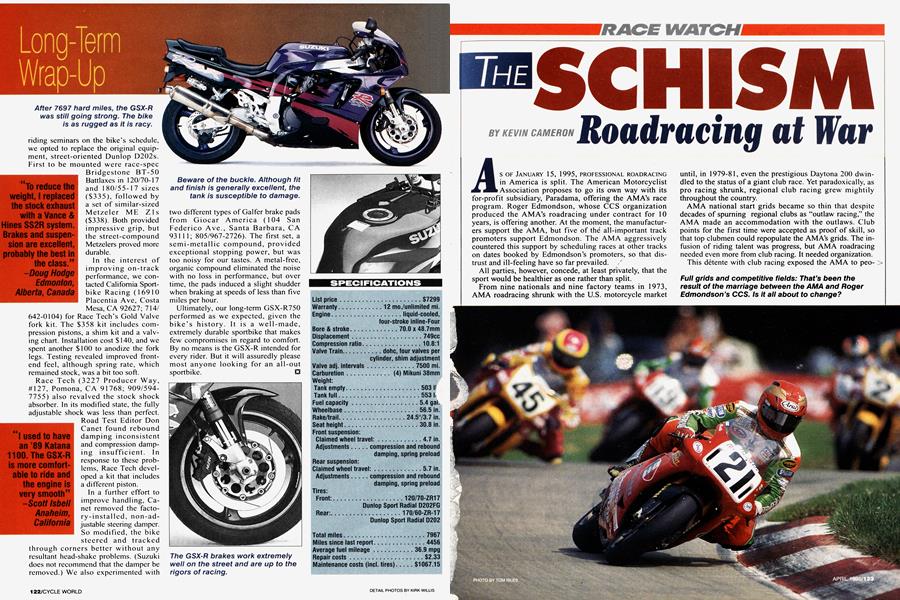

AS OF JANUARY 15, 1995, PROFESSIONAL ROADRACING in America is split. The American Motorcyclist Association proposes to go its own way with its proposes go way for-profit subsidiary, Paradama, offering the AMA’s race program. Roger Edmondson, whose CCS organization produced the AMA’s roadracing under contract for 10 years, is offering another. At the moment, the manufacturers support the AMA, but five of thé all-important track promoters support Edmondson. The AMA aggressively countered this support by scheduling races at other tracks on dates booked by Edmondson’s promoters, so that distrust and ill-feeling have so far prevailed.

All parties, however, concede, at least privately, that the sport would be healthier as one rather than split.

From nine nationals and nine factory teams in 1973, AMA roadracing shrunk with the U.S. motorcycle market

until, in 1979-81, even the prestigious Daytona 200 dwindled to the status of a giant club race. Yet paradoxically, as pro racing shrunk, regional club racing grew mightily throughout the country.

AMA national start grids became so thin that despite decades of spurning regional clubs as “outlaw racing,” the AMA made an accommodation with the outlaws. Club points for the first time were accepted as proof of skill, so that top clubmen could repopulate the AMA’s grids. The infusion of riding talent was progress, but AMA roadracing needed even more from club racing. It needed organization.

This détente with club racing exposed the AMA to peopie who ran races every weekend, not just three or four times a year, as in the sparest of AMA calendars. During this period the AMA encountered Roger Edmondson. Edmondson, once a part-time racer and hi-fi dealer, had involved himself in the Western-Eastern Racing Association (WERA), a national association of regional racing clubs. Later, breaking away from WERA, he formed his own organization, the Championship Cup Series (CCS). Edmondson approached the production of roadracing systematically, and learned quickly from experience. CCS became a going concern, but to reach national scale, it needed an umbrella. The AMA became that umbrella, and in return for AMA support, Edmondson delivered a complete, ready-made non-pro, or farm-

league, scries from which the professional racing classes could draw future stars. AMA nationals now included the top CCS classes, which replaced the old AMA hierarchy of Novice, Junior and Expert licensing.

There resulted an outwardly seamless marriage of two quite different organizations and outlooks. The AMA is non-profit, dedicated to furthering the interests of its motorcycling members, much as the AAA does for fourwheeled motorists. It also included a professional racing program of many years’ standing. The CCS was a purcbusiness, definitely for-profit operation, its income derived from license and entry fees, its product being efficiently run roadraces. and organization to racing that had lacked those qualities. He made the program work.”

The AMA, having many other responsibilities, gladly left roadracing to CCS, and with immediate benefit.

All parties concede that the sport would be heal! he r as one, rather than split.

Under the “old AMA,” the typical volunteer official had too often been an older man with a belly, a whistle and an attitude, who enjoyed his scrap of weekend power over younger people. Many a rider remembers being told to “Get a haircut, kid, or don’t come back." Riders were suspended for riding non-AMA “outlaw events," and this forced people to ride those events under comical assumed names like Sumner Tunnel or Dick Tator. Advisory committees and professional competition managers could recommend courses of action, but any action was subject to reversal by AMA’s Board of Trustees. Rightly or not, the old board was seen by many as the past trying to prevent the future. It was often proposed that the AMA create a separate, for-profit racing organization to build up motorcycle sports. That was not acceptable to the board, which felt an understandable responsibility to control any enterprise bearing the AMA name.

The partnership with CCS was therefore a workable compromise. Bringing in CCS under contract brought efficient race management, but kept the aura of AMA control. In the field, CCS replaced the old-timers with experienced club-racing veterans.

Procedures were streamlined, the rule book was updated and clarified. Race operations became uniform from coast to coast. Edmondson’s taste for display (his big motorhomes, for example) drew some criticism, but all agreed, as AMA Board Chairman Paul Dean said recently, that “Roger brought order

The dual nature of this arrangement contained seeds of trouble to come.

Any related responsibility not quickly dealt with by AMA was taken up and handled by Edmondson and CCS. The AMA gradually abdicated its control over roadracing to its efficient partner.

A joint venture existed in a de facto sense, but the value brought to it by each partner was undefined.

There was also long-term, strategic change from within the AMA. President Ed Youngblood knew his organization needed a businesslike, forprofit subsidiary to develop its racing. He also knew that the board of trustees, as it then was, was an obstacle. Youngblood worked patiently for change. Over time, new faces appeared on the board. Decision-making was eased and speeded by new voting rules. In 1990, a new Professional Racing Strategic Planning Committee began to consult experts throughout motor sport, seeking a course for AMA. Edmondson was discussed as the natural choice to be president of a future AMA racing corporation.

At the end of the 1993 season, both Youngblood and Edmondson sought a meeting. Edmondson wanted to discuss new administrative means of squaring field operations with homeoffice staff. Youngblood had a more ambitious agenda. Its main points were, as Edmondson remembers them:

( 1 ) We’d like CCS to continue as an AMA activity; (2) we’ll hire you as manager, on a salary; and (3) we’ll buy-out your half of our joint venture.

Edmondson offered to sell, naming

This detente with club racing exposed the AiPIA to people who ran club races every weekend....

a figure. He also offered to lease the series from the AMA for 10 years at the same figure. He recalls, “Ed was stunned that I didn’t want to be on salary.”

As Dean says, “Ed, at first, favored giving Roger a sweet deal,” while noting that Edmondson’s proposal, “ignored the value also brought to racing by the AMA.” Members of the board of trustees, however, were surprised that Youngblood did not just reject this proposal out of hand. Their view was that Edmondson had done a job for the AMA, and had been paid for it. But Edmondson believed there was value in the new classes, and value in the order CCS had brought to AMA nationals.

The AMA was at last ready to restructure roadracing, but each of two parties had a piece of it. The AMA had the name, the tradition and the clout. Edmondson had CCS, which actually produced the races. Could these pieces be united agreeably, or was a split inevitable?

There was now an escalation in stages, from simple difference of opinion, to conflict of outlook and language, to outright mutual distrust. Each side managed, apparently without intending it, to offend the other, leading to counter-offense. The AMA board is a third party-slow-moving, at a distance from the action, but obliged to act according to its real responsibility to the AMA’s members, not all of whom care at all about roadracing. The intense personalities of the principals greatly complicated the monthslong, unsuccessful negotiation.

Youngblood is busy with many undertakings, including the AMA museum, inevitable lawsuits, membership, legislation and racing of all kinds. Edmondson is focused tightly on roadracing alone. Youngblood has the reputation of tolerating only small deviations from what he expects of people. The decades-long series of so-called miracle managers, hired to build pro racing, then fired in implied disgrace a few months later, testifies to this. Edmondson, because he is quick and well-spoken, and can run meetings in a businesslike way, gives a clear impression of tough leadership. But he is in fact quite thin-skinned and easily offended. Both men are, within their respective spheres, genuine crusaders and visionaries. Either one, had he worked equally hard in, say, real estate or plumbing supplies, would now be wealthy.

Edmondson sums up the difference in outlook by pointing to Daytona, 1994. The AMA chose, only days before Daytona registration opened, to break off negotiation and try to oper-

The CCS was a pure business, for-profit operation.

ate the event on its own, using hastily trained motocross personnel. To Edmondson, this willingness to use Daytona as on-the-job-training showed that AMA had no understanding of, or respect for, racing as a business.

Dean sees the controversy differently. He says, “In Roger, we were dealing with a man who couldn't take yes for an answer.’’ Characterizing the board as conscientious and fair, he adds that Edmondson “always wanted something else,’’ that he alienated Youngblood and the board by what Dean calls “the irrationality of his negotiating methods.”

The France family, which owns Daytona International Speedway, wasn’t willing to accept the risk of a botched show, especially considering that the ’94 event would be televised live for the first time. The Frances stepped in at the last minute and strongly suggested (as only they can, using easily understood words of one syllable or less) that the AMA run the

The I~jpiealA~7L4 volunteer too often had a belly, a whistle and an attitude,

event with Edmondson’s organization.

With Daytona over, the cycle of distrust rolled again. A new agreement was worked out at a Chicago meeting. As Dean tells it, “We kept grinding the rough edges off until we thought we had a gem. We felt pretty good about it.” The story of what happened next is unrecognizably different as told by the two sides; there was lawyer talk, impatience, a deadline set. Edmondson says he began the handover to the AMA of the machinery of administration-records, computer discs, mailings-in expectation that agreement was a certainty. The AMA sees instead intransigence, a missed deadline, finally a need to move forward without Edmondson.

After the ’94 season ended, the race promoters held a meeting with the AMA. Edmondson waited in the wings. He says he assumed all he could hope for was a secondary position to the AMA, attempting to sell supporting and lesser two-day events to promoters whose primary business would be AMA nationals. By noon, the promoters and the AMA were deadlocked, and Edmondson was called in. Several of the promoters liked what he had to say. As Edmondson puts it, “Our plan fit their requirements, so it was chosen.” Edmondson’s organization had been thrust into the number-one position. The AMA might not value Edmondson’s product, but it appeared that many of the promoters did.

When asked his opinion of why promoters might act this way, Jim France replied, “Continuity.”

Since then, the AMA has gone ahead building up an independent organization to operate its national roadraces, under the management of Paradama, a new, for-profit subsidiary which is wholly AMA-owned and financed. Edmondson has likewise carried on with plans to produce races on their traditional dates. Although the promoters see the dates as theirs to assign as their business interests require, the AMA sees Edmondson as “stealing our dates.” All parties to the dispute agree that an agreement would be better for the sport than a split series. The intensity of the dispute has now, however, deformed the issues so they will no longer fit together as they once did.

Dean and others feel that the overhanging potential of big future income from roadracing is driving the dispute, and that the creation of Paradama was the trigger. Edmondson says he is misjudged as being financially motivated simply because the language of business is profit and loss, and he speaks that language. He says the real issue is trust, and feels for his own reasons that he can no longer trust the AMA. Dean, meanwhile, says the promoters may be driven less by business concerns than by a fear, generated by Paradama’s exis-

Both Fdmondson and Youngblood are crusaders and visionaries....

tence, that the AMA means to take over not only race operations but promotion, as well.

Often discussed is the possible influence, intended or not, of the France family. Some observers, knowing that the Frances have renewed Edmondson’s dates as well as that of the AMA’s traditional Daytona 200, interpret this not as impartiality but as somehow favoring Edmondson. Might promoters, they suggest, favor Edmondson, thinking this might be pleasing to the Frances?

Edmondson views this as a red herring generated to counter what he says is obvious, which is that the promoters who have given him dates have done so for sound business reasons alone. “If the AMA are such good listeners,” he asks, “why were they surprised when these promoters chose our program? Are they genuinely trying to do what is best for motorcycling, or just best for AMA motorcycling?”

Although the manufacturers say they will back the AMA’s series, they have called upon both parties to settle their differences, believing a split will be harmful to a young sport on the threshold of real national popularity. Honda recently offered its corporate campus as a neutral ground for discussion, and Yamaha has offered mediation.

Also encouraging is the presence at the head of the Paradama board of the w'ell-respected motorsports lawyer and race promoter, Cary Agajanian. For his part, Edmondson has retained David Atlas, a former attorney for racing mega-businessman Roger

In Edmondson, we were dealing with a man who couldn't take yes for an answer.

Penske. Before New Year's Day, Ed mondson said, "Agajanian is a pro. I think the two of them can talk. I am counting on business sense and com mon sense to fix this."

Moving the discussion to profes sional intermediaries offers promise, for it distances the heat of personality and mutual offense from the problem. Agajanian, a promoter himself, knows that it can sometimes be diffi cult to negotiate with the AMA. With or without Edmondson, he promises improved management and improved relations with promoters.

“If AMA does a good enough job, they (the promoters) will want to do business with us,” he has said. He be-

The AJIA has said it welcomes the competition.

Heves strongly that sanctioning bodies should be free of special interest, instead of being dominated by promoters, manufacturers, sponsors or team owners.

As the meetings and negotiations continue, the question remains: Where is the value, and whose is it? After that initial, pivotal meeting between Youngblood and Edmondson at which a buy-out was first discussed, the AMA board asked this simple question: What are we buying? Its view is that Edmondson has already been paid for his management services, all that was his to sell. The four classes developed by CCS-750 and 600cc Supersport, Endurance, and U.S. TwinSports-exist, in the board's view, in the public domain, and are not different from similar classes elsewhere in the world. Edmondson’s reply is equally clear: If the AMA isn’t interested, the forces of free enterprise invite him to measure the value of his product in the marketplace. And the AMA has said, “We welcome the competition.” Roadracing fans can only hope the parties recognize each others’ humanity, set aside past offense, and find agreement. Quickly. Before this economic cold war turns hot. □

Kevin Cameron is an earned life member of the AMA and in the capacity of an AMA tech inspector, has worked with both the AMA and Edmondson. It should also be noted that in addition to Paul Dean's AMA responsibilities, he is Cycle World 's editorial director. Dean had no part in the preparation of this story, other than to be interviewed for it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

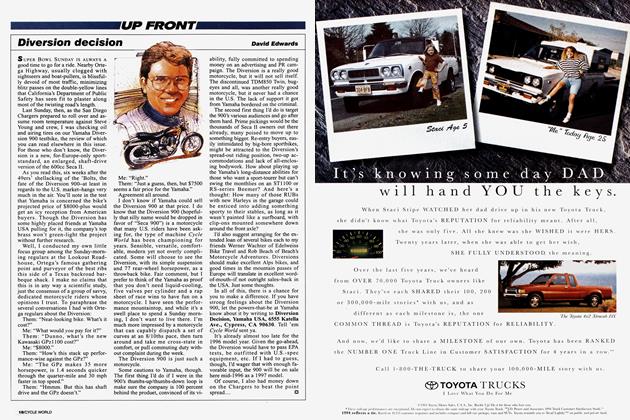

Up FrontDiversion Decision

April 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThinking Small

April 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTool Morality

April 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Rumors Are True! Yamaha's Twin Is In.

April 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia's Moto' 6.5 Comes Alive

April 1995 By Robert Hough