THE ECONOMICS OF RESTORATION

Concours cashflow

I WAS STANDING IN THE SHOP AT STAR CYCLE IN TUCSON, Arizona, listening to Mick Frew, proprietor and friend, explain Frew’s First Law Of Restoration. “There are three ways to do this: good, fast and cheap. You can have any two of those three,” explained Mick. “You can have it good and fast, but it won’t be cheap; or good and cheap, but it won’t be fast; or fast and cheap, but it won’t be good. Take your pick.”

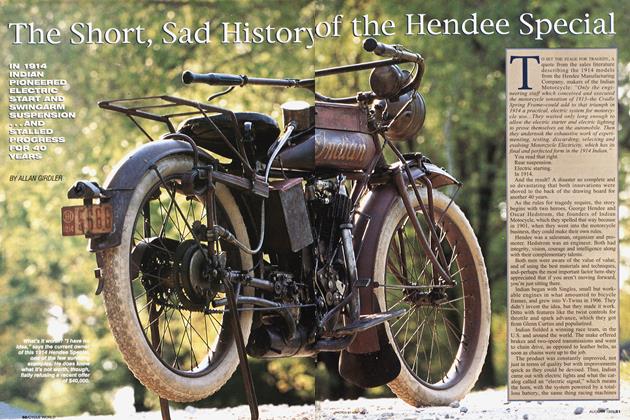

After toting my 1954 Harley-Davidson KR750 around in boxes for more than 20 years, I decided good and cheap made eminent-if not imminent-sense. Besides, it had a nice ring to it. But as even Donald Trump can tell you, cheap is a relative term. Even with Frew’s good-guy creative accounting, the final tally, almost four years later, came to nearly half the current value of the bike. But if Fd bought the unrestored dirt-tracker at today’s market value-instead of the $550 I paid for it in 1972-and taken the “good and fast” option, I’d be anywhere from $6000 to $8000 upside-down in it.

Nose-bleed prices aside, the fact is a good professional restoration requires a huge outlay of time, much of which the average owner never pays for. “The other day, I was working on my own Gold Star, mounting the shocks and swingarm. After I’d found the correct washers and nuts, cleaned them, chased the threads and then bolted it together, I’d spent almost an hour and half,” says Frew. “How can you charge someone $75 just to mount the swingarm on a bare frame?”

Denny Berg, who has restored bikes for everyone from Cycle World's own Editor David Edwards to Jay Leno, has been on the losing end of several restorations. Berg’s work has won numerous trophies, including four class wins at the 1996 Del Mar Concours. “The thing about restorations is that (as a builder) your hands are tied. You need a certain part, or a certain paint color, and if you deviate, everybody’s going to know it,” he says.

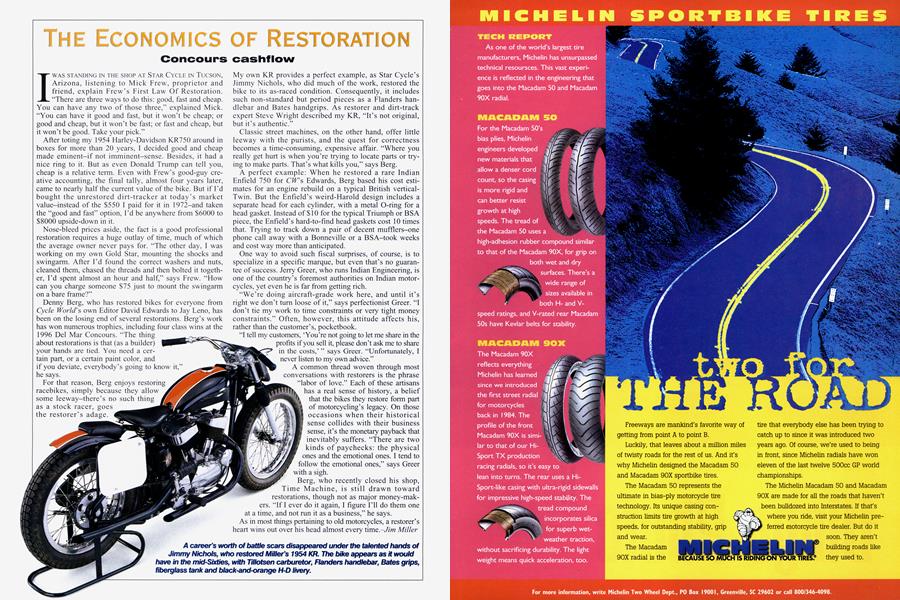

For that reason, Berg enjoys restoring racebikes, simply because they allow some leeway-there’s no such thing as a stock racer, goes the restorer’s adage. My own KR provides a perfect example, as Star Cycle’s Jimmy Nichols, who did much of the work, restored the bike to its as-raced condition. Consequently, it includes such non-standard but period pieces as a Flanders handlebar and Bates handgrips. As restorer and dirt-track expert Steve Wright described my KR, “It’s not original, but it’s authentic.”

Classic street machines, on the other hand, offer little leeway with the purists, and the quest for correctness becomes a time-consuming, expensive affair. “Where you really get hurt is when you’re trying to locate parts or trying to make parts. That’s what kills you,” says Berg.

A perfect example: When he restored a rare Indian Enfield 750 for CÍWs Edwards, Berg based his cost estimates for an engine rebuild on a typical British verticalTwin. But the Enfield’s weird-Harold design includes a separate head for each cylinder, with a metal O-ring for a head gasket. Instead of $10 for the typical Triumph or BSA piece, the Enfield’s hard-to-fmd head gaskets cost 10 times that. Trying to track down a pair of decent mufflers-one phone call away with a Bonneville or a BSA-took weeks and cost way more than anticipated.

One way to avoid such fiscal surprises, of course, is to specialize in a specific marque, but even that’s no guarantee of success. Jerry Greer, who runs Indian Engineering, is one of the country’s foremost authorities on Indian motorcycles, yet even he is far from getting rich.

“We’re doing aircraft-grade work here, and until it’s right we don’t turn loose of it,” says perfectionist Greer. “I don’t tie my work to time constraints or very tight money constraints.” Often, however, this attitude affects his, rather than the customer’s, pocketbook.

“I tell my customers, ‘You’re not going to let me share in the profits if you sell it, please don’t ask me to share in the costs,’ ” says Greer. “Unfortunately, I never listen to my own advice.”

A common thread woven through most conversations with restorers is the phrase “labor of love.” Each of these artisans has a real sense of history, a belief that the bikes they restore form part of motorcycling’s legacy. On those occasions when their historical sense collides with their business sense, it’s the monetary payback that inevitably suffers. “There are two kinds of paychecks: the physical ones and the emotional ones. I tend to follow the emotional ones,” says Greer with a sigh.

Berg, who recently closed his shop, Time Machine, is still drawn toward restorations, though not as major money-makers. “If I ever do it again, I figure I’ll do them one at a time, and not run it as a business,” he says. As in most things pertaining to old motorcycles, a restorer’s heart wins out over his head almost every time.

Jim Miller

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

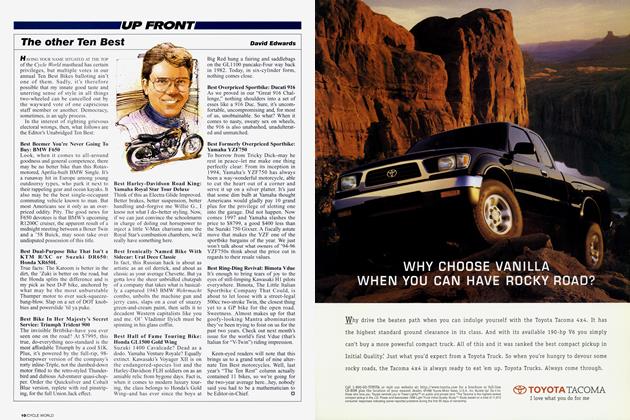

Up FrontThe Other Ten Best

August 1997 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Thousand Phone Calls

August 1997 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCPhilosophic Conversions

August 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1997 -

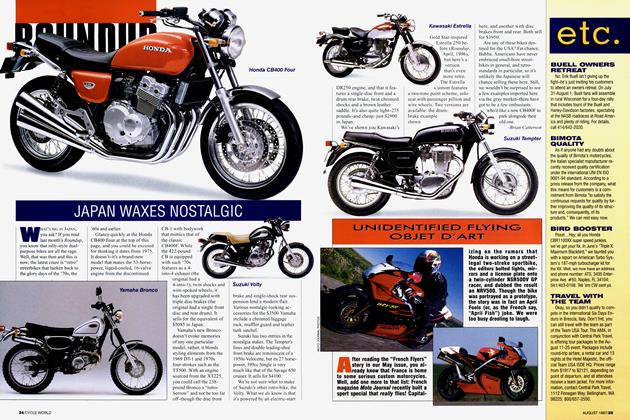

Roundup

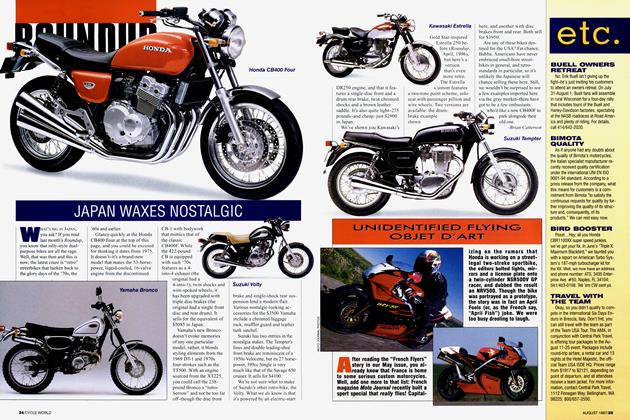

RoundupJapan Waxes Nostalgic

August 1997 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupUnidentified Flying Objet D'Art

August 1997