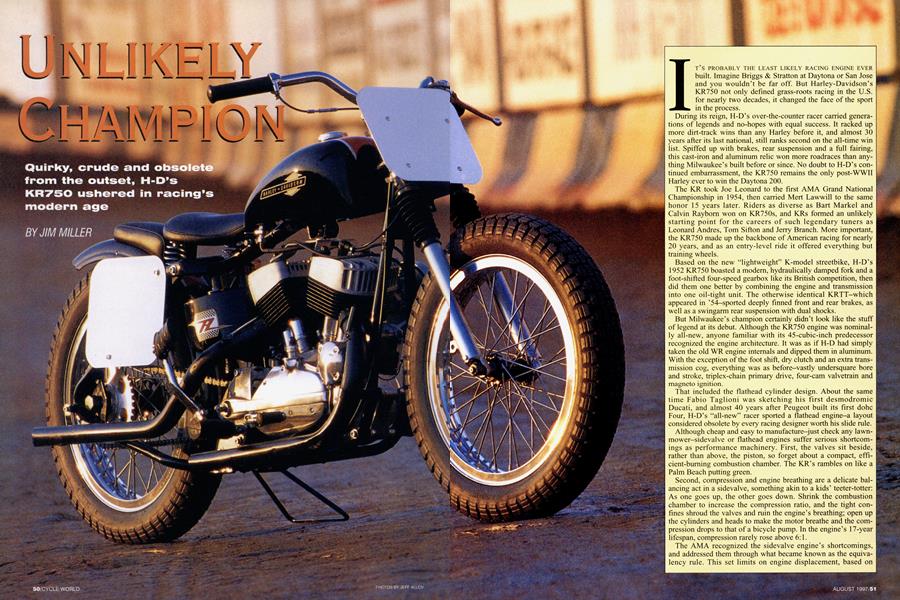

UNLIKELY CHAMPION

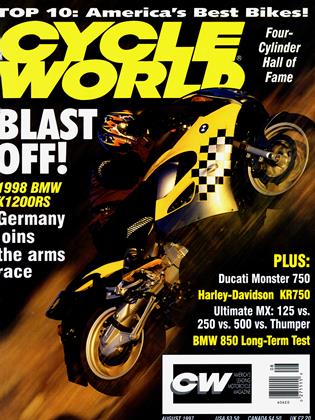

Quirky, crude and obsolete from the outset, H-D’s KR750 ushered in racing’s modern age

JIM MILLER

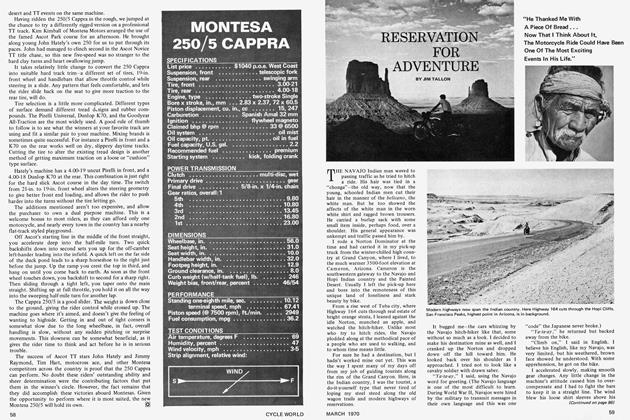

IT'S PROBABLY THE LEAST LIKELY RACING ENGINE EVER built. Imagine Briggs & Stratton at Daytona or San Jose and you wouldn't be far off. But Harley-Davidson's KR750 not only defined grass-roots racing in the U.S. for nearly two decades, it changed the face of the sport in the process. During its reign, H-D's over-the-counter racer carried generations of legends and no-hopes with equal success. It racked up more dirt-track wins than any Harley before it, and almost 30 years after its last national, still ranks second on the all-time win list. Spiffed up with brakes, rear suspension and a full fairing, this cast-iron and aluminum relic won more roadraces than anything Milwaukee's built before or since. No doubt to H-D's continued embarrassment, the KR750 remains the only post-WWII Harley ever to win the Daytona 200.

The KR took Joe Leonard to the first AMA Grand National Championship in 1954, then carried Mert Lawwill to the same honor 15 years later. Riders as diverse as Bart Markel and Calvin Rayborn won on KR75Os, and KRs formed an unlikely starting point for the careers of such legendary tuners as Leonard Andres, Tom Sifton and Jerry Branch. More important, the KR750 made up the backbone of American racing for nearly 20 years, and as an entry-level ride it offered everything but training wheels.

Based on the new 1ightweight" K-model streetbike, H-U's 1952 KR750 boasted a modern, hydraulically damped fork and a foot-shifted four-speed gearbox like its British competition, then did them one better by combining the engine and transmission into one oil-tight unit. The otherwise identical KRTT-which appeared in `54-sported deeply finned front and rear brakes, as well as a swin~arm rear suspension with dual shocks.

But Milwaukee's champion certainly didn't look like the stuff of legend at its debut. Although the KR750 engine was nominal ly all-new, anyone familiar with its 45-cubic-inch predecessor recognized the engine architecture. It was as if H-D had simply taken the old WR engine internals and dipped them in aluminum. With the exception of the foot shift, dry clutch and an extra trans mission cog, everything was as before-vastly undersquare bore and stroke, triplex-chain primary drive, four-cam valvetrain and magneto ignition.

That included the flathead cylinder design. About the same time Fabio Taglioni was sketching his first desmodromic Ducati, and almost 40 years after Peugeot built its first dohc Four, H-D's "all-new" racer sported a flathead engine-a layout considered obsolete by every racing designer worth his slide rule.

Although cheap and easy to manutäcture-just check any lawn mower-sidevalve or flathead engines suffer serious shortcom ings as performance machinery. First, the valves sit beside, rather than above, the piston, so forget about a compact, effi cient-burning combustion chamber. The KR's rambles on like a Palm Beach putting green.

Second, compression and engine breathing are a delicate bal ancing act in a sidevalve, something akin to a kids' teeter-totter: As one goes up, the other goes down. Shrink the combustion chamber to increase the compression ratio, and the tight con fines shroud the valves and ruin the engine's breathing; open up the cylinders and heads to make the motor breathe and the com pression drops to that of a bicycle pump. In the engine's 17-year lifespan, compression rarely rose above 6:1.

The AMA recognized the sidevalve engine's shortcomings, and addressed them through what became known as the equiva lencv rule. This set limits on engine displacement, based on head design. Overhead-valve or overhead-cam engines were allowed a 500cc maximum; fatheads were granted an additional 250cc.

The equivalency rule began as little more than a fmger-inthe-wind approximation, but it worked far better-and for far longer-than anyone expected. Despite its 50 percent displacement advantage, the KR rarely enjoyed any substantial horsepower advantage over the Triumph Twins or BSA and Matchless Singles.

“If the English had put the same kind of development into their engines that we put in, they would have tom us a new ass,” says Dick O’Brien, H-D’s racing director from 1957 to 1983. “Most of them figured we had around 70 horsepower, but the best we ever got was around 57.”

Balancing the simplicity of the KR’s fathead top end, its crankcase housed enough gears and bearings to keep an armored division on the move. The convoluted valvetrain it inherited from the WR-and passed on virtually intact to the XR and Sportster-consisted of a gearcase filled with four stubby camshafts, with a set of roller tappets acting directly on the valve stems.

The timing marks on the KR’s cams were usually close enough for the garage mechanics who populated the lower echelons of Class C tuners; serious guys cut the cams off their shafts and rewelded them to exact spec. In addition, the cam drive also spun the front-mounted magneto, which provided plenty of gear lash to throw off both valve and ignition timing.

The KR’s dry-sump lubrication system depended on a timed breather to keep the crankcase free of excess oil, which added one more pitfall for amateur tuners. Timed incorrectly, the breather would allow oil to build up in the cases, wrapping itself around the crankshaft like caramel around an apple. The KR’s already meager horsepower production would plummet. “Tom Sifton always said that the guy who designed the oiling system on the KR was either the smartest son of a bitch in the world or the dumbest, he didn’t know which,” recalls O’Brien.

The KR’s lawnmower-like simplicity was both a blessing and a curse. “They didn’t require a lot of maintenance,” says racer Mert Lawwill. “You’d do two major rebuilds a year, and a top end every six or eight races.” Despite the engine’s myriad ball, needle and roller bearings, a rebuild wouldn’t tax the average mechanic’s abilities.

But the engine’s antiquated combustion chambers, convoluted valve gear and internal quirks meant the KR responded best to patience and a careful hand. Wholesale changes typically reaped wholesale disaster, so extracting horsepower from the KR was a matter of subtleties. The best tuners doted over the smallest details, and cutting friction became an almost religious crusade. “When you’ve got that little power, you look at everything,” says Jerry Branch, of Branch Flowmetrics, who began tuning KRs as a Harley service manager in Long Beach, California.

Branch even went to the point of building a fixture to spin a fully completed KR engine with an electric motor, pumping a mix of oil and valve-lapping compound through the engine for hours to bed-in the V-Twin’s numerous gear faces. He’d then pull it apart, clean it and install fresh bearings. “When it was done, you could just about turn the countershaft sprocket with your breath,” he recalls.

Ironically, it was the KR’s antiquated design that forced tuners to find modem solutions-and change the face of racing. When Gary Nixon and a revitalized Triumph soundly trounced H-D during the 1967 season, taking both Daytona and the Number One plate, the double loss called for extreme measures. O’Brien enlisted aid from an unlikely pair of sources: BSA tuning wizard C.R. Axtell and the California Institute of Technology.

During the off-season, Lawwill had persuaded O’Brien to pack a KR engine off to Axtell, who owned one of motorcycling’s first flow benches. O’Brien spent the winter shuttling between Milwaukee and L.A., working a week at a time in Axtell’s shop, checking and changing airflow patterns in the KR’s cast-iron cylinders.

What came out was a set of domed pistons with matching heads, but the domes weren’t designed to boost compression. Instead, they directed the airflow over the tops of the pistons, drawing the mixture directly into the cylinder bores. Combined with the new megaphone exhaust and dual Tillotsen carburetors, the flow work improved cylinder filling immensely.

O’Brien split his time in California between Axtell’s flow bench and Cal Tech’s 10-foot wind tunnel, working with fiberglass pioneer Dean Wixom on a full-scale model of a faired KR roadracer. Everything from the seat/tailsection to the windshield cutaways was subtley reshaped. “The year before we went to Cal Tech, Fred Nix qualified around Daytona at about 140. During the winter we’d picked up about 5 horsepower through the engine work. When I told that to Bill (Bettes, Cal Tech’s wind-tunnel engineer), he said, ‘You’ll run 150.’”

Harley-Davidson showed up with seven official team riders at the 1968 Daytona 200, with each bike painted in the new orange-and-black factory colors. Roger Reiman took the pole at 149.80 mph, and all seven qualified in the top 10. With a winning average of 101.3 mph, Cal Rayborn became the first rider to top 100 mph for the 200-miler, adding nearly 5 mph to the race record.

Jerry Branch left Daytona a changed man. “Before (Axtell’s work), everybody was doing flow by eyeball,” says Branch. “When I flew out the Monday after Daytona, I decided on the airplane to build a flow bench. Once I got back to L.A., I built two-one for me and one for Harley-Davidson.” Branch Flowmetrics was in business, and from then on a flow bench became a fixture in any serious racing shop.

While a remarkable winner on pavement, the KR is best remembered in brakeless, hardtail form, booming through the comers of a blue-groove mile in the bare hands of a Bart Markel or a George Roeder, skewed wildly sideways with a fine roostertail of dirt fanning off its rear tire. Of the nearly 150 national wins scored on KR750s, more than 100 of them came on dirt, adding to a tally that included thousands of Saturday-night feature races across America.

Lawwill, for one, preferred the KR as a dirt-tracker. “I loved them. Being a flathead, they didn’t have a lot of weight up high, and the low center of gravity meant they were easy to pitch from side to side,” says the 1969 Grand National Champion. Despite most H-D riders’ early preference for the KR’s hardtail frame, Lawwill grafted a swingarm onto his Harley dirt-tracker after switching from a BSA Gold Star in 1964. “I figured if suspension’s good for one wheel, it should be good for the other,” he says. By the end of the decade, only die-hards raced sans shocks, even on the smooth mile and half-mile tracks.

With the elimination of the AMA’s equivalency rule in 1969, everyone predicted the end of the KR’s dominance. Expectations ran high at Nazareth, Pennsylvania, the first race allowing ohv 750s. BSA and Triumph rolled out their new Triples in dirt-track trim, fully expecting to stomp the flathead V-Twin into the history books on the fast, H/s-mile track. By day’s end, Fred Nix set fastest time, placed first in his heat race and won the main by half a lap-on a KR. Despite the competition’s growing strength through the year, Lawwill took the championship for 1969, fittingly winning the last race of the season at Ascot. It was the KR’s final national win.

The following year, Lawwill was forced to shift to the KR’s star-crossed successor, the iron XR-750. More powerful but brutally unreliable, the KR’s ohv replacement likely cost him the championship in 1970. Faced with the XR’s fragility, Lawwill went back to his underpowered KR. With the 1970 season over, he bolted a pair of Mikuni carburetors onto the KR as an experiment. It picked up about 3 horses. “If I’d done that at the beginning of the season, I probably would have repeated as Number One,” he muses.

After lording over much of the KR’s history, Dick O’Brien refuses to wax poetic about the bike’s success. “It was a lot of people doing a lot of goddamned hard work,” he contends. But that work set standards that remain even today.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Other Ten Best

August 1997 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Thousand Phone Calls

August 1997 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCPhilosophic Conversions

August 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1997 -

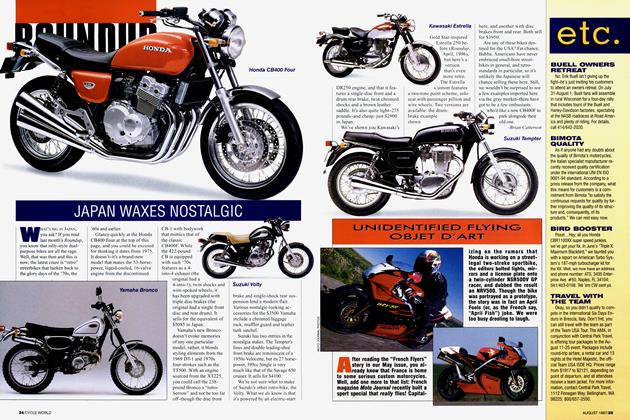

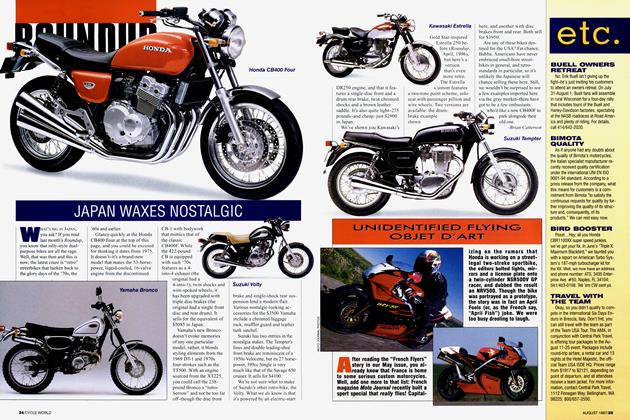

Roundup

RoundupJapan Waxes Nostalgic

August 1997 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupUnidentified Flying Objet D'Art

August 1997