Clipboard

RACE WATCH

Factory warfare: Ducati vs. Honda in WSB

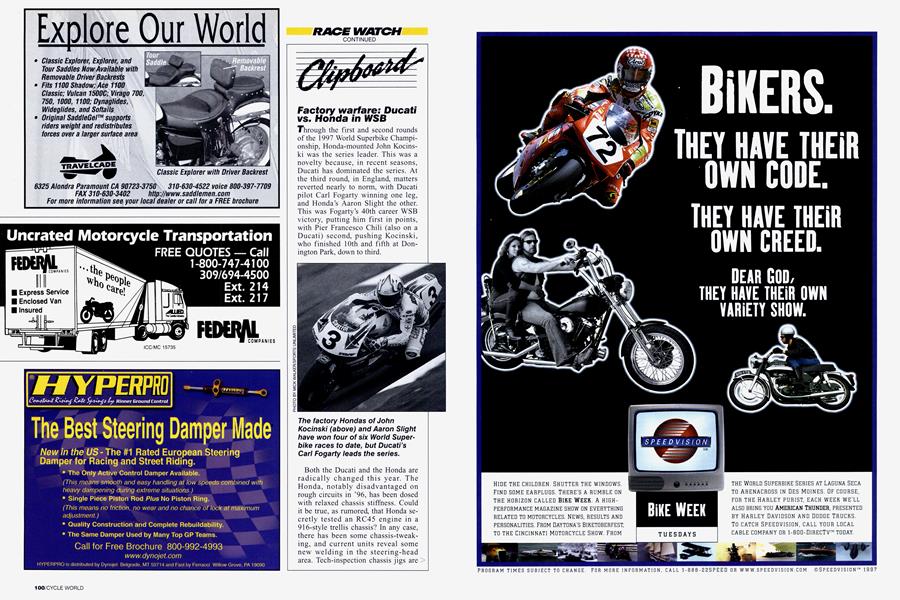

Through the first and second rounds of the 1997 World Superbike Championship, Honda-mounted John Kocinski was the series leader. This was a novelty because, in recent seasons, Ducati has dominated the series. At the third round, in England, matters reverted nearly to norm, with Ducati pilot Carl Fogarty winning one leg, and Honda’s Aaron Slight the other. This was Fogarty’s 40th career WSB victory, putting him first in points, with Pier Francesco Chili (also on a Ducati) second, pushing Kocinski, who finished 10th and fifth at Donington Park, down to third.

Both the Ducati and the Honda are radically changed this year. The Honda, notably disadvantaged on rough circuits in ’96, has been dosed with relaxed chassis stiffness. Could it be true, as rumored, that Honda secretly tested an RC45 engine in a 916-style trellis chassis? In any case, there has been some chassis-tweaking, and current units reveal some new welding in the steering-head area. Tech-inspection chassis jigs are supposed to guarantee that engine, steering head and swingarm pivot are in the homologated positions. But who decides what those positions are? When does factory tolerance become intentional redesign?

RC45 engine performance has benefited from a switch to two injectors per stack-one close to the valve for lowerrpm performance, the other hanging above the open end of the trumpet in F-l style, to give longer fuel-evaporation time at higher rpm. There may also be benefits in smoother bottomend acceleration. Con-rod lubrication has been upgraded by feeding oil into the ends of the crank, and not through the main bearings.

Wild speculation attends a large electronics box, connected to both the ignition computer and rear-wheel sensor. Is this the long-awaited traction control, a device that might smooth corner exits by limiting or otherwise controlling wheelspin? Or does it serve the Linked Braking System, so boldly proclaimed by fairing logos? Do professional riders need the same help that novice road riders do in synchronizing front and rear brake action? Or does this system operate in another way?

One suggestion is that the device may maximize chassis squat during braking; applying the rear brake slightly ahead of the front allows time for the rear caliper to “wind up” the swingarm, lowering the rear of the bike and permitting a slightly higher level of braking force. Antispin theorists point to the rear-wheelspeed sensor, but this is a normal part of the data-acquisition system. Anti-spin could just as well operate from tachometer data, and be completely invisible. To satisfy the AMA’s official misgivings, Honda’s U.S. Superbike squad has sometimes run races with the rear-wheel speed sensor disconnected. Would traction control be useful during corner exits without the yaw-detection sensors used in auto systems? No facts exist, and U2 overflights won’t help us. We need a man inside. -Kevin Cameron

Honda MX: Big troubles at Big Red

The 1997 AMA Supercross season marked the first time in 16 years that a Honda factory rider failed to win a 250cc main event. It was also the first time in a decade that a Honda rider didn’t claim the series championship. All of which leads one to ask: What happened to Team Honda?

Supercross has changed dramatically during the past 15 years. The growth of “extreme” sports has elevated SX from the sideshow days of mud bogs and tractor pulls to a point where it’s a prominent motorsport. In the past, there was little media attention. Now, SX is in print, on television and enjoying a growing presence on the internet. And while past champs like Bob “Hurricane” Hannah were well-known in racing circles, today’s heroes have their own TV commercials. Through all these changes, Team Honda was the one constant. Until now, that is.

Part of the fallout can be attributed to corporate downsizing and general attrition. In 1982, David Bailey signed his first Honda contract for $12,000, joining a huge, nine-rider team. Last December, Jeremy McGrath-Honda’s main man since Instead, McGrath changed brands just before the ’97 kickoff, leaving Honda to rely on defending 125cc MX champ Steve Lamson in the 250cc class. When Lamson and I25cc factory rookie Scott Sheak succumbed to injuries part way through the SX season, team manager Wess McCoy was left in the embarrassing situation of having a brand-new 18-wheeler with no one in it.

’93-was offered a deal reportedly worth $800,000 that would have made him the team’s sole full-time 250cc rider. When he turned it down, Honda’s reign effectively ended.

“It was never a matter of the way the team treated me or the equipment or anything,” explained McGrath, who now rides a Suzuki. “The company put too many restrictions on me and my personal freedoms. I just want to be happy and be able to live my life like I always have. It’s worked pretty good until then, so why change?”

“The objective for Honda has always been to win races, build good product and a good image, and further our development,” said McCoy, “and that didn’t change when Jeremy left. We have not diverted, even though we lost the captain of our team at the 11th hour. We relied so heavily on him that it devastated our ability to move forward in the 250cc class. How do you replace someone like Jeremy McGrath?”

When McCoy replaced long-time team manager Dave Arnold prior to the ’95 racing season, the former inherited a team that had won 11 of the last 13 SX championships and nearly threequarters of the races along the way. McGrath, Doug Henry and Lamson stayed, but others who helped build the program were either going or gone.

“After Dave Arnold left, Wess McCoy inherited a pretty damn good team,” said Honda of Troy boss Phil Alderton. “Arnold left, Roger DeCoster was long gone, J.C. Waterhouse quit the parts department, Jim Anderson (Showa) quit, Jeff Stanton retiredWess inherited the Honda legacy, but not the company personnel.”

Henry left in ’96, and McGrath would follow after adding two more SX crowns to the company’s treasure chest. (Only Lamson, with no supercross wins to his credit, remained.) Many blame McCoy for not being a better boss to McGrath, or at least a shield between the corporate brass and the racers.

“The problem is the guys who are dealing with the riders-the job that Dave Arnold was doing-are not taking care of the riders,” said DeCoster, now with Suzuki. “You cannot run racing like a corporation and treat top riders like they’re just doing some 9to-5 job. It’s hard to keep the balance between rules and flexibility, and they eventually became too strict. There has to be a liaison-a shock absorberbetween a company and its riders. That’s what Honda is lacking. It’s not the bike, the money or the riders.”

“When I was there, Honda was a family, my family,” explained Bailey, who now calls the races for ESPN. “Johnny O’Mara was my brother, Dave Arnold was an uncle, DeCoster was my dad. I never saw that between Jeremy and Wess McCoy.” Asked who he thought might have made a good replacement for McGrath, Bailey said, “That’s like asking the Chicago Bulls how they would replace Michael Jordan. You don’t. You keep him!”

How did Honda lose McGrath and go from a 14-race winner in ’96 to no wins in ’97? Pro Circuit’s Mitch Payton feels it was Honda’s own hubris that brought this sudden slide. “They’ve lost their focus,” he answered. “They’re so powerful and have such strong egos that they believe their own myths. They stuck to their guns when they were negotiating with Jeremy because they thought the bike was more important than the rider and Jeremy needed them more than they needed him. This isn’t IndyCar racing-this is supercross.”

Honda placed all of its bets on one horse this year-a horse that ended up in someone else’s stable. When McGrath bailed, the company had no talent pool to draw from. Whereas Kawasaki, Suzuki and Yamaha all have support or satellite teams as backup, Honda only had its affiliation with oft-injured Primal Impulse 125cc rider Robbie Reynard and Alderton’s Honda of Troy team. Moreover, the relationship with the latter became strained when Alderton bid for McGrath’s services.

“We started off in ’94 as a 125cc farm team, but we didn’t get the results that (Honda) expected. So they dropped that program, and we were on our own for ’95,” recalls Alderton. “At that point, we started concentrating on winning at the same level Honda was, and we have since hired some top guys (Larry Ward, Mike Craig, Mike Kiedrowski) to beat them. It’s an awkward situation, since we also helped McGrath through Suzuki of Troy when Honda didn’t. We’re trying to help Honda, but trying to beat them at the same time.”

“I’m not sure how we’re going to go about doing it, but we will rebound from our problems,” said the embattled McCoy. So, the sizzling rumor that Honda is going to pull the plug on its motocross team isn’t true? “No, hell no! We’ve already started to do the preliminary work, like checking the availability of certain riders and what they’re capable of. We haven’t been sitting around doing nothing. We’re breaking our asses, trying to get ready for the 125cc nationals and the 1998 season.”

Is there any chance of a reconciliation with McGrath, who took the ’97 SX title chase to the last round on a Suzuki? “That’s up to Jeremy,” McCoy said. “We would certainly entertain the thought. We’ve discussed it already with Jeremy. We’d be interested in talking to him again if he’s interested. But I don’t know how we can make him comfortable and happy again, because the contract he would get would be the same one he got this year. When the salaries are that high, there are certain things you have to give up. There was never a reason for Honda to chase Jeremy away. He left us.”

In ashes.

-Davey Coombs

Hines quickest ever

Second-generation drag racer Matt Hines rocketed to the quickest quarter-mile in NHRA Pro Stock history at the Mopar Parts Nationals in Englishtown, New Jersey. Hines, son of tuning legend Byron Hines, set the record in fourth-round eliminations against Angelle Seeling, firing his 260-horsepower Vance & Hines Suzuki GSX-R through the traps in 7.29 seconds at 183.37 mph.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Other Ten Best

August 1997 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Thousand Phone Calls

August 1997 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCPhilosophic Conversions

August 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1997 -

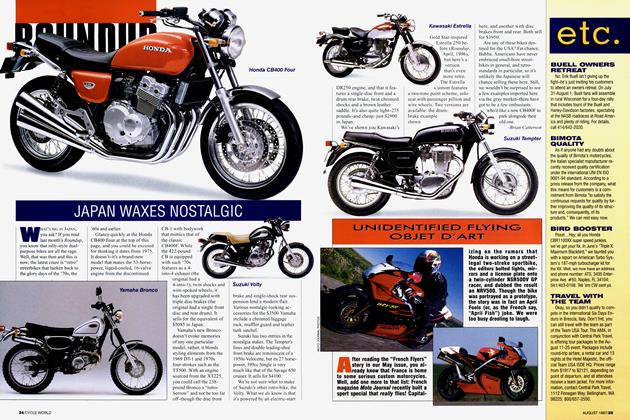

Roundup

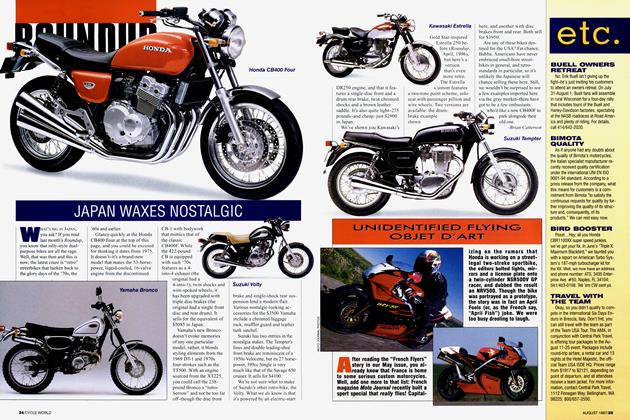

RoundupJapan Waxes Nostalgic

August 1997 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupUnidentified Flying Objet D'Art

August 1997